The Lyft Economy: it’s a Side Job

Driving around major U.S. cities, it seems like every other car has a Lyft or Uber logo in the back windshield.

Driving around major U.S. cities, it seems like every other car has a Lyft or Uber logo in the back windshield.

These ride-sharing apps are prominent players in the increasingly popular “platform economy,” which links sellers with buyers of their goods and services, from used couches and basement junk to handymen and car rides. This is one corner of the fast-growing gig economy, which also includes freelancers and the self-employed.

But who takes on these jobs, are they long-term or short-term endeavors, and how reliant are participants on the income they generate through online platforms or apps?

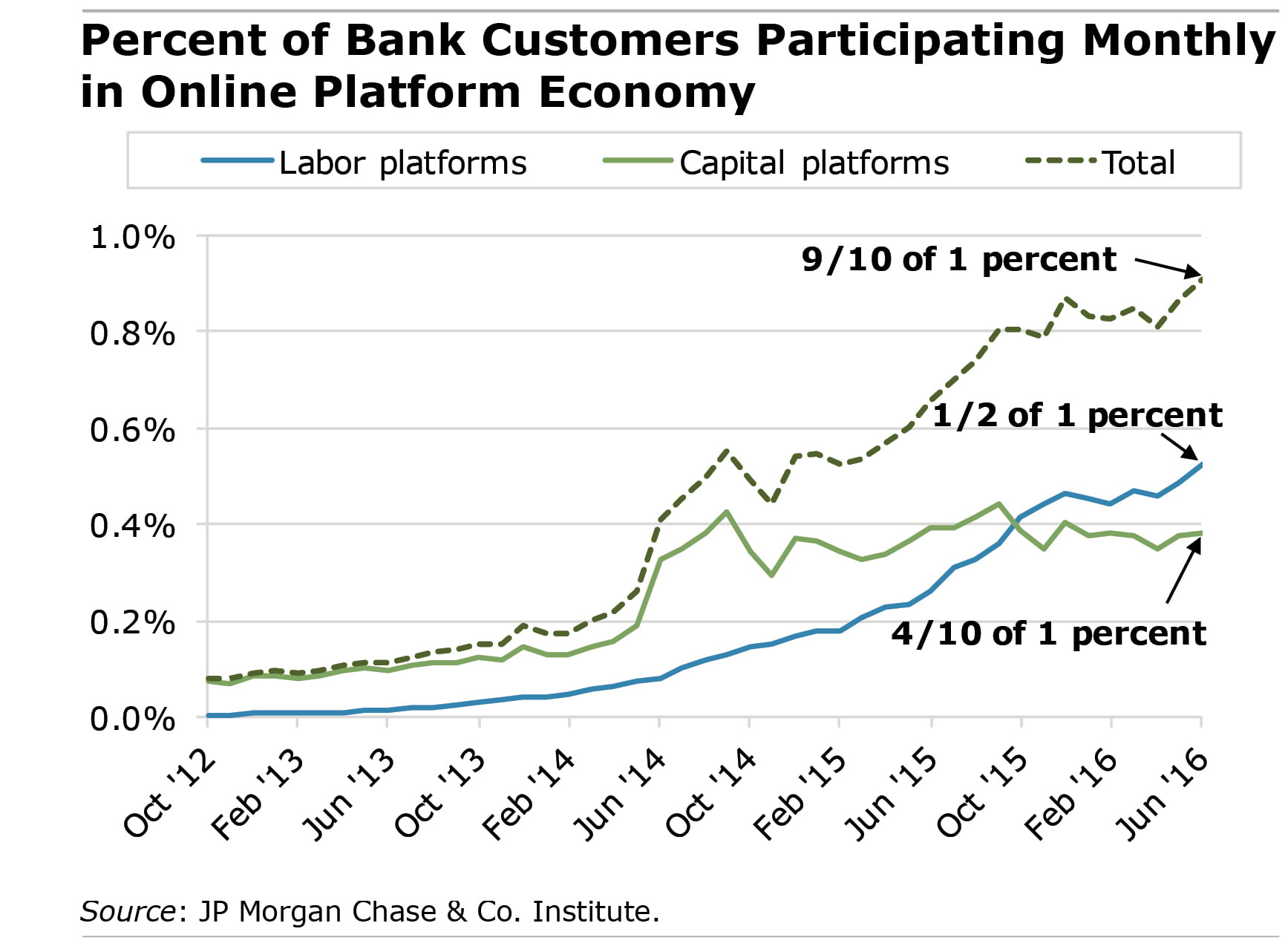

Scouring its database of transactions in the bank accounts of 240,000 bank customers who participate in the platform economy, the JP Morgan Chase & Co. Institute has put together a completely anonymous but interesting profile of the participants in this ever-present, but little-understood part of the economy.

Despite a proliferation in platforms, Fiona Greig, director of research at the JP Morgan Institute, said it’s fairly clear from these data this usually is not U.S. workers’ first choice for earning a living. Most people, “are not relying heavily on this,” she said. While users have to sell their wares on a piece-rate basis, “the flexibility that this offers makes for the perfect opportunity to add income.”

JP Morgan would not identify specific platforms that it tracks in its account database. But they are likely to include Uber and Lyft and the household helper website, TaskRabbit, where individuals sell their handyman, cleaning, or errand services – JP Morgan calls these “labor platforms.” Examples of “capital platforms,” where goods are sold, are Airbnb, eBay, and the fledging Darkroom.Tech, where photographers can sell prints of their work to social media fans.

In any given month, about 1 percent of the people studied use them to make some income, and more than 4 percent have used them at one time or another. Low-income workers and people who do not have steady employment are more likely to sell their services online. This also holds true, though to a lesser extent, for people selling goods.

The study observed the payments received in a customer’s bank account from 42 different platforms, which charge a transaction or subscription fee to act as the seller’s intermediary. So it didn’t include free platforms like Craigslist, where buyers and sellers transact offline.

Several findings in the study support Greig’s contention that the platform world is comprised mainly of part-time jobs.

- The platform economy is still growing. But the flow of new entrants has slowed in an era of near-full employment, and there is significant turnover – more than half of the people who try a platform leave within a year. When “a larger and larger proportion of participants have a traditional job, the opportunity cost of working on the platforms is now higher,” Greig said.

- This high rate of turnover “suggests that participants might not treat platforms like traditional jobs,” says JP Morgan’s report, “The Online Platform Economy: Has Growth Peaked?” “This might be because platforms as of yet do not typically offer the full package of income security, benefits, training, and income and career progress that many traditional jobs offer.”

- Established users typically generate only about one-quarter of their annual earnings this way – in other words, supplemental income. Lyft seemed to corroborate this, saying its data show that the vast majority of its drivers are on the road less than 20 hours per week.

“If these platforms start to offer what look like full-time jobs,” Greig said, “these opportunities could become competitive.”

After all, the only thing predictable about the online landscape is that it never stays the same. But how will future changes affect workers?

Squared Away writer Kim Blanton invites you to follow us on Twitter @SquaredAwayBC. To stay current on our blog, please join our free email list. You’ll receive just one email each week – with links to the two new posts for that week – when you sign up here.