Behind Asian-Americans’ Wealth Divide

When it comes to wealth, Asian-Americans aren’t much different than whites. The typical household’s net worth is around $133,000 in each group, and about 10 percent have no wealth at all.

When it comes to wealth, Asian-Americans aren’t much different than whites. The typical household’s net worth is around $133,000 in each group, and about 10 percent have no wealth at all.

And like white America, Asian-American inequality is high and rising. Asian-Americans ranking in the top 10 percent (in terms of their wealth levels) have $1.45 million in savings and home equity – about 170 times more than those in the bottom 20 percent. In the 1990s, the top 10 percent had 75 times more wealth.

Given this high concentration of wealth, “many Asian Americans, especially Asian American seniors who need to live off of their savings, live in an economically precarious situation,” according to a Center for American Progress study in December. The Urban Institute in a newer study concluded that “Asian American seniors are often left out of the national conversation on poverty.”

A deeper analysis reveals the dynamics at work in this rapidly growing and diverse socioeconomic group.

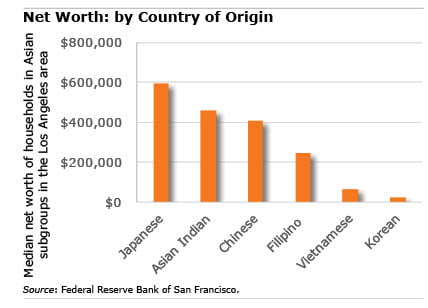

The timing of immigration is key to socioeconomic status. The Japanese, who came to this country in large numbers in the early 1900s, have had plenty of time to improve their lot. A new report by the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, focused on the Los Angeles area, found that people of Japanese descent are, by far, the wealthiest segment of the Asian community there. Remarkably, the median household’s net worth approached $600,000 in 2014.

Immigration from Korea, by contrast, didn’t pick up steam until the 1980s and 1990s. Not surprisingly, the typical Korean household lags behind, with about $25,000 in wealth. But that could be changing: one in five Koreans owns a business, the highest rate of business ownership for Asians in the Los Angeles area.

Inequality also emerges between generations in upwardly mobile Asian-American families.

In recent interviews at a Boston senior center, several elderly Chinese immigrants who had worked all their lives in low-wage restaurant or factory jobs proudly noted that their children attended college, fully aware this placed them a few rungs higher on the nation’s socioeconomic ladder. If their children didn’t make it to college, said Ruth Moy, founder of the Greater Boston Chinese Golden Age senior center, “the grandkids all go to college.”

“Nothing is universal, but education as a path toward greater prosperity and social prestige is pretty pervasive among Asian parents,” said Alex Pham, a Californian who emigrated with her parents from Vietnam as a child after the war, later earned two college degrees, and is now is now a content strategist for technology companies.

It is important not to always lump Americans into one big group when assessing their financial and retirement prospects. But even within the Asian-American community, this population’s diversity reveals more about the imbalance between its haves and have-nots.

In other recent blogs, Squared Away focused on the unique financial challenges facing the nation’s African-American and Hispanic communities.

Squared Away writer Kim Blanton invites you to follow us on Twitter @SquaredAwayBC. To stay current on our blog, please join our free email list. You’ll receive just one email each week – with links to the two new posts for that week – when you sign up here.

Comments are closed.

Putting Asian Americans in a single bucket, or even by country of origin fails to capture important sources of inequality. Chinese immigrants may be undocumented, may be highly educated STEM workers, or wealthy entrepreneurs. The latter groups may be yearning to be free, but are not the huddled masses of folklore. One suspects that economic status in country or origin is strongly predictive of economic status here.

Very true and valid points. Much harder to measure than simply grabbing available statistics.

I think there’s a risk whenever you view a metric (net worth) through the lens of a single factor. If you did a regression analysis, you’d probably see this factor as less significant than some others (and as is the case with this one, a proxy for how long someone has been in the country).

this is very good info

I was shocked by the statistics. In fact, although most of the Chinese recent years came here illegally and ended up undocumented or is working on the asylum, most of them who got green cards/ citizenship, they either do not earn much, or they do not file taxes up to the middle class level. So the data shown here looks biased towards those rich Chinese people.