High Fees Tied to Mutual Fund Complexity

When David Marotta is investing his clients’ money in mutual funds, he scrutinizes the fees.

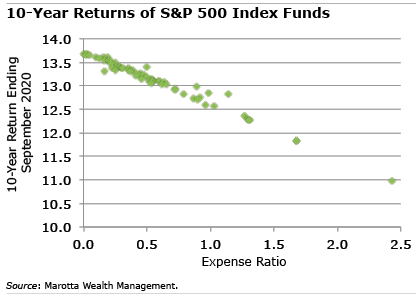

To demonstrate why fees are so important, Marotta charted the fees and 10-year returns for dozens of index funds in the Standard & Poor’s 500 family. Since these funds all track the same index and their performance is roughly the same, the fees will largely determine how much of the return the investor keeps and how much goes to the mutual fund company.

To demonstrate why fees are so important, Marotta charted the fees and 10-year returns for dozens of index funds in the Standard & Poor’s 500 family. Since these funds all track the same index and their performance is roughly the same, the fees will largely determine how much of the return the investor keeps and how much goes to the mutual fund company.

“The larger the fee the less that it performs. It’s kind of a straight line,” said the Charlottesville, Virginia investment manager. “Anytime we’re picking a fund” for a client, “we’re trying to find the lowest-cost fund that we can find in that sector.”

The fees for the S&P 500 index funds he analyzed using Morningstar data ranged from one-tenth of a percent to 2.5 percent of the invested assets.

The issue of fees versus performance is more complicated for actively managed investments, which sometimes have strong returns that justify paying a higher fee. But in any investment, the true measure of how it’s doing is the after-fee return.

However, deciphering mutual fund fee disclosures can be extremely difficult for do-it-yourself 401(k) and IRA investors – and that is by design.

An analysis of S&P 500 index funds identified numerous narrative techniques in mutual fund documents that confuse investors. The researchers – from the University of Washington, MIT, and The Wharton School – evaluated each fund’s disclosures and showed that funds with more complex explanations of their investment holdings and fees also have higher fees. The researchers call this “strategic obfuscation.”

The study, which covered the period from 1994 through 2017, illustrated this complexity with two firms’ descriptions of their S&P 500 index funds. Schwab’s one-sentence summary gets right to the point: “The fund’s goal is to track the total return of the S&P 500 index.” This fund’s annual fee is 0.02 percent of the assets.

Deutsche Bank’s disclosure is more complicated for a few different reasons. First, the summary is three paragraphs and starts this way: “The fund seeks to provide investment results that, before expenses, correspond to the total return of common stocks…”

Another way investment companies make it difficult to assess fees is by charging different fees for different “classes” of funds that hold identical investments – some are sold exclusively to institutional investors and some to individuals. Deutsche Bank’s S&P 500 index fund, for example, has several share classes. The fees are also reduced for people who invest more money. The fund’s complexity is reflected in the 2.3 percent fee for the least expensive Deutsche Bank S&P 500 fund available to individual investors – quite a bit more than Schwab’s – according to the study.

Investors also find that it’s tricky to sort out the differences between the various types of fees. The standard fee is the expense ratio, which covers an investment firm’s operating costs. Expense ratios have fallen dramatically in recent years, and the average last year was 0.45 percent – or less than one-half of 1 percent.

But many funds also have load fees – one-time charges for buying or selling funds. Load fees aren’t always easy to find in the fund disclosures but can significantly increase the cost of investing. Another confusing fee is the 12b-1 fee, which covers the company’s cost of marketing funds to investors. Under SEC rules, a fund can’t advertise itself as “no load” if its 12b-1 exceeds 0.25 percent of the investment assets.

The researchers argue that the connection between complexity and high fees, which can cut into performance, partly explains why people often make poor choices when investing their retirement savings.

Mutual fund companies use “both narrative and structural complexity to obfuscate high fees,” the researchers said.

Squared Away writer Kim Blanton invites you to follow us on Twitter @SquaredAwayBC. To stay current on our blog, please join our free email list. You’ll receive just one email each week – with links to the two new posts for that week – when you sign up here. This blog is supported by the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College

Comments are closed.

“The researchers argue that the connection between complexity and high fees, which can cut into performance, partly explains why people often make poor choices when investing their retirement savings.” The poor choice would be engaging a corrupt financial adviser. I doubt that Deutsche Bank markets its funds through magazine ads. They’re relying on advisers interested in fleecing their clients.

Fees should be shown as on a bank statement. Here was your beginning balance, here is the gain or loss of the underlying investments, here is what we charged you in fees, and of course… your ending balance.

Fees are not the only variable funds try to obfuscate. They also try to make it difficult to compare proxy votes.

When the SEC mandated that all funds report their proxy votes annually, there was an expectation they would do so in a uniform format so investors could compare them. Funds banded together and fought that.

The result is that all votes are reported on form N-PX in a way that makes them useful to no one, unless you are willing to pay thousands of dollars to subscribe to a service that extracts all that information and compiles it to enable such comparisons. The typical person has no such access, so often ends up with a fund that votes in ways that are not aligned with the investors values.

Understanding fees and the impact they have on returns to an investor is critical to success.

Anyone who invests should develop a solid understanding around fees. FINRA has a really powerful tool called the FINRA Fund Analyzer at: tools.finra.org. Anyone can get familiar with this tool and it has a powerful search feature for mutual funds including separate accounts for variable products, life and annuity. One can also add wrap fees for more complex analysis or relationships.

Most advisers are sensitive to fees and will openly address these with clients or prospects. Nobody wants headaches down the road.

“…actively managed investments, which sometimes have strong returns that justify paying a higher fee.”

How do you quantify “sometimes”?

When is this true? 1%, 3% of the time? I think this is a rare event for an actively managed investments to outperform, after fees, the S&P 500 ROI.