Inside the Minds of Older Workers

A decade of research into the impact of cognitive aging shows that workers throughout their 50s and 60s are generally just as productive as the younger people working alongside them.

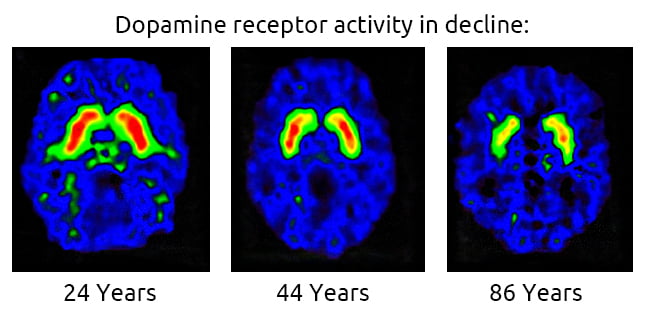

A new summary of this research, by the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College, explains how older people are able to adapt to the gradual loss of brain mass in the parts of the brain associated with memory and an ability to think on one’s feet – their “fluid intelligence.”

The highly skilled pharmacy profession is a good example of how workers in their 50s or 60s adjust to this changing dynamic. These pharmacists have an advantage over their younger coworkers in what psychologists call “crystallized intelligence,” which is the deep reserve of information stored up over decades of working in their profession. They can no longer process drug interactions and other new information as rapidly as they once did. But they can tap into their reserves to solve the myriad issues that crop up in their work. This crystallized intelligence – for pharmacists and many other types of skilled jobs – is effectively making up for their loss of fluid intelligence.

Interestingly, older workers who execute routine tasks usually aren’t at risk of aging out of their jobs for cognitive reasons either. That’s because even though their fluid intelligence is in decline, they have more than enough of it in reserve to complete their relatively simple tasks.

While the majority of older workers do not lose their productivity due to cognitive aging, two groups are vulnerable. One group is those for whom the work demands on their fluid intelligence are extremely high. A 2009 study of air traffic controllers highlighted this challenge – and demonstrates the logic behind a Federal Aviation Authority requirement that controllers retire at age 56.

That study used a simulation game to compare the amount of time it took to re-route two airplanes that were on a collision course. It compared the performance of young traffic controllers, old traffic controllers, young adults who are not controllers, and old non-controllers. The best performance came from the young controllers, who successfully rerouted the planes and averted a crash in six seconds. While the oldest controllers had years of experience, this could not make up for the decline in their fluid intelligence, which is critical to making fast decisions in life-threatening situations. They were no faster than young non-controllers – both took 10 seconds to avert disaster. (Of course, older non-controllers took the longest, 20 seconds.)

A second vulnerable group is the people who in time develop severe cognitive impairment. Acute dementia, in the form of Alzheimer’s disease, affects 15 percent of people between the ages of 65 and 74. Their cognitive impairment, which often begins in their early 60s, affects judgment and reasoning.

But these two groups are in the minority. Working longer is a very effective way to improve one’s retirement finances, and most older people can do it.

Squared Away writer Kim Blanton invites you to follow us on Twitter @SquaredAwayBC. To stay current on our Squared Away blog, please join our free email list. You’ll receive just one email each week – with links to the two new posts for that week – when you sign up here.

Comments are closed.

Hello Kim. A question: Is the 15 percent cited as having acute dementia limited to Alzheimers, or does it include all people with some form of acute dementia?

The 15 percent is limited to Alzheimer’s, which represents between 60 and 80 percent of all dementia cases. Vascular dementia accounts for another 10 percent, but the onset of such dementia is sudden, rather than progressive, and many people recover.