Retirees Who Tested Well Added More Debt

A new study finds that debt burdens have grown for older workers and retirees in recent decades. But this isn’t the first research to reach that conclusion.

What is new is whose debt burden is increasing the most: the people who score higher on simple memory and math tests.

Across the three age groups the researchers examined – 56-61, 62-67, and 68-73 – the high scorers on the cognitive tests were more likely to have debts exceeding half of their assets in 2014 than the high scorers who were the same ages back in 1998.

They also added disproportionately more mortgage debt than people with lower cognition during the study’s time frame, a period when house prices were rising.

The upshot of this study is that people who have retained more of their memory and facility with numbers are “more financially fragile” than the high scorers were in the past, the University of Southern California researchers said.

The findings run counter to a common belief that financial companies in recent years have had more success selling their increasingly complex products to unwitting borrowers – a belief perhaps fostered by the subprime mortgages targeted to risky borrowers in the mid-2000s that triggered the global financial collapse.

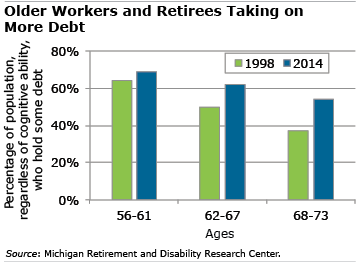

The share of the older people in the study who were carrying debt increased between 1998 and 2014 regardless of their cognitive ability. The biggest jump occurred after 62 – a popular retirement age pegged to Social Security eligibility.

The share of the older people in the study who were carrying debt increased between 1998 and 2014 regardless of their cognitive ability. The biggest jump occurred after 62 – a popular retirement age pegged to Social Security eligibility.

The heart of the analysis, however, is exploring the connection between cognitive ability and financial vulnerability. The researchers found the opposite of what one might expect: debt problems have loomed larger over time for those with higher scores on survey questions testing word recall and cognitive ability using simple subtraction and backward-counting exercises.

One way to explain this finding is that older people with higher cognitive ability may be more confident of their financial decisions, which could make them more likely to take risks – including a willingness to embrace more debt.

To read this study, authored by Marco Angrisani, Jeremy Burke, and Arie Kapteyn, see “Cognitive Ability, Cognitive Aging and Debt Accumulation.”

The research reported herein was derived in whole or in part from research activities performed pursuant to a grant from the U.S. Social Security Administration (SSA) funded as part of the Retirement and Disability Research Consortium. The opinions and conclusions expressed are solely those of the authors and do not represent the opinions or policy of SSA, any agency of the federal government, or Boston College. Neither the United States Government nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, make any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of the contents of this report. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise does not necessarily constitute or imply endorsement, recommendation or favoring by the United States Government or any agency thereof.

Comments are closed.

You had an article about whether or not to pay off a mortgage before retirement. One retiree called the low interest rates “free money”. That might be an influence. After all, recent retirees have lived through the inflationary 70s. Locking in low interest rates with debt may seem low risk to those who’ve seen much higher rates. If the debt is used to secure a house, I would say we’ve all been trained to think that “good debt”. I’ll also speculate that today’s retirees don’t seem to be willing to live in the small houses that our grandparents did when they retired.