Why are Consumers So Glum? Inflation and High Rates

The recession that economists predicted has never materialized. Unemployment has been under 4 percent for more than two years, a low more characteristic of the go-go 1960s than modern times.

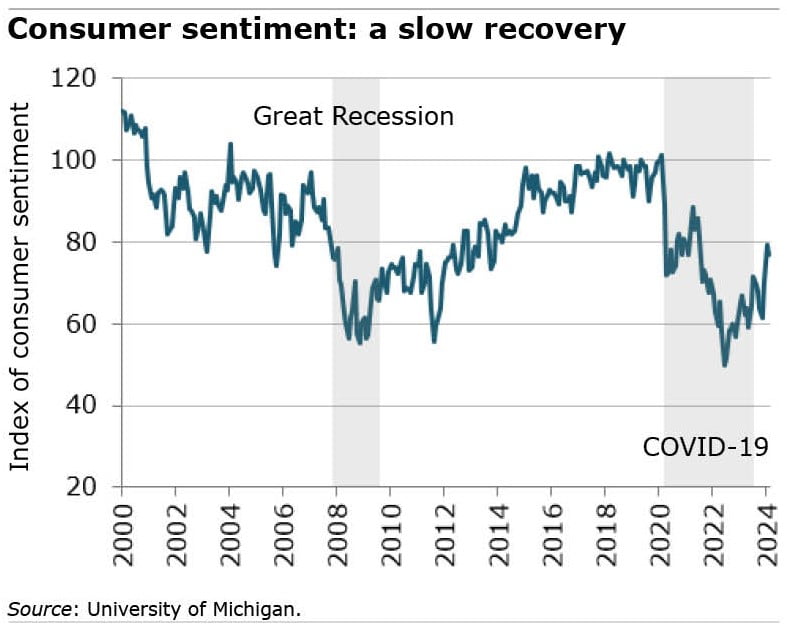

But although consumer sentiment, as measured by the University of Michigan’s monthly survey, is improving, it is still mired in the same territory that it was after the 2008 financial crisis.

The first reason is, of course, fallout from COVID-fueled inflation. Americans continue to feel the pain of paying more for everything from eggs and consumer goods to cars.

But inflation began to ease up last year and remains well below the pandemic’s 9 percent peak, despite March’s unwelcome increase of 3.5 percent annually. So how to explain consumers’ sour mood? What else might be missing from our understanding of what is driving their views of the economy.

A new study has an answer: high interest rates. The researchers make the case that consumer sentiment reflects not just inflation but also the current high interest rates on car loans, mortgages and credit cards that followed the Federal Reserve’s attempt to rein in inflation by raising the federal funds rate last year.

If high interest rates were included in a revised Consumer Price Index (CPI), a new reality comes into the picture that more closely tracks how unhappy people are feeling. “Consumers are considering the cost of money” – interest rates – “in their perspective on their economic well-being,” said the researchers, who include former U.S. Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers.

One example of how high interest rates affect consumer sentiment is homebuying. House prices have increased about 40 percent since the pandemic but mortgage rates have more than doubled. When a couple is house shopping, the rate – and not just the property price – determine how much the mortgage payment will take out of their paychecks.

The cost of financing a new car or truck is no small matter either when interest is added to the much higher post-pandemic vehicle prices. Credit card rates have also increased, from 15 percent two years ago to 21 percent last year, according to the study.

Last summer, the Federal Reserve paused its interest rate increases. March’s unencouraging report will likely extend that pause rather than provide the Fed with justification for cutting rates.

Whether inflation picks up or cools down will determine the Fed’s next move – and consumers’ mood in an election year.

Squared Away writer Kim Blanton invites you to follow us @SquaredAwayBC on X, formerly known as Twitter. To stay current on our blog, join our free email list. You’ll receive just one email each week – with links to the two new posts for that week – when you sign up here. This blog is supported by the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.