Will Washington State’s Long-term Care Program Survive a Ballot Initiative?

Developing countries all over the world are struggling with the same looming crisis: an aging population and an acute and worsening shortage of family and paid caregivers.

Washington State did something about it. The question now is, will its new program to fund services for seniors survive a ballot initiative that would undermine it?

In 2019, state lawmakers approved a Social Security-style insurance system requiring employees to contribute 58 cents for every $100 they earn to the WA Cares Fund. But instead of retirement benefits in old age, they will be eligible for $36,500 to subsidize some of their costs for services like home health aides, wheelchairs, assisted living, or even to pay an hourly wage to a family caregiver. People who move out of Washington State can still collect the benefits they’ve earned.

The long-term care program “is the third pillar of retirement security” along with Social Security and Medicare, Ben Veghte, director of the WA Cares Fund, said in an interview.

But the program is under attack for being a largely mandatory program. (Self-employed workers are exempt but are allowed to participate.) Opponents put an initiative on the November ballot that would make WA Cares voluntary for employees, which retirement experts said would doom the program, creating a death spiral as people opposed to the payroll deductions pull out and undermine its fiscal stability.

More than a decade ago, the voluntary nature of a similar federal long-term care insurance program, the CLASS Act, forced the Obama administration to scrap it. The administration determined that the voluntary program, which would have paid for services that allow older Americans to remain in their homes, was unsustainable.

But caring for the nation’s aging population is increasingly urgent. An estimated 80 percent of Americans will use at least some long-term care services in old age, according to a 2021 study. But there is a big shortfall between the services they will need and what many will be able to afford.

Only one in three 65-year-olds today has enough family and financial resources to cover even a minimal amount of care, and only one in five will be able to afford adequate care if they develop the most severe illnesses or disabilities as they age.

California healthcare advocate Bonnie Burns is concerned Washington’s program may not survive the ballot initiative because it is so challenging to convince younger workers to recognize the need for a service – long-term care – that they won’t use for decades in the future.

WA Cares, like Social Security, is a social insurance program that requires regular contributions so they build up over many years to ensure funds are available in retirement. People don’t want to “pay premiums until they think it’s going to affect them – and that is usually at later ages,” Burns said. At that point, “the cost goes up tremendously.”

The WA Cares Fund began collecting workers’ contributions from their employers in July 2023. The state estimates it will have built up at least $3 million by July 2026, when it will begin paying out benefits to subsidize older residents’ long-term care services and supports.

For the people who will need intensive services, Washington’s inflation-adjusted $36,500 benefit won’t go that far. But WA Cares administrators say it was designed primarily to provide seniors or their family caregivers with some support so they can remain in their homes or tide them over until the family can arrange a longer-term financial solution. Medicaid is the program of last resort for people with intensive needs who will require care over a long period of time but can’t afford it.

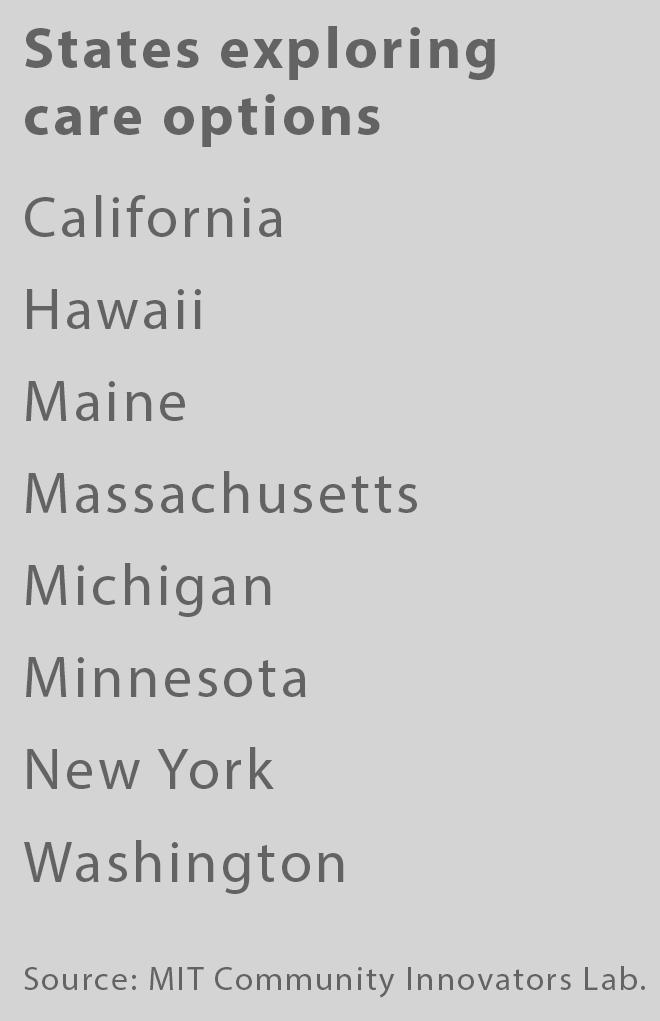

Washington is the only state with a long-term care program, and it attempts to tackle a problem that pervades the developed world, where populations are aging and birth rates are declining. Several other states, recognizing the need for solutions, have conducted studies on similar insurance programs, including California, Massachusetts, and New York.

Care for the elderly is not just a burden on families. Veghte of WA Cares pointed out that it also is a drag on the state economy. Working people who care for an elderly spouse or parent – mostly women – “are typically obliged to reduce their labor market participation by cutting their hours or turning down promotions. It hurts employers because their employees can’t take on leadership roles, and it devastates their economic and retirement security,” he said.

“Regardless of what happens with WA Cares, the forces that made it necessary are not going away,” he said.

Squared Away writer Kim Blanton invites you to follow us @SquaredAwayBC on X, formerly known as Twitter. To stay current on our blog, join our free email list. You’ll receive just one email each week – with links to the two new posts for that week – when you sign up here. This blog is supported by the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.