Suburban ‘Rent Deserts’ are a Problem

Boston, a city of fewer than 1 million people, is surrounded by layers and layers of suburbs linked to the city by subways, ferries, and a commuter rail. The suburbs’ opposition to a new state law requiring them to zone some land for apartments illustrates why U.S. rental housing is scarce and rents have soared.

The sprawling town of Hamilton, with 8,000 residents, told The Boston Globe that rental housing will “destroy the well-being of our community.” Other municipalities warn their schools, infrastructure, and police and fire departments will be overwhelmed by population increases or that they don’t have enough land to accommodate multifamily rental properties.

Not all of Boston’s suburbs are opposed to building more multifamily housing. Before the state law passed, the city of Newton had already started revamping its zoning regulations to encourage more rental properties around transit stops. But three out of four of the 23,000 lots in Newton are currently zoned for single family homes.

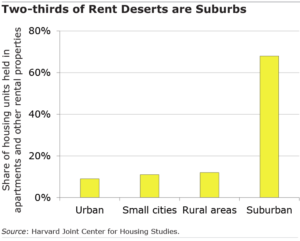

Suburban neighborhoods around the country account for more than two-thirds of “rental deserts,” according to a report by Harvard’s Joint Center for Housing Studies. The deserts are mostly white and mostly higher-income, and less than 20 percent of their housing stock is rentals, compared to a range of 50 percent to 80 percent in areas with ample rental properties. Low inventories nationwide have fueled double-digit rent increases from Idaho to Florida.

In the city of Boston, house prices have skyrocketed, so suburbs with mass transit are somewhat more affordable for lower- and middle-income workers who commute downtown to their jobs. But rental deserts, with their “not-in-my-backyard politics” are “a significant factor in limiting opportunities for rental households and for lower-income renters in particular,” the housing center said.

Massachusetts’ new law requires cities and towns to zone areas around public transportation for apartments. Still in question is whether the law will result in more affordable housing because deciding whether to build in these zones is still determined by the suburb and whether the tracts appeal to developers. Municipalities that do not comply with the zoning requirement will jeopardize state grants for utility and street improvements and amenities like bike paths.

Harvard points to Massachusetts’ and similar laws in a few states like California and Oregon as steps that could expand the rental options for workers.

But grumbling about the law by dozens of Boston’s suburbs also shows just how big a challenge building the badly needed rental housing will be.

Squared Away writer Kim Blanton invites you to follow us on Twitter @SquaredAwayBC. To stay current on our blog, please join our free email list. You’ll receive just one email each week – with links to the two new posts for that week – when you sign up here. This blog is supported by the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Comments are closed.

Zoning restrictions aren’t a bug. They are a feature designed to keep out dark skinned types who pay little property tax and have kids needing education. If you want to change behavior, you need to change the incentives.

Most people who live in suburbs moved there, usually at great expense, because they chose to live in a less densely populated environment. Understandably, they don’t want the character of their neighborhood to change to a crowded, more city atmosphere that isn’t what they chose to purchase. The additional buildings and their occupants will also put additional strain on municipal services such as schools, fire department, and police, causing taxes to rise and usually, service to decline. It’s a natural reaction to want things to stay the same.

All they have to do is allow homeowners living in their homes — actually present on the property — to have accessory dwelling units. The problem with the suburbs is there is too much housing — a house that had five people now has two, or one.

So, add a second unit. Generally there are enough bathrooms that all it takes is a kitchen and separate entrance.

And then in a family with children buys the home, convert it back to a one-family.

As noted, one family zoning was initially snob/racist zoning, but the snobs and racists ended up pricing out their own children. Just another self centered policy by Generation Greed. And a greenwashed one — the worst of it happened after th 1970s, on “environmental” grounds.

Many people moved out of town because they wanted to live in less populated areas. Additional buildings and their residents will put an additional burden on municipal services, such as schools, police, and fire departments. This will result in higher taxes and, as a result, lower quality services.