This Investment Is Cheaper and Better than Mutual Funds

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Opponents shouldn’t block 403(b)s from purchasing collective investment trusts.

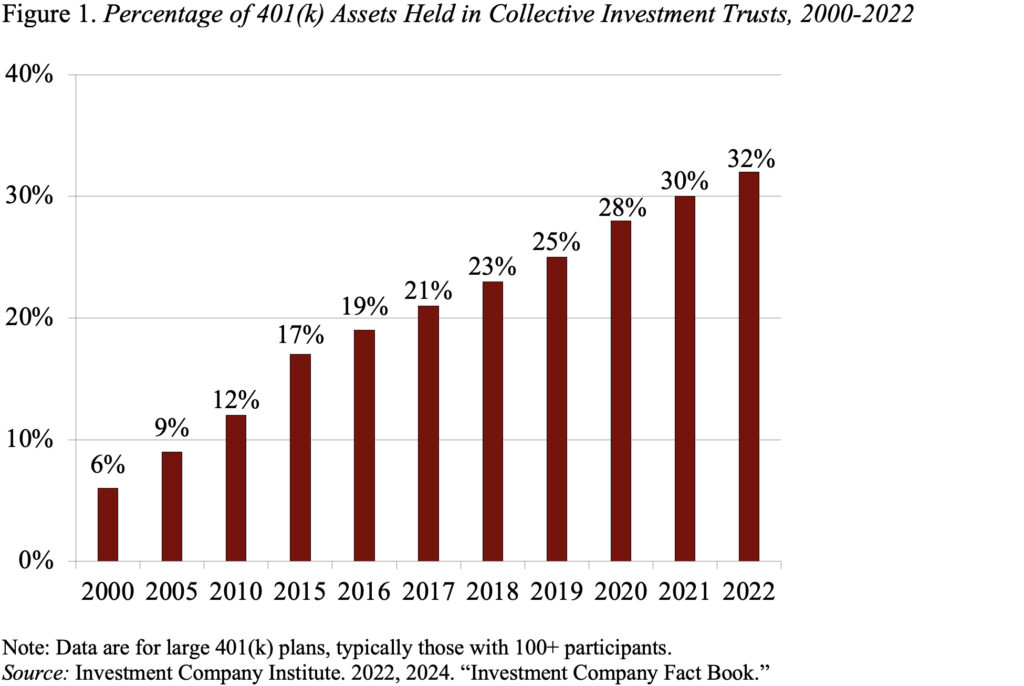

Anyone concerned about fees in retirement plans should be delighted that the use of collective investment trusts (CITs) that invest in the same assets as mutual funds has been increasing among 401(k) plans (see Figure 1) and that the SECURE 2.0 legislation allows 403(b) plans to invest in CITs. (403(b) plans are retirement savings plans sponsored by public educational institutions, 501(c)(3) tax-exempt organizations, and other non-profits.)

Unfortunately, a group of organizations wants to block CITs from 403(b)s. (For you lawyerly types, while SECURE 2.0 amended the Internal Revenue Code to allow 403(b) investment in CITs, the securities laws also need to be amended. Such an amendment appears in Section 205 of the Empowering Main Street in America Act of 2024, which is currently under consideration by the Senate.)

My sense is that no one disagrees that CITs cost less than mutual funds for the exact same bundle of securities. My friend Francis Vitagliano made me take a closer look at this issue about two years ago. His contention was that 401(k) plans were paying mutual funds about $1 billion in transfer agent fees for services they already receive through their recordkeeper.

How could that happen? Here’s what 401(k) recordkeepers do for plans:

- Maintain individual accounts – accept contributions and process withdrawals.

- Calculate and report the balance in each participant’s account daily.

- Facilitate required plan disclosures, such as on Form 5500.

- Maintain website and perform all types of participant communications.

Transfer agent tasks for individual investors at mutual funds involve functions #1 and #2 above – maintaining the account and calculating the daily balance. Since 401(k) plans have one omnibus account at each mutual fund company, the transfer agent performs functions #1 and #2 for the plan as a whole, while all the processing for individual participants is done by the 401(k)’s recordkeeper. At the time, my estimate was that mutual funds were overpaying $2 billion in transfer agent fees – higher than Francis’ number! CITs pay none of the redundant transfer agent fees.

CITs are also cheaper than mutual funds because – being sold only to retirement plans and other sophisticated investors – they are not required to register under the federal securities laws and thereby avoid many of the regulatory costs associated with products offered to the general public.

CITs’ status under the securities laws does not mean that they are “unregistered financial products,” as claimed by opponents. CITs are maintained by banks and therefore are subject to banking regulations governing CIT trustees. They are also subject to common law principles of fiduciary duty.

More interesting, if a retirement plan covered by ERISA invests in a CIT, the manager of the CIT is subject to ERISA fiduciary obligations. In other words, as long as one of the investors in the CIT is an ERISA plan, all the CIT assets will be managed in accordance with the ERISA fiduciary standard. That means that if a 403(b) plan not covered by ERISA (such as those for public school teachers) invested in a CIT, that portion of the plan’s assets would benefit from ERISA protections. In short, CITs not only lower investment costs for retirement saving, but also can spread ERISA’s fiduciary protections to uncovered plans. Opponents simply have no case for trying to block 403(b)s from purchasing CIT assets. In fact, maybe we should also open up IRAs to CITs as a way to get ERISA protections for at least some of the assets in those high-fee arrangements.