Lowering Pay for Federal Jobs Is Bad for Workers – and Bad for America

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Going forward, the government will have to pay more – not less – to be competitive.

A suggested revenue proposal that was initially included in Trump’s “one big beautiful bill” would increase the contribution that federal employees make to their defined benefit plan. Increasing the contribution rate might be a good idea if federal employees were overpaid relative to private sector workers and not so good if they earned less.

| The Specific Proposal: The federal government sponsors retirement benefits through the Federal Employees Retirement System (FERS), which is jointly funded by employees and their agencies. Employee contributions are counted as federal revenues. Participants hired before 2013 currently contribute 0.8 percent of their salary, those hired in 2013 contribute 3.1 percent, and those hired in 2014 or later contribute 4.4 percent. Under this proposal, all employees would contribute 4.4 percent. The increase in the contribution rates would be phased in and produce an estimated $35 billion in revenue over the period 2025-34. (Note: this proposal was eliminated before the bill passed the House, but could potentially come back in the Senate version or in the future.) |

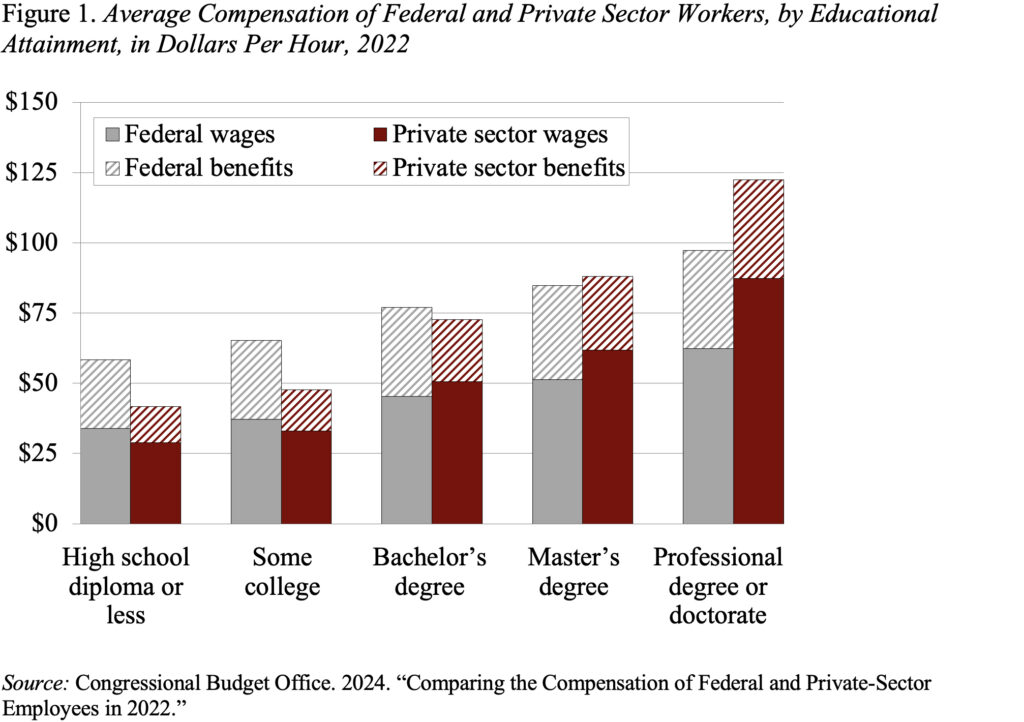

Total compensation consists of cash wages and fringe benefits, primarily health insurance and employer contributions to retirement plans. According to the Congressional Budget Office, for employees with a college degree or above, wages for federal employees are consistently less than those for private sector workers (see Figure 1). Benefits, however, are more generous for federal workers, which fully compensates for the low wages for those with a bachelor’s degree, but federal workers with higher degrees continue to fall short. In contrast, at lower levels of education federal workers earn more than their private sector counterparts.

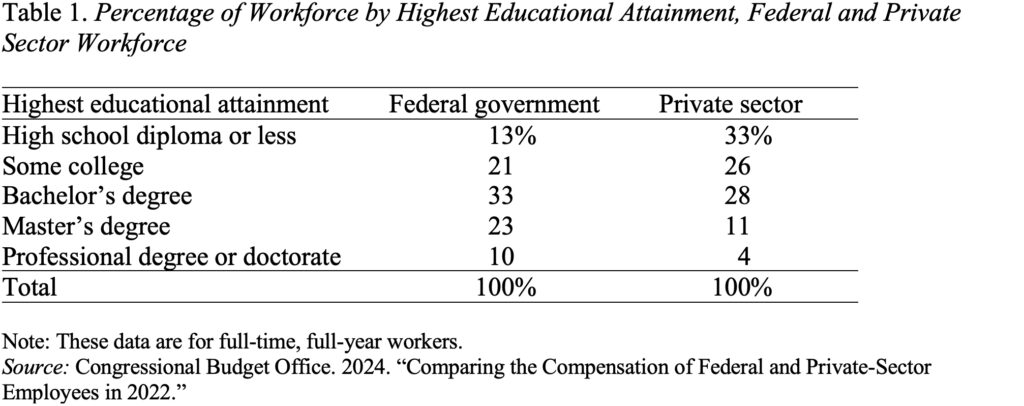

To understand how much weight to put on the various comparisons, it is important to know how many workers fall into the various education buckets in the federal government and the private sector. As shown in Table 1, two-thirds of federal workers have a bachelor’s degree or more, compared to 43 percent of private sector workers. That is, most federal workers earn lower wages than their private sector counterparts.

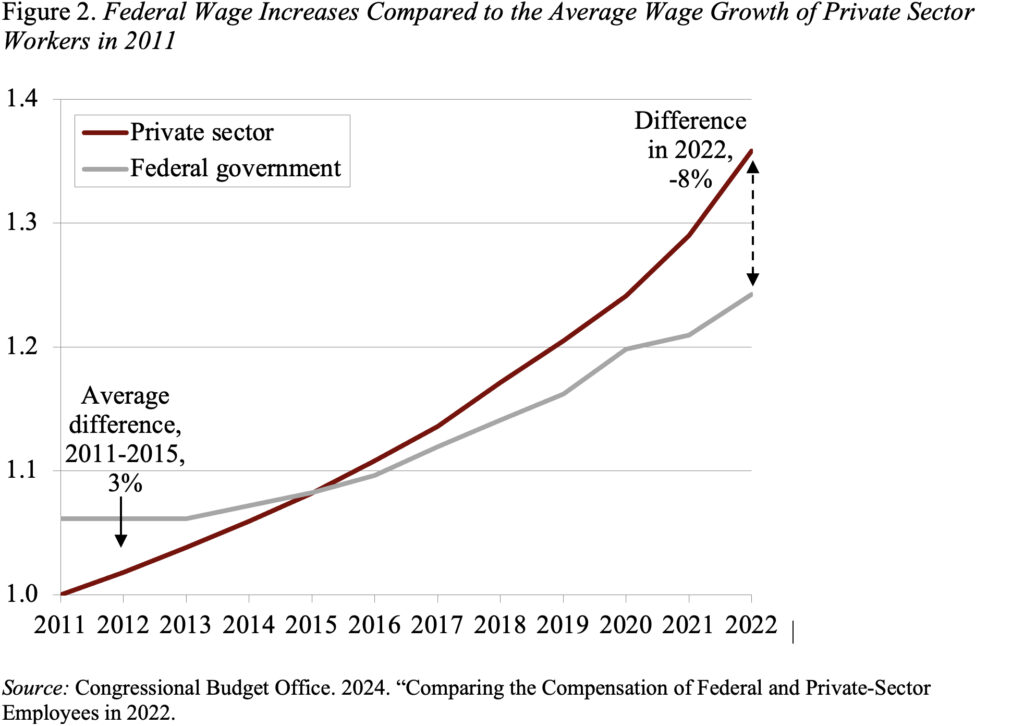

Moreover, the relative position of federal workers has deteriorated over time. Between 2011-2015 – the years for CBO’s last comparison – and 2022, the excess pay for federal workers with less education declined, and the shortfall in pay for federal workers with the most education increased. The relative decline in federal compensation reflected smaller across-the-board wage increases (see Figure 2), which also held down growth in the cost of pensions and other benefits closely tied to salaries.

Why, you might ask, would highly educated people be willing to work for less in government? The CBO offers several reasons – the most prominent of which is job security. “Workers value job security, and federal employment offers more of it than many jobs in the private sector.” Well, thanks to DOGE, that’s no longer true. As a result, to stay competitive the federal government will have to substantially up their compensation to workers with higher levels of education.

The bottom line is that any proposal to reduce the compensation across-the-board for federal employees is a move in the wrong direction.