How Do State Auto-IRAs Affect Adoption of Employer Plans?

The brief’s key findings are:

- To expand access to retirement saving, some states now require firms to offer their own plan or enroll their workers in a state auto-IRA program.

- As these programs were rolled out, one question that emerged is whether they would lead to fewer – or more – employer plans.

- Our results show that auto-IRAs have boosted the share of firms offering plans.

- Thus, auto-IRAs have expanded access in two ways: 1) through participation in auto-IRAs themselves; and 2) through increased adoption of employer plans.

Introduction

Employer-sponsored retirement plans – such as 401(k)s – offer a convenient way for workers to save through contributions deducted from their paycheck. Yet, many private sector workers lack access to an employer plan.1 In recent years, a number of states have aimed to give such workers a payroll-based savings option by requiring employers to either offer their own retirement plan or enroll their workers in a state-facilitated “auto-IRA” program. A state auto-IRA offers the convenience of payroll deductions, albeit with lower contribution limits than employer plans and no employer match.

As these programs were being developed and launched – with Oregon moving first in 2017 – one question that emerged was whether state auto-IRAs would impact employers’ decisions to offer retirement plans to workers. Auto-IRA program availability could prompt some employers to drop their own plans in favor of participating in the state programs. On the other hand, the reverse could happen – employers who did not previously offer their own plan might decide to adopt one instead of opting for the auto-IRA. This brief, based on a recent study, explores whether auto-IRAs have led to fewer – or more – employer plans.2

The brief proceeds as follows. The first section provides background on the state auto-IRA programs. The second section discusses the data and methodology used to determine how these programs have impacted the share of employers offering their own plans. The third section discusses the results. The final section concludes that state auto-IRAs have prompted more employers to offer their own retirement plans. Overall, then, the auto-IRA initiatives have given many additional workers the option to save via payroll deduction in two ways: through participation in the new auto-IRAs and through increased adoption of employer plans.

Background

Employer-sponsored retirement plans are the main source of retirement saving for individuals outside of Social Security and are a popular benefit offered by many employers. But only about half of private sector workers at any given point in time are participating in an employer plan. Many of these nonparticipants work for employers who do not offer a plan.

In 401(k)-type plans, workers make tax-preferred contributions, with their employer often matching a portion. The contributions are invested in an option chosen by the individual, although many people stick with the default chosen by their plan, which is often a target date fund. Workers without an employer plan can set up their own individual retirement account (IRA) to save, but very few do. Most IRA balances today represent rollovers from employer plans at a job switch or retirement.3

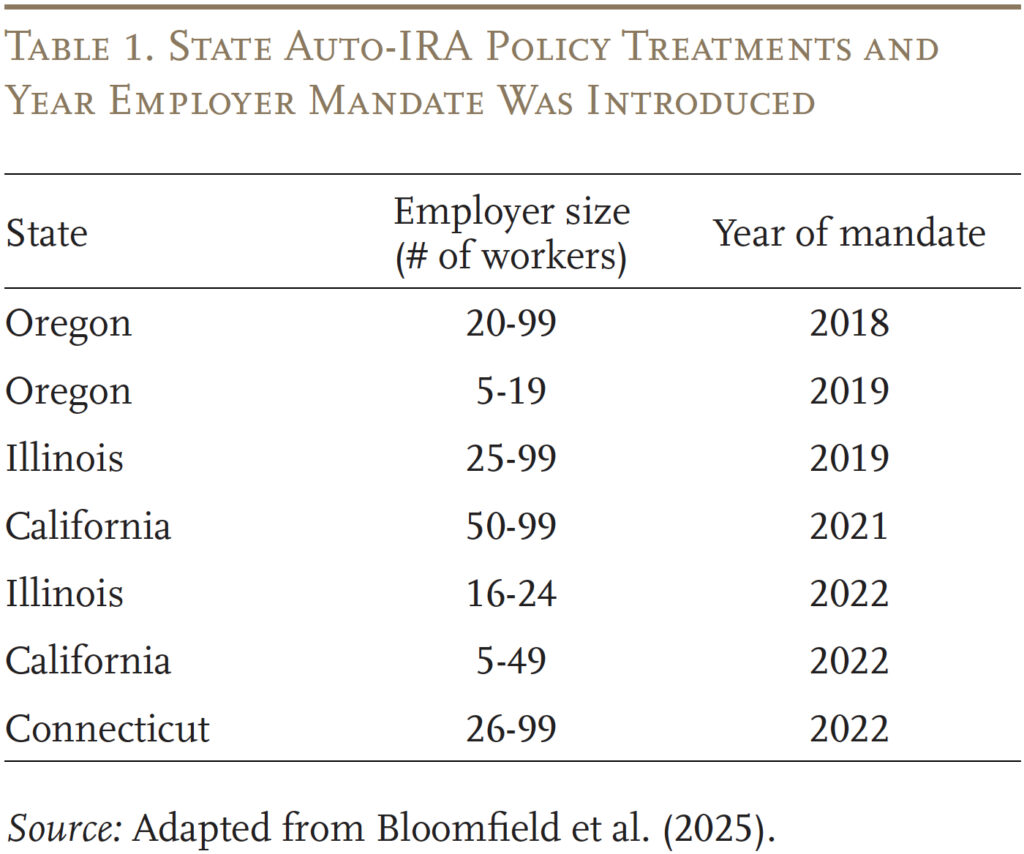

Policymakers at the state and federal levels have attempted to increase retirement plan coverage and participation. The federal government has aimed to incentivize employer plan formation, and states have adopted auto-IRA policies. The auto-IRA policies covered by our study were rolled out between 2017 and 2022 in Oregon, Illinois, California, and Connecticut (see Table 1).

Auto-IRA policies have two main features. First, the state contracts with a private sector financial services company to create Roths IRA accounts for the employees of participating firms. Firms that participate automatically enroll their workers and make the payroll deductions specified by the state (3 percent or 5 percent in the four states studied). By default, the assets are invested in a fund recommended by the plan manager and approved by the state administering the program – typically a target-date fund.4 Like 401(k) plans with auto-enrollment, the employee is free at any time to opt out of the auto-IRA, change their contribution amount, or change their investment fund to other options offered under the plan.

Second, employers must either participate in the state auto-IRA program or adopt their own retirement savings plan. States have applied these employer mandates on a rolling basis, starting with large firms and moving down to smaller ones, enforcing compliance with the possibility of financial penalties. The research summarized here focused on the introduction of seven such mandates, as shown in Table 1.5

Data and Methodology

To analyze the effect of state auto-IRAs on employer plans, this study uses administrative tax data to follow firms annually from 2012 to 2023. It starts with IRS Form 941, which is used to identify a firm’s state and the number of people it employs. However, this form does not include information on whether an employer offers a retirement plan. So, we use a firm’s Employer Identification Number to link each business to their employees’ W-2s. This linkage allows the study to use Box 12 on the W-2 (which includes retirement plan contributions) to see whether at least one of the firm’s employees contributes to an employer plan. The study considers such a contribution within a given year as evidence that the firm offered a plan.

With data on firms offering a plan in hand, the next step is to create a panel of “treated” and “control” firms for each of the seven policy changes relating to the state auto-IRA policies. Specifically, the analysis follows each firm starting from five years before their mandate up through 2023. Treated firms are in the indicated size range and located in the adopting state. Control firms are in the indicated size range, but from states that never adopted an auto-IRA policy.6

After constructing a panel for each policy change, we apply regression analysis to examine how the share of firms offering their own plan changed once a mandate came into effect.7 The regression estimates the post-policy changes in the shares of control and treatment firms offering a plan, compared to two years before the policy. The difference between these two changes gives us the causal effect of the policy.8

To illustrate, consider the following hypothetical example for Oregon firms with 20-99 employees, whose mandate came into effect in 2018. Suppose 30 percent of these firms offered a plan in 2016 (two years before the policy) and 36 percent in 2020 (two years after the policy). Thus, the share of treatment firms offering a plan increased by 6 percentage points two years after the policy. Suppose further that these numbers are 32 and 35 percent for control firms – representing a 3-percentage point increase over the same period. Our analysis assumes that, in the absence of the policy, firms in Oregon would look like these control firms; that is, their offer rate would increase by 3 percentage points between 2016 and 2020. Since Oregon firms increased their offer rate by 6 percentage points rather than 3 percentage points, we would estimate that the policy caused a 3-percentage-point increase in the offer rate in 2020 compared to 2016.

Results

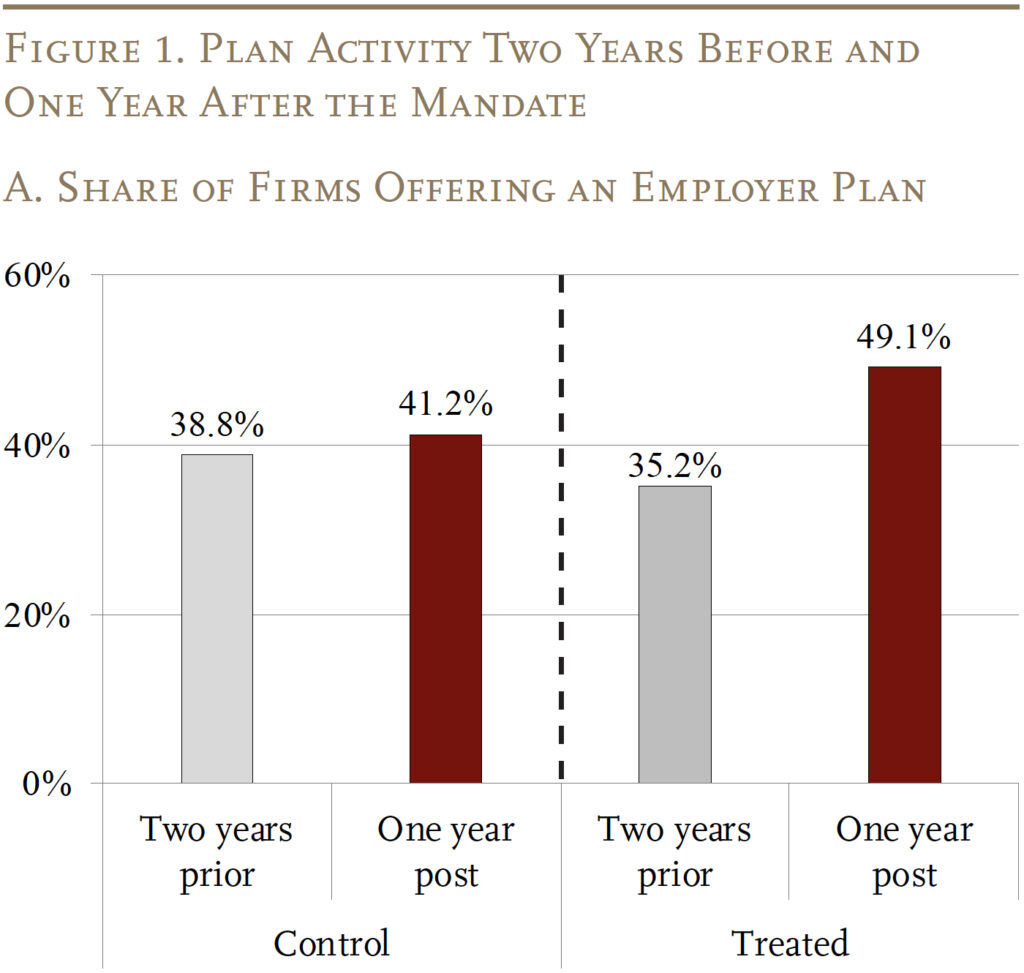

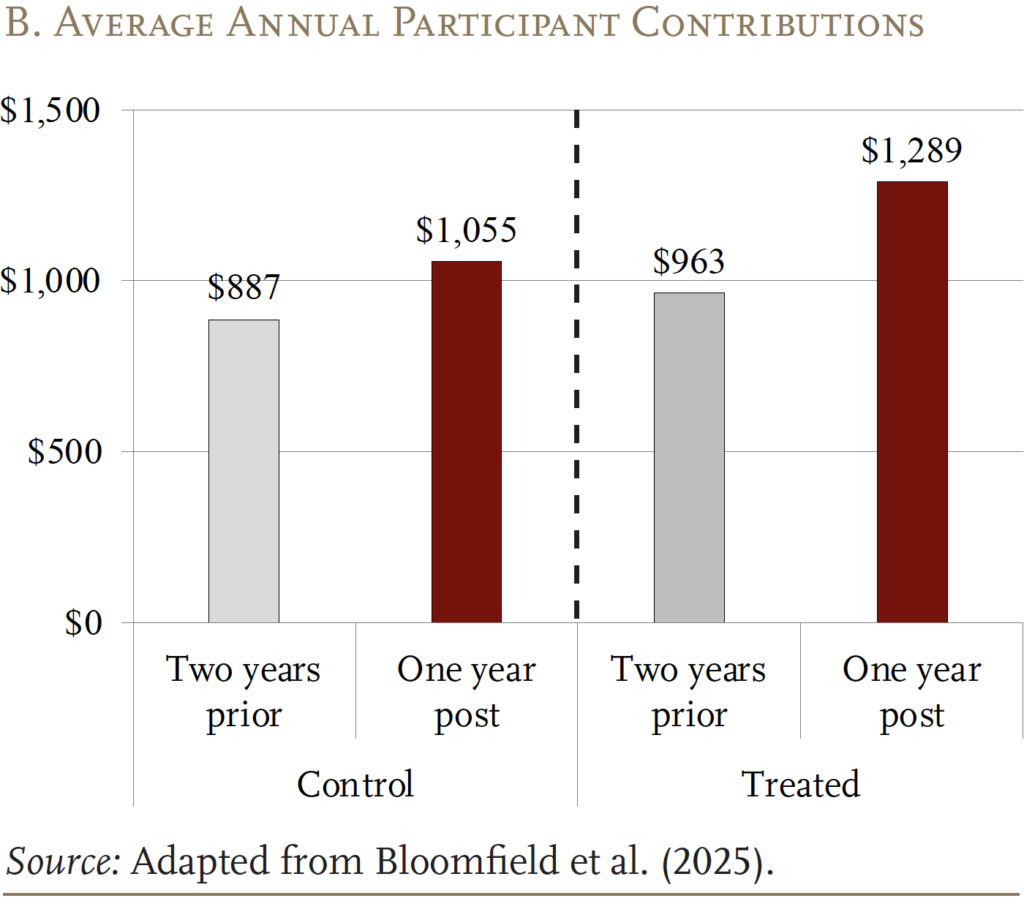

To start, Figure 1 provides some descriptive (i.e., non-regression-based) evidence that many firms in auto-IRA states adopted their own retirement plans. Figure 1A shows the shares of treated and control firms offering any plan before and after the policy change. Figure 1B shows the amount those firms’ employees contributed to the plans. The share of control firms offering a plan grew 5 percent, while the share of treated firms offering a plan grew by 40 percent. Employee contributions also grew faster in the treated firms.

While Figure 1 suggests the auto-IRA policies may be encouraging more adoption of employer plans, it combines firms of very different sizes that were treated on different dates. For example, California firms with 50-99 employees are included for 2019 (two years before the policy) and 2022 (one year after the policy). Ideally, we would compare these firms to similar-size firms in non-treated states during the same years. However, because Figure 1 lumps all control firms together, the California firms are also being compared to firms of different sizes and different years.

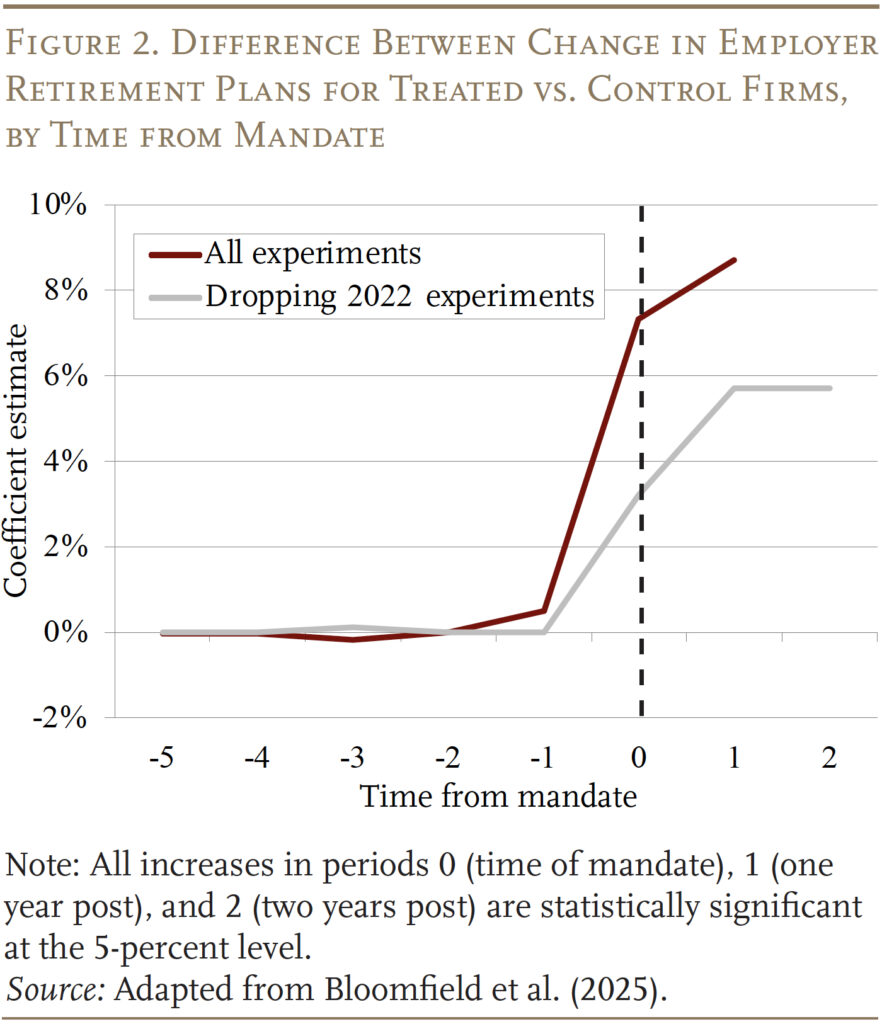

Regression analysis allows us to control for these differences. Figure 2 plots the results from the regression, which compares firms of similar sizes and at similar points in time. The figure shows two lines: 1) one that includes all seven of the mandates laid out in Table 1 (red line); and 2) one that excludes the mandates that took effect in 2022 (gray line). Excluding those mandates is useful because our data only go through 2023; thus, we can follow all treatment groups for two years post-policy instead of just one. In any case, both figures tell the same story – the share of firms offering their own retirement plans increased by 5.7 to 8.7 percentage points relative to the same-sized firms in control states during the same time period. In addition, no evidence exists of any major shift towards fewer employer plans.

The reason for this result is unclear. Firms are typically assumed to offer their own retirement plans when it is in their interest to do so. So, it is plausible that most firms that found it valuable to offer their own plan before the mandate would continue to do so instead of switching to a state auto-IRA program. However, it is less clear why firms without plans start their own plans rather than simply offering access to the state’s program, which likely imposes smaller costs on the employer. In the full study, we explore several possibilities for why some firms in this situation would adopt their own plan, including:

- employers might find the administrative burden of auto-IRAs higher than an employer plan, which they can offload to a paid third-party;

- some workers value, and thus advocate for, an employer plan relative to the auto-IRA because of higher contribution limits or the employer match; and

- employees dislike the auto-enrollment feature of auto-IRAs and advocate instead for an employer plan without this feature.

Yet, we do not find compelling evidence that any of these “rational” reasons – i.e., those related to perceived financial costs and benefits of the program – play a significant role. Instead, it seems possible that more “behavioral” factors play a role. For example, since state auto-IRA policies required firms without a retirement plan to make a choice, they may have given third-party plan vendors a good opportunity to market their products. These efforts may have convinced employers to start their own plans rather than participate in the state auto-IRAs. After all, most employers affected by the state mandates were small and perhaps unaware of existing options for employer plans until they were forced to consider them. Future research should focus on clearly identifying why auto-IRA policies have ended up boosting the adoption of employer plans, as the answer can inform future efforts to expand coverage.

Conclusion

As state auto-IRAs were being introduced, it was not clear how they would impact the number of firms offering an employer plan. One potential outcome was that firms would drop their own retirement plans in favor of enrolling their workers in the state auto-IRA. Our research suggests no evidence of this effect.

Instead, the opposite has occurred. Firms without a retirement plan subject to an auto-IRA mandate were more likely to begin offering a retirement plan relative to similar firms in other states. Thus, as more states introduce these programs, it seems likely that their effect will be twofold: 1) they will introduce auto-IRAs for workers at firms that decide not to offer their own plan; and 2) they will induce some firms without a plan to adopt their own plan.

References

Bloomfield, Adam, Lucas Goodman, Manita Rao, and Sita N. Slavov. 2025. “State Auto-IRA Policies and Firm Behavior: Lessons from Administrative Tax Data.” Journal of Public Economics: 247.

Cengiz, Doruk, Arindrajit Dube, Attila Lindner, and Ben Zipperer. 2019. “The Effect of Minimum Wages on Low-wage Jobs.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 134(3): 1405-1454.

Investment Company Institute. 2022. “The Role of IRAs in US Households’ Saving for Retirement 2021.” ICI Research Perspective 28(1). Washington, DC.

Sabelhaus, John. 2022. “The Current State of U.S. Workplace Retirement Plan Coverage.” Pension Research Council Working Paper WP2022-07. Philadelphia, PA: The Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania.

Endnotes

- See Sabelhaus (2022). ↩︎

- Bloomfield et al. (2025). ↩︎

- See Investment Company Institute (2022). ↩︎

- In most programs, savers are initially placed in a “safe” investment option in case they had intended to opt out but forgot before their money was invested. They are later moved into the target date fund. For example, in Oregon, for the first 30 days the money is held in a capital preservation fund. ↩︎

- Although firms with more than 100 workers were affected by the mandates, most of these large firms already offered retirement plans. Thus, our study focused only on mandates on firms with fewer than 100 workers. ↩︎

- Our paper excludes from the control group firms in states that implemented a version of an auto-IRA without an employer mandate, like Maryland. Firms from control states are randomly sampled at a rate of 10 percent. ↩︎

- In the full paper, we also look at plan “starts” and “stops.” ↩︎

- This statement is based on the usual assumption of parallel trends, i.e., that treated firms would have evolved in the same way as control firms but for the change in policy. Specifically, we follow the regression framework of Cengiz et al. (2019). ↩︎