Today’s Young Workers May Not Have the Housing Wealth of Today’s Retirees

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Without homeownership, it’s hard to save.

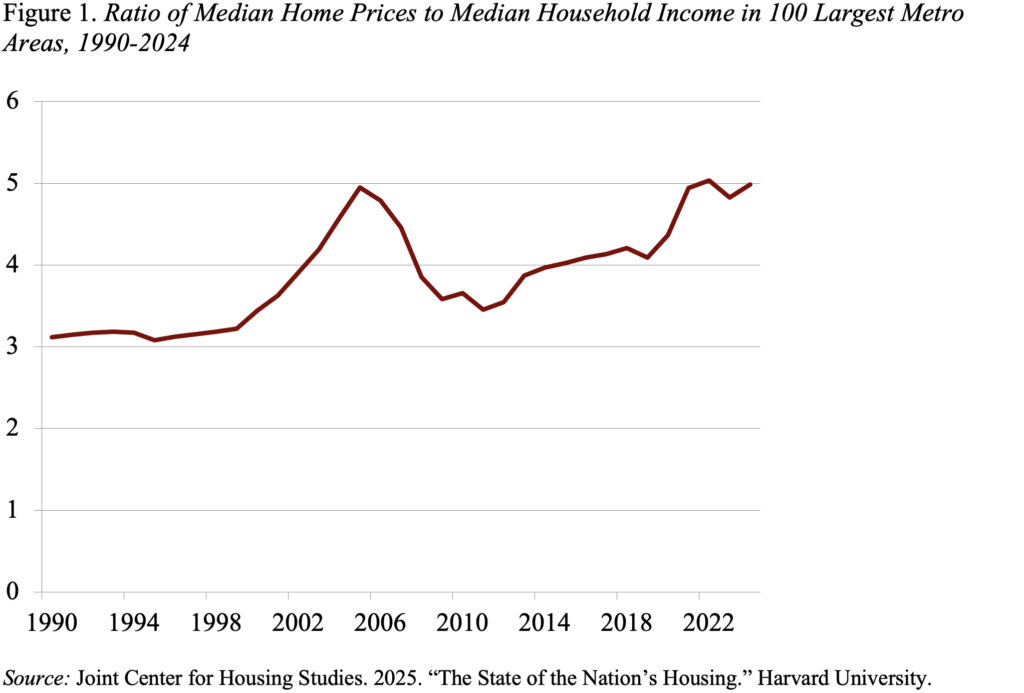

When thinking about the future of Social Security, one concern should be whether future cohorts will have comparable assets to people retiring today. Today, a major component of the typical retired household’s portfolio is their home. In fact, the house is the major asset for most families. But today higher home prices and high interest rates make it impossible for many younger households to buy a house.

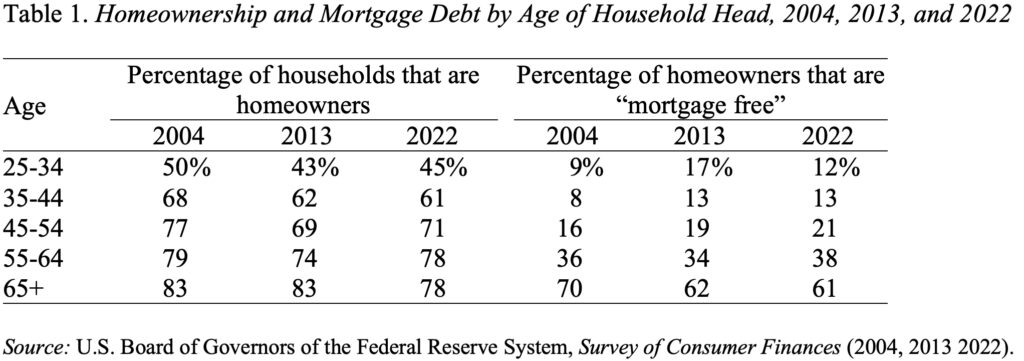

Historically, families purchased homes early in their lives, financed by a substantial down payment. Then, they built up equity in their home during their working years by paying down their mortgage and by enjoying capital gains. Even though they may have traded up to a larger house as their families grew and perhaps took on additional debt, their goal was to end up mortgage-free at retirement (see Table 1). While most households did not access their home equity to cover regular living expenses, they saw the house as insurance should they need long-term care and a way to leave a legacy to their children.

With today’s high mortgage rates and sky-high home prices, however, many young adults don’t see how they will ever own a home. The rate on a 30-year mortgage has declined slightly from 6.8 percent in the second quarter of 2025 to 6.2 percent today, but home-buying levels remain at 30-year lows. The real culprit is home prices, where the median price now stands at five times median household income (see Figure 1).

In terms of dollars, the median home cost was $412,500 in 2024, which means the potential homeowner would need $26,800 in cash to cover both the closing costs and a 3.5-percent down payment. (If the down payment were 20 percent, the required cash rises to $95,000.) Applying the standard affordability ratio of 31 percent debt to income and assuming the 3.5 percent down payment, the new owner would have to earn at least $100,000 in half of the 100 major metro areas. Moreover, the new owner would face the steep increase in insurance premiums and property taxes.

The high prices reflect a major shortage in available homes. Many owners lucky to have taken out mortgages when rates were 2 percent are reluctant to sell, and the supply has been reduced by natural disasters such as hurricanes and fires. In addition, investors in the rental market have been purchasing a large share of single-family houses, edging out – with cash and quick closing times – potential would-be homeowners. In the future, some factors may free up the supply as the “2-percenters” fade out, the baby boomers die off, or builders decide to build more housing – although one estimate suggests the new tariffs will add $12,800 to $25,000 to the building of a new single-family home.

In the meantime, many young adults – often already burdened with student debt – will end up renting. Of course, if they simply invested the savings of not owning into stocks and bonds, they could end up with a good-sized pile of assets at retirement. But that hypothesis reminds me of the advice I received from colleagues when leaving the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston at age 50 – take your benefit now – they said – you can invest it better than the boring guys who manage our pension plan. Two flaws with that approach are first my investing skills were never great, and second – more related to the renting story – I spent my pension payments eating out at nice restaurants – not saving them in an account!

One wonderful aspect of owning a home is that it serves as an automatic savings mechanism – an attribute a whole cohort of future retirees may not have. This pattern will leave them more dependent – not less – on Social Security.