Why Do Some Small Businesses Offer Retirement Plans?

The brief’s key findings are:

- Many workers lack access to an employer retirement plan, and this coverage gap is driven by small firms.

- But, in fact, about half of small firms do offer a plan, so it’s important to understand the types of these firms with and without a plan.

- Available data suggest that the small firms with a plan are larger and have workers with higher earnings and education.

- Small firms without a plan cite three obstacles: not big enough or firmly established, workers prefer cash wages, and cost.

- The first two obstacles may be insurmountable. But cost concerns might be eased by providing more information on low-cost options.

Introduction

At any given time, only about half of private sector workers in the United States are covered by an employer-sponsored retirement plan, and few workers save without one. As a result, many households end up with no retirement saving and entirely dependent on Social Security, while others move in and out of coverage throughout their careers and end up with only modest balances in a 401(k) account.1Biggs, Munnell, and Chen (2019).

Numerous studies have shown that offering a retirement plan is closely related to firm size; firms with fewer than 100 employees are much less likely to offer a plan than larger firms. As a result, observers tend to dismiss small firms as a source for future growth in coverage. In fact, though, a meaningful share of small businesses do offer retirement plans. This brief, which is based on a recent study, attempts to identify the characteristics of sponsoring firms and their employees to determine which small businesses may be more likely to offer a retirement plan in the future.2Center for Retirement Research at Boston College (2022).

The discussion proceeds as follows. The first section describes the limited information available from data sets that focus on the firms. The second section summarizes the information about firm coverage that can be gleaned from nationally representative surveys of employees. The third section explores why many small firms do not provide coverage. Surveys suggest that financial uncertainty and lack of employee interest are real hurdles. Respondents also suggest that plans are too costly, but companies are often either poorly informed or misinformed about costs. The final section offers a two-step agenda. First, the nature of plan costs should be clarified and publicized. Second, the most comprehensive survey dates from 1998, so a new survey would be invaluable.

Limited Information from Firm-based Data Sets

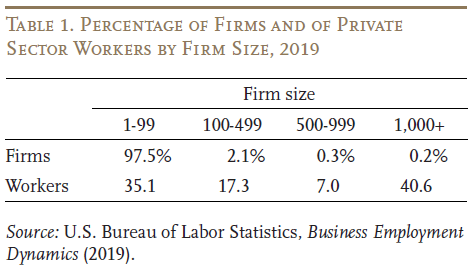

Before discussing the data challenges, it is useful to provide the lay of the land in terms of firm size and number of workers. As shown in Table 1, firms with fewer than 100 workers account for the vast majority of businesses and 35 percent of private sector workers.

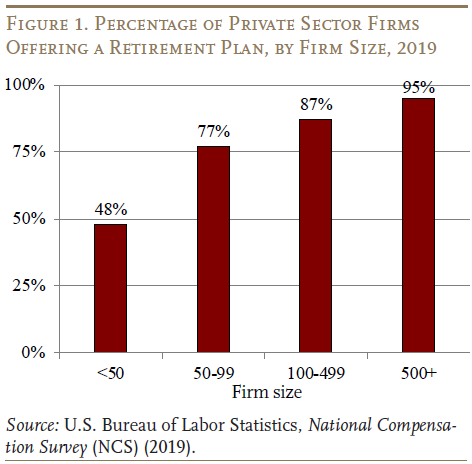

The smaller the firm, the less likely it is to offer a workplace retirement plan. Among the largest firms, 95 percent offer plans compared to only 48 percent of the smallest firms (see Figure 1).

Highlighting the characteristics of small firms that do provide coverage should be straightforward: identify the small firms with and without plans and explore the extent to which various factors are related to coverage. The problem is that no survey provides information on coverage by firm size in combination with other characteristics, such as industry, age, average wage, and provision of health insurance.

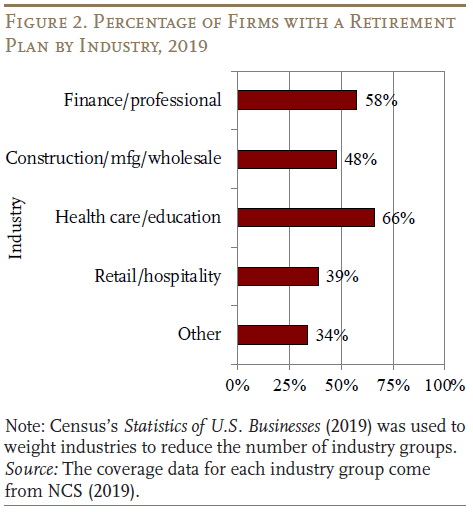

The most helpful firm-level data set is the National Compensation Survey (NCS), which, in addition to coverage by firm size, also provides coverage by industry (see Figure 2).3For simplicity, employment has been aggregated into five industry groups: finance and other professional and technical services (20% of private sector employees); construction, manufacturing, transportation, and wholesale (23%); health care and education (19%); retail and hospitality (23%); and other, which includes the official “other” category plus agriculture, entertainment, and administrative support and waste services (16%). Not surprisingly, workers in industries that typically require a college degree, such as finance/professional or health care/education have higher coverage rates. Similarly, industries with relatively higher union representation, such as manufacturing, utilities, and construction, also have higher coverage rates.4For example, in 2021, union participation in the manufacturing, utilities, and construction industries was 7.7 percent, 19.7 percent, and 12.6 percent, respectively, compared to the private sector average rate of 6.1 percent (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2022). The retail and hospitality industry, by contrast, has among the lowest coverage rates. The NCS, however, does not outline coverage by industry and by firm size, making it impossible to say anything about the importance of industry for small firms.

It turns out the only source for information about the types of small firms providing coverage is surveys of individual households.

Findings from Employee Data

Two household panel surveys – the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID) and the Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP) – provide information to identify some characteristics of small firms that offer retirement plans. The numbers reported below come from the PSID, although the SIPP produced comparable results. The first step in the analysis was to compare the PSID with the NCS to confirm the pattern of increasing coverage by firm size and the pattern of coverage by industry. The results were very similar.

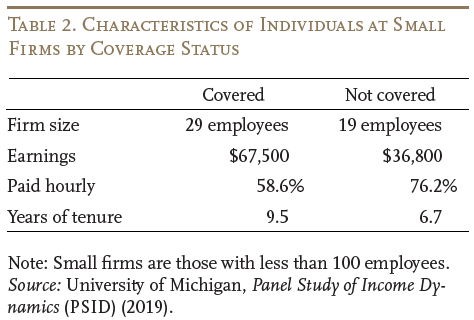

The fact that the PSID provides information on firm size, earnings, and tenure makes it possible to compare characteristics for covered and not-covered workers (see Table 2). Among small firms, average firm size does not appear to vary much by coverage provision; the firms with coverage have only slightly more employees. Earnings, however, are an important differentiator – those with coverage average $67,500 compared to $36,800 for those without coverage. Similarly, hourly workers constitute a much smaller share of covered employees than of those not covered. Finally, those with coverage have noticeably longer tenure than those without.

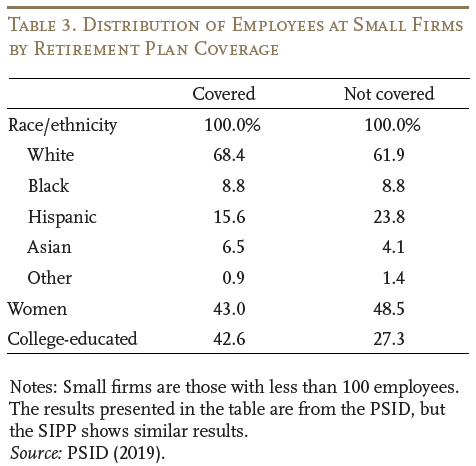

In addition to earnings, the PSID provides information on the demographic and educational attainment of employees at small firms by coverage status (see Table 3). White employees constitute a larger share of covered workers than not-covered workers, while Hispanic employees constitute a substantially smaller share. Interestingly, Black workers have relatively similar representation across coverage groups. Women account for a smaller share of covered than not-covered workers. And, as expected based on the earnings data, college-educated workers account for 43 percent of those with retirement coverage versus 27 percent of those without.

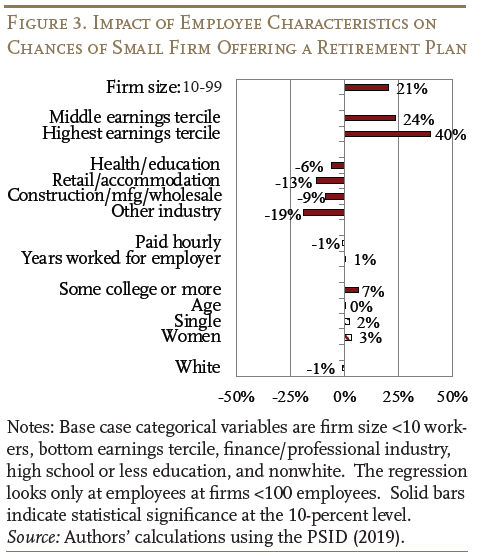

Of course, many of these characteristics associated with being offered a plan are highly correlated. Workers in the professional services and financial sector tend to be college educated and high earners. So it may be that earnings levels are driving all the results. In order to disentangle the relative importance of various factors, Figure 3 presents results from a simple linear regression relating various characteristics to the likelihood of a firm’s offering a plan. Interestingly, even though many of these factors are correlated, the earnings level of workers is not the only factor that determines whether a small firm offers retirement coverage, although it is by far the biggest factor. The size of the firm, the industry, and the educational attainment of workers also have a statistically significant effect.

Why Are Small Firms Less Likely to Offer a Plan?

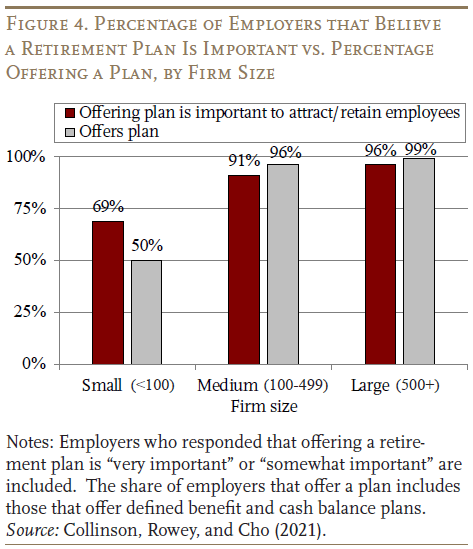

While small employers are less likely to offer a retirement plan, most still believe that offering a plan is important for hiring and employee retention (see Figure 4). However, a significant discrepancy exists for small firms between the percentage thinking retirement plans are important and the percentage offering such a plan.

The question is why, despite recognizing the value of a retirement plan, many small firms fail to offer this benefit. Identifying what firms view as impediments can also help identify those small firms most likely to offer coverage in the future. Over the last two decades, three institutions have surveyed small firms about their failure to offer a plan – the Employee Benefit Research Institute (EBRI) (1998), the Pew Charitable Trusts (2017a, b), and the Transamerica Institute (2016 and 2021). In these surveys, firms consistently cite three main barriers: the cost associated with establishing and administering a plan; uncertain revenues that make it hard for a firm to commit to a plan; and employee preferences for wages and other benefits.

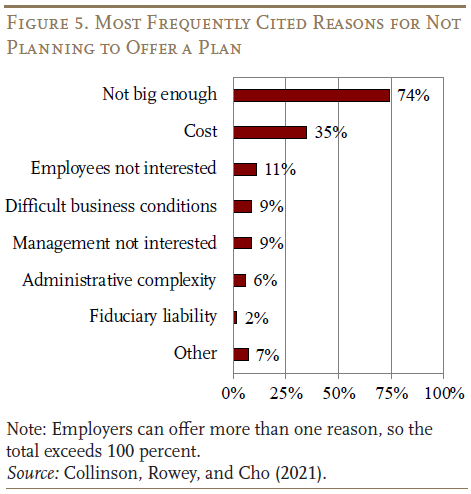

Figure 5 shows the findings from a 2021 Transamerica survey. Interestingly, the No. 1 concern in the Transamerica line-up is that the firm is not big enough, which, combined with “difficult business conditions,” suggests that the firm does not feel well enough established to introduce a workplace retirement plan. Indeed, firms that have been in business for less than five years constitute the majority of small firms. These firms may simply have too much on their plates to add an additional benefit.

Cost shows up as the second-most cited reason for not offering a plan in the Transamerica survey and always ranks in the top three. The story here, however, is a little complicated. Historically, cost and administrative complexity have always been an issue for small businesses, but Congress has tried repeatedly to minimize paperwork, recordkeeping, and reporting and fiduciary responsibility for these companies. The Revenue Act of 1978 established the Simplified Employee Pension (SEP), and 1996 legislation created the Savings Incentive Match Plan for Employees (SIMPLE). The EBRI and Pew surveys, however, both found that many employers were unaware of these low-cost options, and the EBRI survey also found that many did not realize that an employer match was not mandatory in 401(k) plans. Thus, lack of accurate information may be a significant obstacle.

The final major reason cited by employers for not offering a plan is lack of employee interest. Earlier surveys showed that small employers without a plan had a younger workforce, experienced higher turnover and paid lower wages. It is reasonable to assume that these employees would prefer cash wages over benefits; they have bills to pay and do not see any obvious money left over for retirement saving. Employers have no interest in offering benefits that their employees won’t appreciate.

Based on these surveys, several things would have to change in order for those companies not offering plans to become sponsors: Their profits would need to increase. They would need to be persuaded that their employees would value a retirement plan. And they would need to believe that a retirement plan would not be unduly costly.

Conclusion

The coverage gap is a pressing concern for the nation’s retirement income security, and the gap is driven by small employers. But, in fact, about half of firms with fewer than 100 employees do offer a retirement plan. In order to encourage growth in coverage, it is important to understand the characteristics of small firms that do and do not offer a plan.

Over decades, small firms have cited the same three major factors for not offering a plan. Two seem totally understandable and perhaps insurmountable. Some firms claim that they are simply not big enough and do not feel that they are firmly enough established to offer a plan. Indeed, many small firms are new, and it may take a few years before setting up a workplace retirement plan is a real option.

The second factor cited by small employers for not offering a plan is that their employees would prefer to get their compensation in cash wages, or, if they have to choose among benefits, they would much prefer health insurance to retirement benefits. From an employer’s perspective, it may never make sense to offer a benefit that their employees do not value. Here the evidence from the auto-IRA initiatives in Oregon, California, and Illinois may be informative. Even though lower-paid workers may not have thought they wanted a retirement plan, only about one-third of them have opted out, and testimonials suggest that many are grateful to have some money in reserve that they can either accumulate for retirement or withdraw in case of emergency.

The less compelling reason for not offering a plan is the concern that establishing and maintaining one would be too costly. Surveys have indicated a substantial lack of knowledge about the options, the costs, and even the need to provide a match in a 401(k) plan. This area seems like fertile ground to make inroads into expanding coverage – especially with the advent of PEPs (Pooled Employer Plans). If it were possible to establish a plan as part of a multiple employer plan for, say, $10,000 and maintain it for $5,000 a year (including internal costs for administration), then those numbers should be splashed in headlines in the Wall Street Journal. If those numbers are not correct, then maybe plans are too costly. In any event, clarifying the costs seems like a useful thing to do.

Finally, while recent surveys have touched on the issue of small businesses and retirement plans, the last comprehensive survey was done by EBRI in 1998. Repeating that survey – and perhaps updating it by adding information such as firm age and profitability – would be extraordinarily useful. It is simply not possible to get all the information needed about the nature of small firms, particularly age and profitability, and the characteristics of their employees from the existing data sets.

References

Biggs, Andrew G., Alicia H. Munnell, and Anqi Chen. 2019. “Why Are 401(k)/IRA Balances Substantially Below Potential?” Working Paper 2019-14. Chestnut Hill, MA: Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Center for Retirement Research at Boston College. 2022. Why Do Some Small Businesses Offer Retirement Plans? Special Report (May). Chestnut Hill, MA.

Collinson, Catherine, Patti Rowey, and Heidi Cho. Navigating the Pandemic: A Survey of U.S. Employers, 2021. Cedar Rapids, IA: Transamerica Institute.

Collinson, Catherine. The Current State of 401(k)s: The Employer’s Perspective 16th Annual Transamerica Retirement Survey, 2016. Cedar Rapids, IA: Transamerica Center for Retirement Studies.

Employee Benefit Research Institute. 1998. “Summary of Findings – 1998 Small Employer Retirement Survey.” Washington, DC.

The Pew Charitable Trusts. 2017a. “Small Business Views on Retirement Savings Plans.” Washington, DC.

The Pew Charitable Trusts. 2017b. “Employer Barriers to and Motivations for Offering Retirement Benefits: Insights from Pew’s National Survey of Small Businesses.” Washington, DC.

University of Michigan. Panel Study on Income Dynamics, 2019. Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. 2022. Union Members – 2021. News Release, Document # USDL-22-0079. Washington, DC.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Business Employment Dynamics, 2019. Washington, DC.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. National Compensation Survey, 2019. Washington, DC.

U.S. Census Bureau. Statistics of U.S. Businesses, 2019. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Commerce.

Yakoboski, Paul and Pamela Ostum. 1998. “Small Employers and the Challenge of Sponsoring a Retirement Plan: Results of the 1998 Small Employer Retirement Survey.” Issue Brief Number 202. Washington, DC: Employee Benefit Research Institute (EBRI).

Endnotes

- 1Biggs, Munnell, and Chen (2019).

- 2Center for Retirement Research at Boston College (2022).

- 3For simplicity, employment has been aggregated into five industry groups: finance and other professional and technical services (20% of private sector employees); construction, manufacturing, transportation, and wholesale (23%); health care and education (19%); retail and hospitality (23%); and other, which includes the official “other” category plus agriculture, entertainment, and administrative support and waste services (16%).

- 4For example, in 2021, union participation in the manufacturing, utilities, and construction industries was 7.7 percent, 19.7 percent, and 12.6 percent, respectively, compared to the private sector average rate of 6.1 percent (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2022).