Can You Save Your Way Out of Trouble?

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Saving more helps a little, but has big impact when combined with working longer.

The National Retirement Risk Index (NRRI) shows that half of today’s working families are “at risk” of being unable to maintain their standard of living once they retire. This result is not surprising since, at any given point, about half of private sector workers do not have an employer-sponsored retirement plan, and many who do have a plan end up saving relatively little. The question addressed in a new study is how much increased saving could reduce the percentage of households at risk.

The NRRI is based on data from the Federal Reserve’s Survey of Consumer Finances and is constructed in three steps: 1) projecting a replacement rate – retirement income as a share of pre-retirement income – for each household; 2) constructing a target replacement rate that would allow each household to maintain its pre-retirement standard of living in retirement; and 3) comparing the projected and target replacement rates to find the percentage of households at risk.

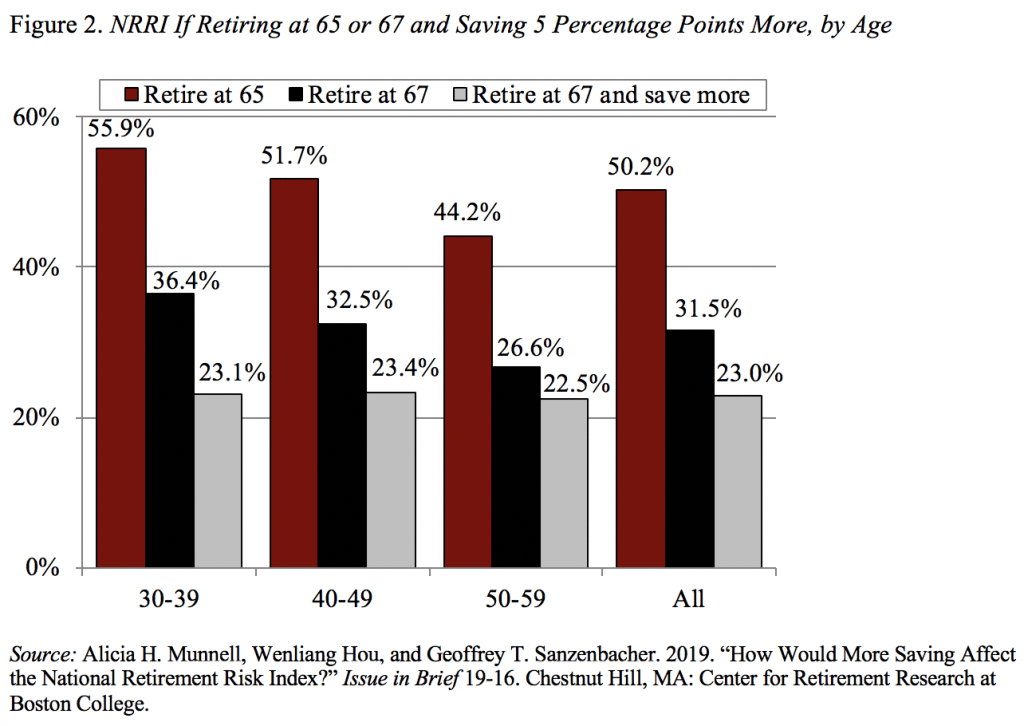

The new analysis first increased saving by various percentages for those with access to a 401(k) plan; the results show that a 5-percentage point increase in saving reduced the NRRI from 50 percent to 47 percent (see Figure 1). Assuming the availability of a retirement savings plan for those currently with no such plan at work, a 5-percentage-point increase in contributions lowers the NRRI further to 44 percent.

The impact on the NRRI of increased saving may seem surprisingly small given that 5 percentage points represents more than a 50-percent increase in the average contribution rate. To help make sense of this outcome, it is useful to consider three factors:

- Increased saving has a much larger impact on younger households (11 percentage points for households ages 30-39) than older households (3 percentage points for those 50-59), because younger workers have many years to accumulate additional assets.

- Additional saving has a much larger impact on the “savings gap” – the amount by which NRRI households fall short of their savings goal – than on the NRRI itself. Before the additional saving, the dollar shortfall for all “at risk” households combined was $7.1 trillion; increasing saving by 5 percentage points reduces the gap to $5.4 trillion. This one-quarter reduction in the aggregate dollar gap far exceeds the one-eighth drop in the NRRI.

- Third, it is hard to move the NRRI. For example, even the Great Recession resulted in only a 9-percentage-point-increase in the Index.

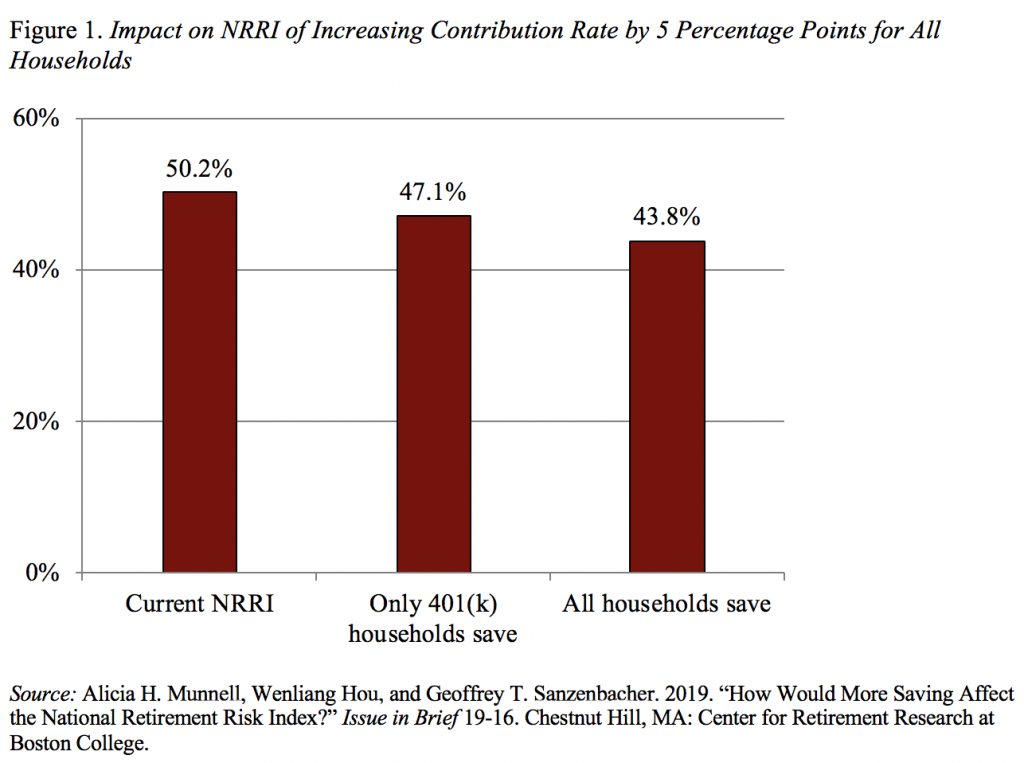

The only way to dramatically reduce the percentage of households at risk is to increase the assumed retirement age. Specifically, increasing the retirement age in the NRRI from 65 (the current assumption) to 67 (Social Security’s eventual full retirement age (FRA)) cuts the percentage of households at risk by about a third (Figure 2). The key to this impact is the structure of Social Security benefits. Monthly benefits increase by 7-8 percent per year between 62 and 70, due to the actuarial reduction before the FRA and the delayed retirement credit between the FRA and age 70. Combining the increase in the retirement age with a 5-percentage-point increase in the contribution rate results in a dramatic decline in the NRRI for all ages.