Canadian Approach to Immigration Seems Much Smarter Than Ours

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Canada to add 1.45 million immigrants by 2025 in face of aging population and low birth rates.

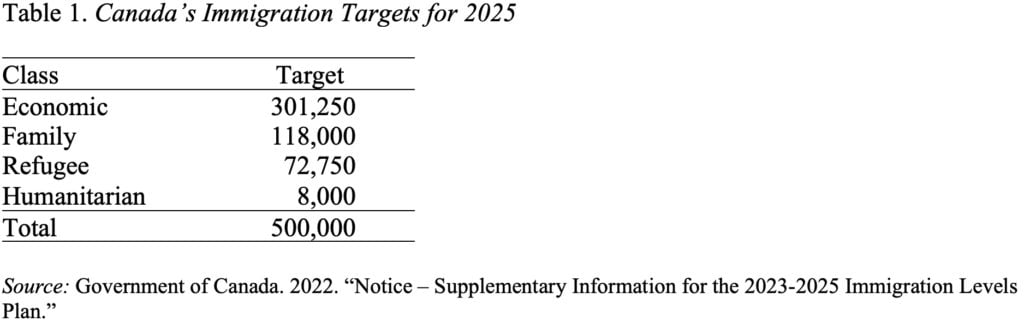

Canada just issued its immigration targets for 2023-2025, which aim to increase annual immigration from 400,000 in 2022 to 500,000 in 2025.

The desired increase is aimed at keeping Canada’s economy strong, despite having one of the world’s oldest populations and lowest birthrates. The government reports more than one million jobs unfilled throughout Canada. And immigration has become even more important in the wake of COVID, which weakened the economy and increased social spending.

Canada has four classes of target immigrants. The Economic class involves people with the requisite education, work experience, and proficiency in English or French, as well as those with Canadian work experience or graduates of Canadian institutions. The Family class includes spouses and children of Canadian citizens or permanent residents, as well as parents and grandparents. The final groups are those seeking residency for refugee or humanitarian reasons.

For those applying under the economic umbrella, the Canadian government offers an online Express Entry system. The criteria are clearly described; the applicant receives a score based on age, education, language skills, and work experience; every two weeks those with the highest scores are asked to apply for permanent residency; and applicants can expect to receive their permanent residence status in six months. The cost looks to be about 1,135 CAD for tests and background checks, and a similar additional fee for those invited to apply for permanent residency.

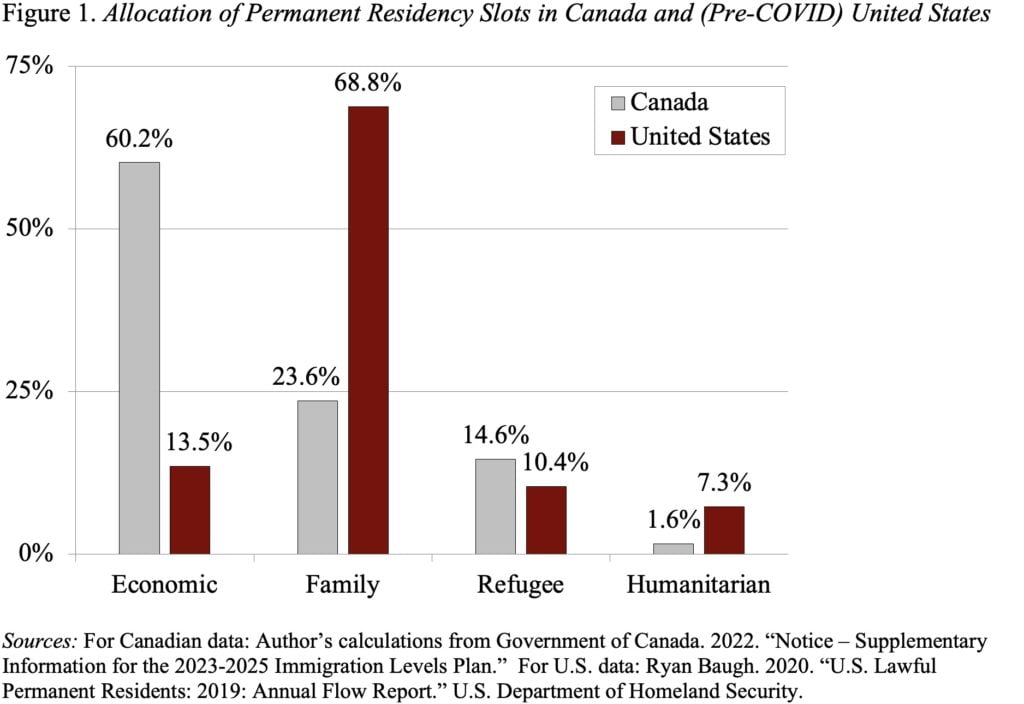

The U.S. system is characterized by “caps” rather than “targets,” involves years of waiting, and massive fees for lawyers. Most importantly, we do not acknowledge the importance of Economic immigration. In 2019, the U.S. government issued about 1 million green cards for lawful permanent residency, almost 70 percent of which went to relatives and only 14 percent to employment-based slots (see Figure 1).

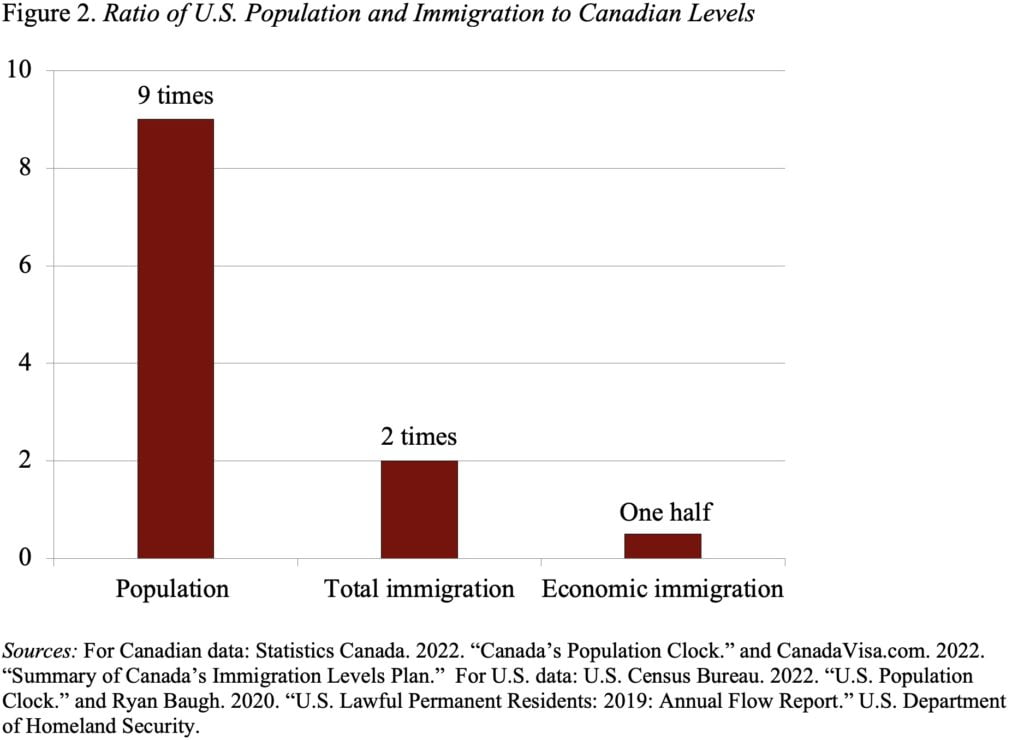

Moreover, total immigration activity in the United States is tiny compared to Canada (see Figure 2). While the U.S. population is 9 times that of Canada, our immigration numbers are only twice that of Canada’s and our employment-based immigration is less than half.

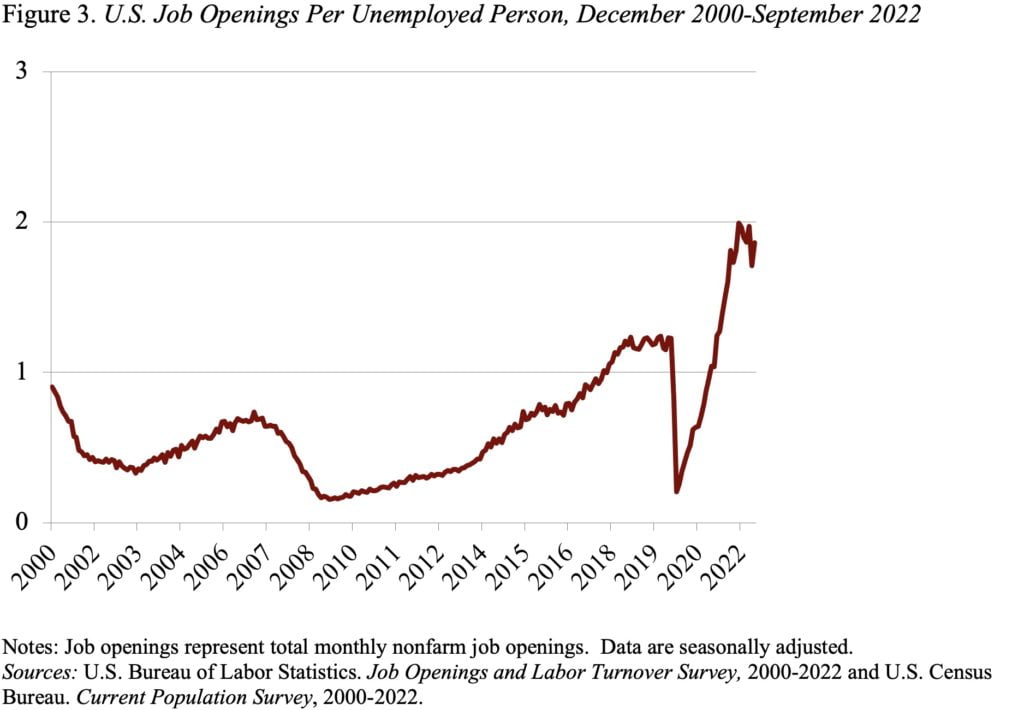

And it’s not that we do not need more workers. As shown in Figure 3, we currently have almost two unemployed workers for each job opening.

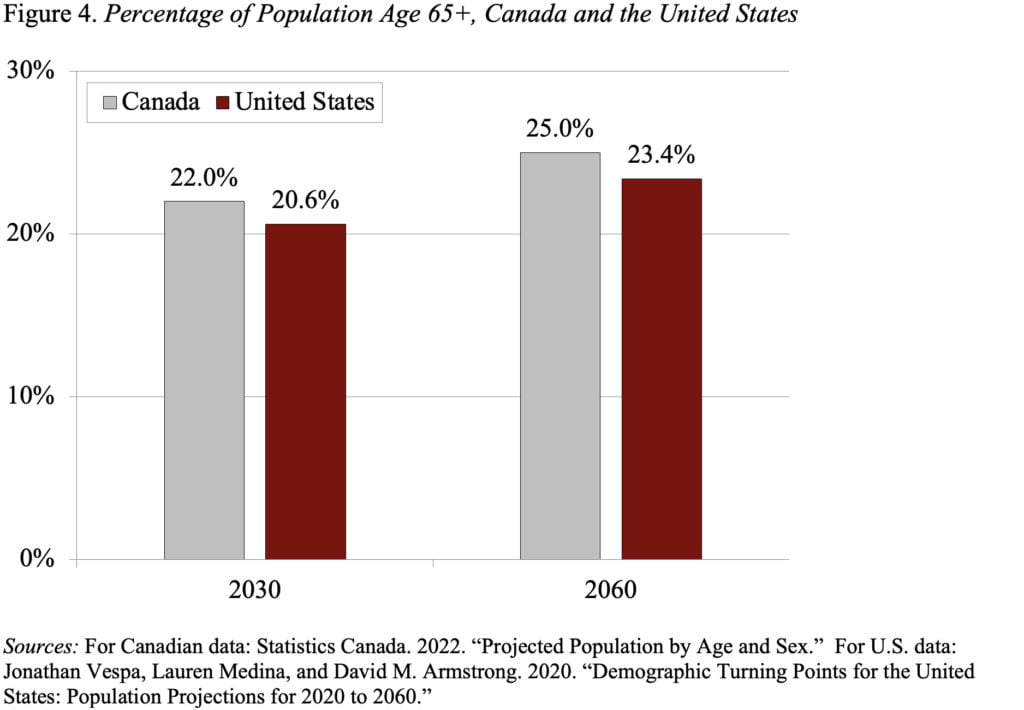

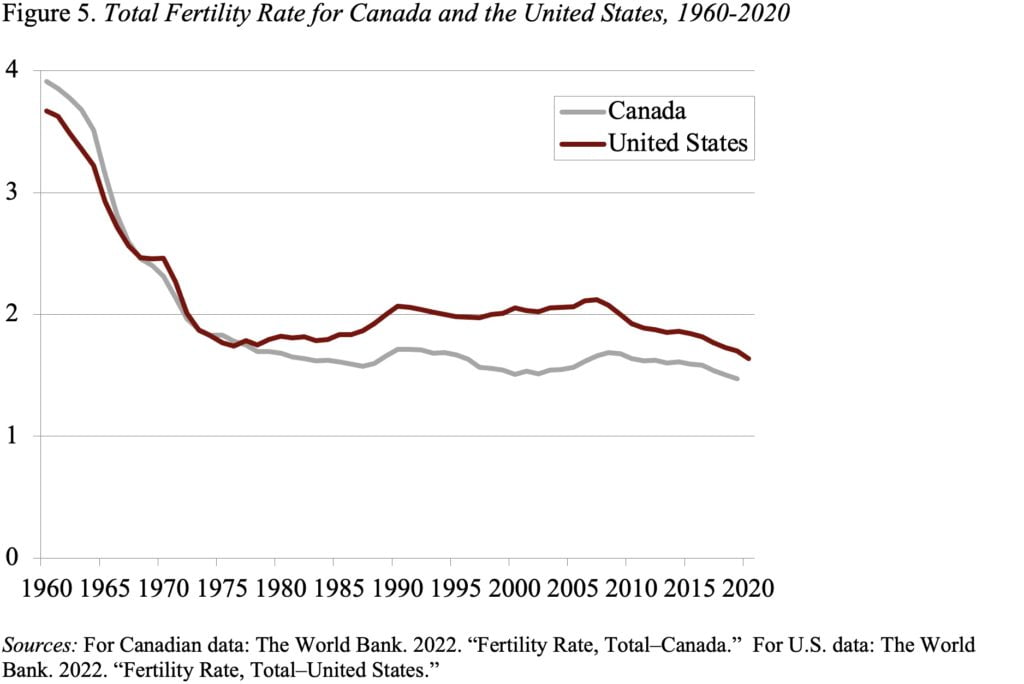

And our future does not look that much brighter than Canada’s in terms of aging and fertility. The two countries project very similar shares of the population age 65+ (see Figure 4) and the fertility rate in the United States is only slightly higher than that in Canada (see Figure 5).

In short, we should give some serious thought to updating our immigration policy.