Congress Missed a Big Opportunity in the CARES Legislation

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Maintaining the continuity of employment should be a major goal.

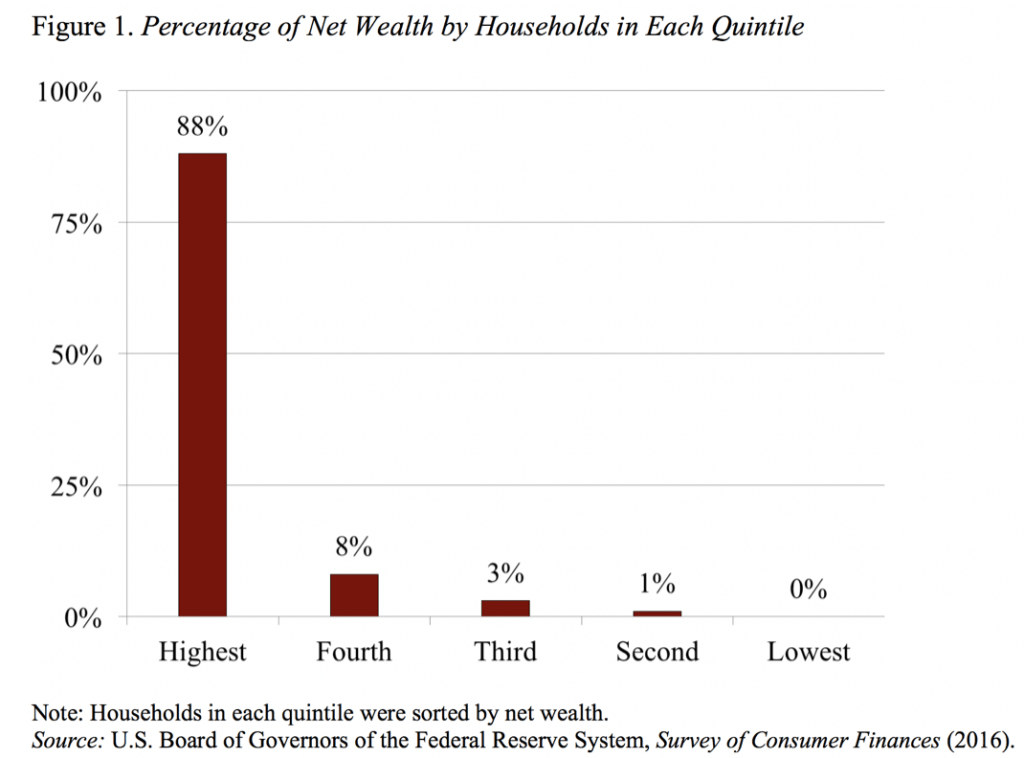

Before I say anything, let me be clear about my view of the world. At the end of 2019, according to the Federal Reserve, households held $127 trillion in assets and $16 trillion in debt, for a net worth of $111 trillion. Of course, that amount has been substantially cut by the collapse of financial markets. But the point is, of the $111 trillion, the top quintile held an estimated 88 percent and the bottom three quintiles 4 percent (based on 2016 data, see Figure 1). So any time the government wants to transfer money to workers and households in the bottom 60 percent of the population, I view that as a good thing.

And a lot of transfers are included in the third phase of Congress’ response to the COVID-19 outbreak and shutdown of the economy. Most notably, the $2 trillion Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act includes $1,200 for individuals with incomes up to $75,000, a $600 per-week increase to regular state unemployment insurance through July, and a number of other basic supports.

If transferring money were the only goal, the legislation could be given high marks. But Congress also needs to put the economy in a good position to restart once the virus is subdued. And the best way to do that is to keep people employed – not working but employed. Congress could have done what a number of other countries have done, which is to offer to compensate employers who continue to pay their workers rather than laying them off.

Denmark, an early subscriber to this approach, has received the most attention. To discourage layoffs, the Danish government has offered to pay a substantial portion of a firm’s wages and salaries until the end of June. That may be too short a period, but the program can always be extended. The advantage of the Danish approach is that it keeps workers attached to their employer, so when the epidemic is over the economy is poised to re-start.

Peter Hummelgaard, the Employment Minister of Denmark, described how the process would work for a Copenhagen restaurant employing ten people. The restaurant owner would apply to the government for help and, for hourly employees, receive up to 90 percent of the salaries – up to about $3,800 per month – which the owner would use to pay workers still employed. In addition, the government would compensate the owner for fixed costs, such as rent. In essence, the Danish approach “freezes” employment relationships by paying workers not to work until the environment clears.

In addition to economic efficiencies, I would think that such an approach would have enormous psychological benefits for the employees. They are not unemployed and forced to go through the unfamiliar application process for unemployment benefits, but rather would get their wages and salaries from their employer as usual. An additional factor, important in the U.S. but not in Denmark where they have universal health care, is that employees would be able to retain their health insurance and not be thrown onto ACA platforms or Medicaid.

Congress missed the boat in the recently enacted CARES legislation. And, in fact, it worsened the situation by making unemployment insurance so attractive, contributing to the 10 million people filing for UI over the past two weeks. But all is not lost, because we are going to need a fourth piece of legislation and, with a little time to plan and think, Congress could make maintaining employment relationships the highest priority.