Contingent Labor Force Growing Fast

Most workers quickly realize that the best solution to low earnings in a job with scant or non-existent benefits is to move on to something better.

But this is increasingly difficult to pull off, because technology and other powerful forces are reshaping the 21st century economy – and degrading the quality of the jobs that are available. As companies seek to cut labor costs, technologies like scheduling software for retail and fast-food workers and platforms like Uber and Task Rabbit are making it easier to do.

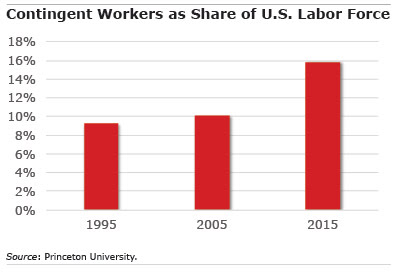

The result has been a rapidly growing contingent labor force of temp-agency workers, freelancers, independent contractors, workers for contract companies, and on-call workers with unpredictable schedules, according to a recent study by prominent Harvard and Princeton economists. They estimate that this contingent labor force has increased from 10 percent of all U.S. workers in 2005 to nearly 16 percent today. Its growth effectively accounts for all of the net job gains over the past decade.

The result has been a rapidly growing contingent labor force of temp-agency workers, freelancers, independent contractors, workers for contract companies, and on-call workers with unpredictable schedules, according to a recent study by prominent Harvard and Princeton economists. They estimate that this contingent labor force has increased from 10 percent of all U.S. workers in 2005 to nearly 16 percent today. Its growth effectively accounts for all of the net job gains over the past decade.

The transformation under way is so apparent that it has earned nicknames like the “gig,” “sharing,” or “on-demand” economy. The resulting jobs are often touted as giving workers flexibility and the freedom to earn more money – and sometimes they do. The researchers conducted their own survey of more than 3,800 contingent workers, and business consultants and computer engineers might be good examples of the independent contractors and freelancers who said in the survey that they prefer their arrangements to working for someone else.

But the reality, according to the study, has largely been negative for average workers. Most contingent workers earn lower weekly wages than similar workers in traditional employment situations. The vast majority of contingent workers in two of the lower-paid fields – temp-agency employees and on-call workers – said they would prefer steady employment.

The primary reason for the lower earnings, is “a consistent pattern [of] working considerably fewer hours per week than traditional employees,” the researchers, Harvard’s Lawrence Katz and Princeton’s Alan Krueger, wrote in their working paper.

Contingent workers are twice as likely to work part-time. They are also more likely to be women, multiple jobholders, and Hispanics, and the biggest increases have been among older workers

A report by the Aspen Institute views the rise of the contingent workforce as the latest chapter in “a long-developing trend by employers to … free themselves of obligations to employees.”

The report notes that as more low-paid workers are thrown into looser forms of employment, they often lack standard work protections and access to employer benefits like dental insurance and retirement plans. And if they can’t accrue a full-time schedule at a single establishment they might not qualify for unemployment benefits if they lose their jobs or are forced to leave due to untenable work situations.

The Aspen Institute proposed several responses. But at a time the presidential candidates in both parties are appealing to working-class men and women dissatisfied with their job prospects, we need to first acknowledge that the contingent workforce is a growing and potentially troubling trend in the U.S. labor market.

To stay current on our Squared Away blog, we invite you to join our free email list. You’ll receive just one email each week – with links to the two new posts for that week – when you sign up here.

Comments are closed.

… a growing and POTENTIALLY troubling trend? No potentially about it.

It’s simply the market telling people to move on to an occupation that is better. These things don’t happen overnight. Just paying attention to local/regional/national events will provide clear and advance notice of changes coming. Stubbornness and remaining in a job that is being “reshapen in this 21st century economy” is not the best move. Remember, it’s always about personal choices.

Your comment shows either a lack of understanding for the current situation or a complete lack of compassion. The so-called “service economy” (now the “gig” economy) always pointed to a downward income spiral for a certain group of people. In the 1980s it was skilled workers. At this time, in addition to the lack of skilled labor jobs, white collar jobs held by older workers seem to have disappeared. Many people forget that at the beginning of Depression 2.0, economists said that it could be seven years before our employment situation recovered and even then there would be many people who would be shut out. I find myself sliding from the first to the second scenario. I have a part-time job. I have sought both a full-time job and a second part-time job and neither seems to be materializing. Since the search (for me) began in 2009, I’m well into my seventh year. I am not stubbornly refusing to read the writing on the wall — and the work I do is pretty adaptable to any reshaping.

What can’t be reshaped is 30 years of experience with some of my most well-known employers falling more than 10 years down on the resume. Further, when the HR director is 35 (thank you, O Great God of Technology) you are perceived the same way we perceived our parents — old and out of touch. And when I have looked into retooling programs the predicted income post-retool is well-below what it takes to live in this city. Making things even more complicated for many of us baby boomers is the need to remain where we are geographically to assist in the care of an aging parent. That is also my story.

The true sadness of this shift in our employment situation is that it is so reminiscent of the era of the Robber Barons and the anti-union actions of the government and the wealthy. Combined, they worked to keep the “little guy” little and the “big guys” big. It’s unfortunate that we are brilliant enough to eliminate every inconvenience by throwing an app at it, but we are completely incapable of envisioning a better functioning structure for the modern workforce that allows each person the dignity of work and the hope of avoiding an impoverished future.