Could the Tide Be Turning on Reverse Mortgages?

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Just in time, the product may be entering mainstream consciousness.

After decades of skepticism and reports of scandals, the tide appears to be turning on reverse mortgages. The New York Times Business section recently led with a story on the revival of the reverse mortgage. Even more significant, for the first time a commission examining the state of retirement in the United States emphasized the importance of home equity as a retirement asset and identified the reverse mortgage as one of the major ways to tap that equity in retirement.

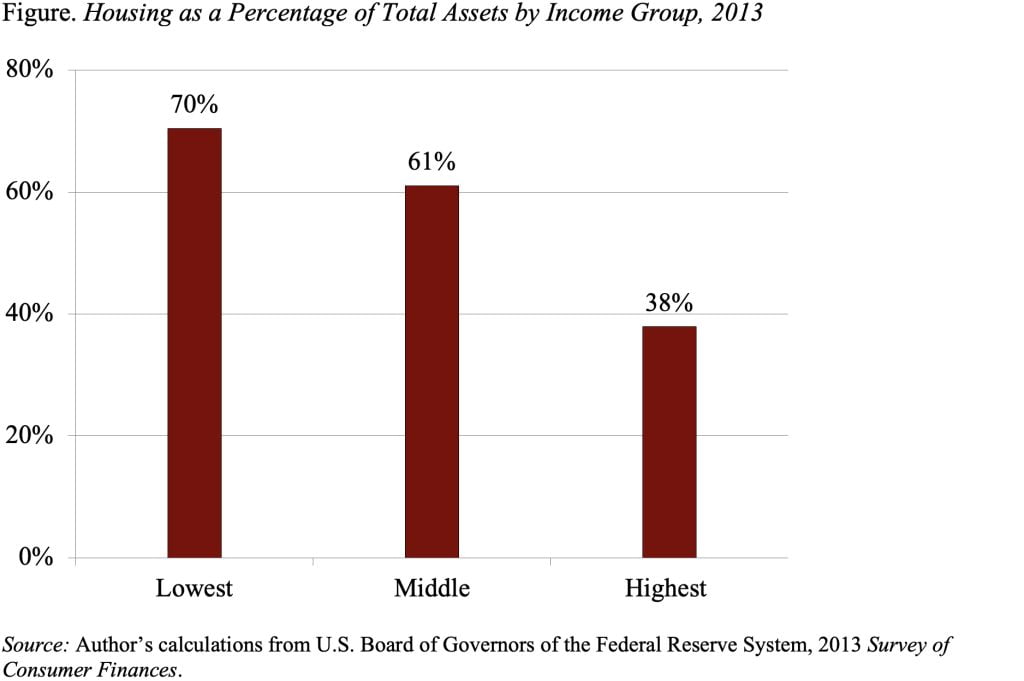

A reverse mortgage is a mortgage: a loan with the borrower’s home as collateral. But unlike a conventional mortgage, it is designed as a way for homeowners age 62 and over, with substantial home equity, to tap that equity as a source of funds to pay off their existing mortgage, cover bills or health care expenses, or to provide additional retirement income. Unlike conventional mortgages, borrowers are not required to make monthly payments. The loan must be repaid only when the borrower moves or dies. This feature is the key advantage for retirees who need more income: so long as they live in the house, a reverse mortgage does not add a claim on the income they already have. Accessing home equity will become increasingly important in a world where retirement needs are expanding – people are living longer and face rapidly rising health care costs – and the retirement system is contracting – Social Security replacement rates (benefits as a percentage of pre-retirement earnings) are declining and employer-provided pensions have shifted from defined benefit plans to 401(k)s, which require individuals to bear all of the risks. Reverse mortgages offer a mechanism for tapping home equity for those who want to stay in their home. And for most low- and middle-income households, home equity is their major asset (see Figure).

Ron Lieber in the New York Times article noted that reverse mortgages have moved from a product sold on late-night TV by Pat Boone and Henry Winkler to one offered by community bankers across Pennsylvania (and probably many other states). Dollar Bank, which was established in 1855 and makes loans in the Pittsburgh area, has a loan officer dedicated to reverse mortgages and makes about 100 reverse mortgage loans a year. Fulton Bank in Lancaster also signs up 100 customers a year. Both banks try to get customers to come in with their families so everyone knows what it means to tap the equity in the home. The customers who end up taking out the loan appear to be pleased with the product. And the fact that community bankers are offering reverse mortgages is lending respectability to this “much–maligned” but increasingly necessary product.

The necessity of tapping home equity was also recognized by the Commission on Retirement Security and Personal Savings, a panel of experts convened by the Bipartisan Policy Center and chaired by Kent Conrad, a former Democratic U.S. Senator from North Dakota, and Jim Lockhart III, a Republican who had served as Director of the Federal Housing Finance Agency, Principal Deputy Director of Social Security, and Executive Director of the Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation. The Commission acknowledged that people are not going to have enough money to retire comfortably and that the $12.5 trillion in home equity rivals the $14 trillion in retirement assets. The Commission stated that reverse mortgages can be a good option for some older Americans, proposed ways to strengthen programs that advise consumers on reverse mortgages, and also suggested establishing a small-dollar reverse mortgage that could reduce fees for consumers and risks for taxpayers.

It does seem, at long last, that reverse mortgages are entering mainstream consciousness. And it may be happening just in time to help millions of Americans who will retire with grossly inadequate 401(k) balances to have a decent standard of living when they stop working.