Dallas Police and Fire Pension Saga Is a Cautionary Tale for Others

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

To avoid Dallas’ plight, pension boards should monitor their plans for aberrant behavior.

I started to follow the situation in Dallas because the press had begun characterizing the crisis facing the Dallas Police & Fire Pension System as the tip of the iceberg of state and local plans. My view is that it is a story of wild investments that produced large losses, along with a very large and excessively generous Deferred Retirement Option Program (DROP). (A DROP is an arrangement under which employees entitled to retire continue working and have their monthly benefit deposited in a notional account where it accrues interest and can be taken out as a lump sum.)

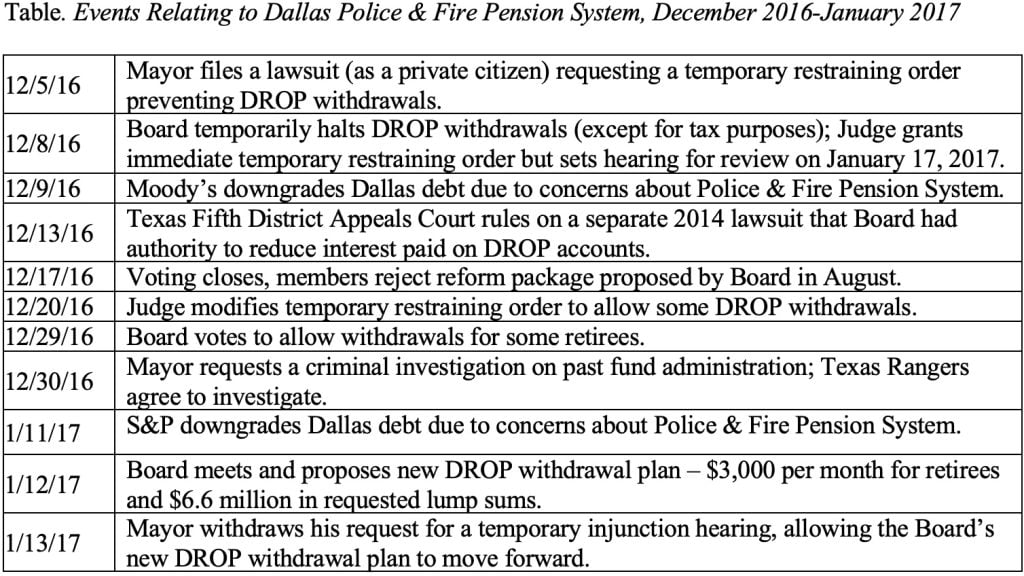

For those of you who do not follow the situation in Dallas, poor investment policy and consistent underfunding in the Police & Fire Pension System resulted in a decline in the funded ratio from 72% in January 2011 to 45% in January 2016. Subsequently, in 2016, when the DROP participants caught wind of talks to reduce their benefits, they took notice of the steep decline in asset values and started withdrawing their money, exacerbating the problem. The funded ratio in December was probably around 35%. Subsequent developments in this saga have been fast and furious. The main players are the Mayor of Dallas, the Police & Fire Pension Board, Judge Tonya Parker of the 116th District Court, and the bond rating agencies (see Table).

Dallas, a fast-growing vibrant city, has a lot at stake here, with the Police & Fire Pension System slated to run out of money in 2027. In its August reform proposals, the Police & Fire Pension Board requested that – in exchange for benefit cuts – the city contribute $1.1 billion to reduce the underfunding. But that amounts to almost all of the city’s general revenue funds and would only increase the funded ratio from 35% to 53% and extend the exhaustion date by only a few years. Moreover, members have since rejected the reform package. So Dallas is back to square one.

At present, the Board is working with the City to construct a new set of reforms to submit to the Texas legislature for review in the 2017 session.

The real problem here is that nobody was watching as the Board undertook a decade of bizarre investments and paid an 8.5 -9.0 % return on the DROP accounts. The Board could have disciplined itself if it had looked at comparative data each year on its asset allocation and the nature of its DROP. The fact that Dallas had 68.4% of its assets in alternative and real estate investments compared to 21.8% for state and local plans generally should have raised a red flag. The fact that it had a very generous DROP plan should also have been alarming.

Pension boards should be required to do the very simply exercise of comparing themselves with plans nationwide, along five or ten dimensions. The data are readily available and would flag aberrant behavior such as that in Dallas.