Don’t Bring Back Traditional Private Sector Defined Benefit Plans

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

They’re not good for workers and distract from the key issue: continuous coverage.

Something I don’t understand about some of my colleagues is their enthusiasm for defined benefit plans – more specifically for “traditional” plans where benefits are equal to, say, 1.5 percent of final salary for each year of service, where final salary is defined as the last five years, and benefits are not adjusted for inflation after retirement.

Traditional defined benefit plans would not be good for many private sector workers – a point driven home by our recent bout of inflation. Inflation erodes the value of benefits in the accumulation phase and erodes the real value of unindexed benefits in retirement.

The lack of indexing of defined benefit pensions is obvious; millions of households have seen the purchasing power of their benefits decline by more than 20 percent since inflation took off in 2021. That’s a permanent loss that can never be recovered.

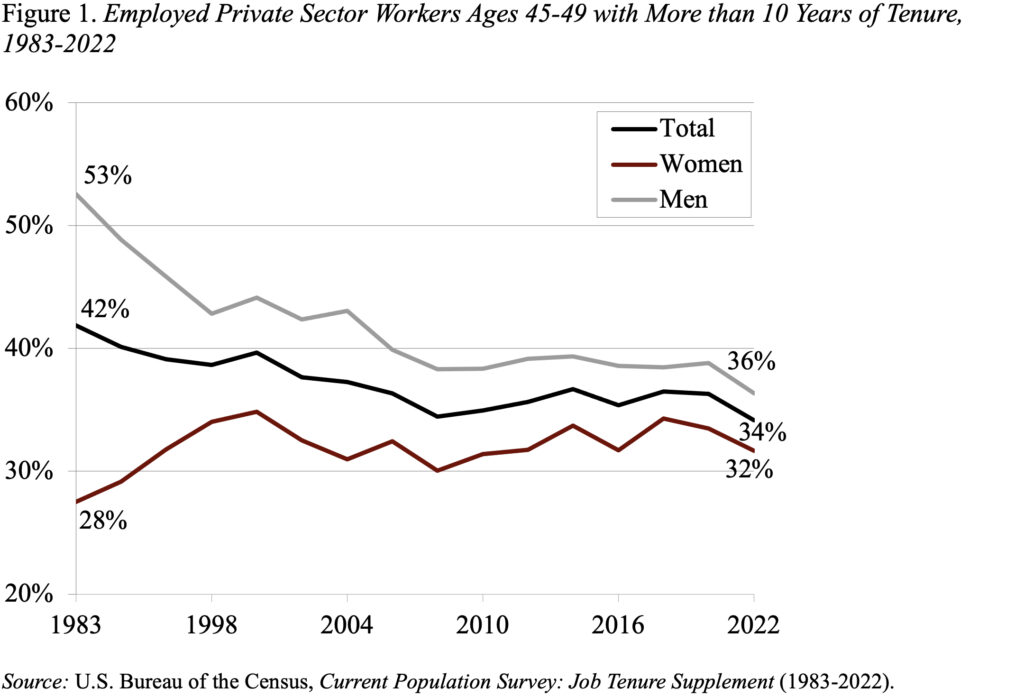

What is less obvious is the effect of inflation on the accumulation side of defined benefit pensions, where shifting jobs seriously erodes retirement income. And workers do shift jobs. Among those ages 45-49, only about a third of workers had been with their employer for more than 10 years (see Figure 1). While the question of whether mobility has increased over time is controversial, the fact that the U.S. has a very mobile workforce is uncontroversial.

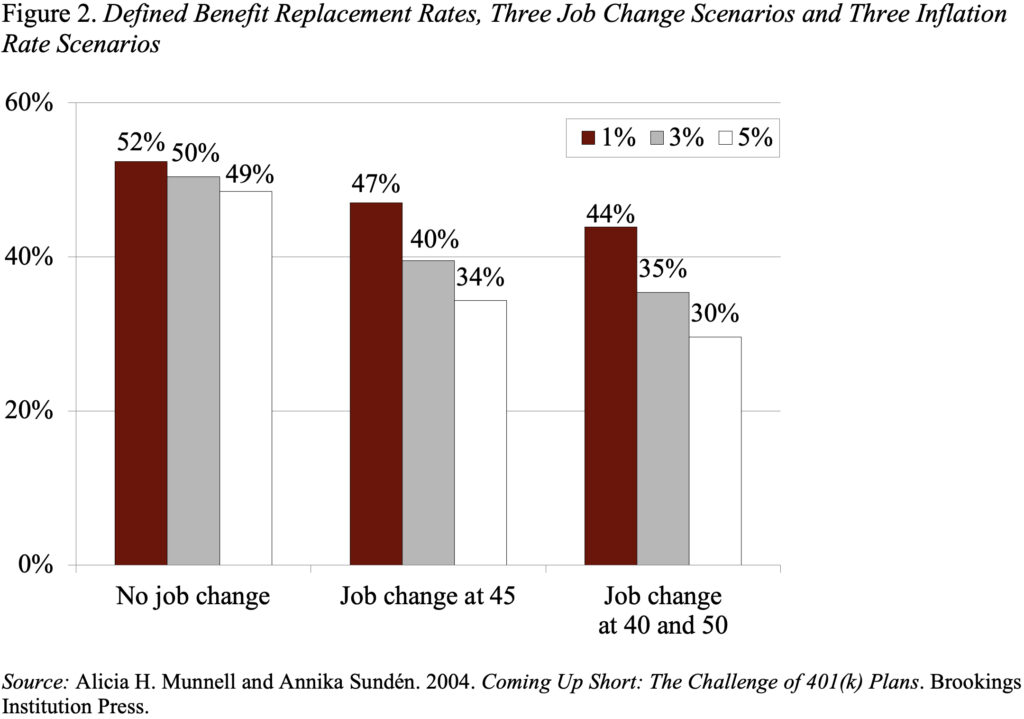

Combining job shifting with inflation means that workers with defined benefit plans experience a significant reduction in their retirement income. That is, workers with such plans who change jobs, even among firms with identical plans and immediate vesting, receive significantly lower benefits than workers with continuous coverage under a single plan – assuming these workers have the same future earnings path as they would have had without the job change. The reason job changers have less retirement wealth is because their benefits are based on earnings at the time they terminate employment. Workers who do not change jobs see the earnings used for the calculation of retirement benefits rise over their careers, due to inflation and productivity growth. Job changers, however, lose the increase in their retirement benefits generated by this growth in nominal earnings. These differences are greater if inflation is faster, because final earnings from earlier jobs become increasingly insignificant with rapidly rising wages (see Figure 2).

The only way for mobile employees to avoid such losses under traditional plans would be for the employer to provide benefits based on projected earnings at retirement rather than at the time that the worker leaves the job. Improving benefits for terminated employees, however, would either cost the employer or lower benefits for remaining employees. Traditional defined benefit plans are not a good bet for mobile workers in an inflationary environment.

An even bigger concern, however, with the nostalgia about traditional defined benefit plans is that it is a diversion from the most important issue for retirement security – namely, ensuring workers have continuous coverage over their work lives. At any time, about 50 percent of private sector workers do not participate in a workplace retirement plan. That issue is much more important than whether those with continuous coverage have a defined benefit or 401(k) arrangement.