High Tax Rates for the Wealthy

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

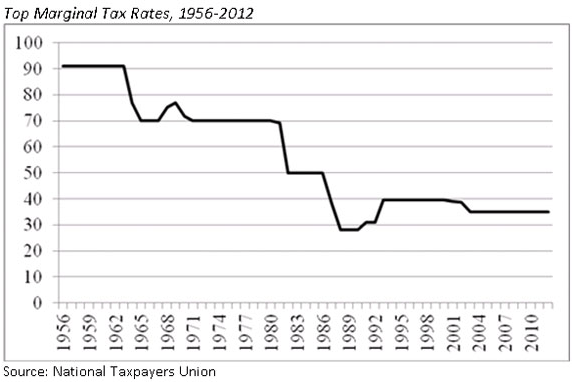

The Congressional Budget Office projects that, with the current trajectory of taxes and spending, debt will rise from its current level of about 70% today to nearly 95% in ten years and twice that high by 2040. It is inconceivable that we can avoid such an outcome without raising taxes. But the current tax debate focuses on Bush versus Clinton – that is, maximum rates of 35% versus 39.6% – whereas new work by economists suggests that the more relevant debate should be Reagan versus Nixon – maximum rates of 50% versus 70%.

The top 1% is a good place to look for additional revenue. The share of pre-tax income accruing to the top earners has increased from less than 10% in the 1970s to about 20% today. And, as noted above, the tax rate has declined sharply.

Raising rates on top earners has traditionally been thought to produce little revenue. Indeed, the famous backward-bending Laffer curve, which Arthur Laffer drew on a napkin to make a point to Gerald Ford’s chief of staff Donald Rumsfeld and assistant Dick Cheney in 1974, showed that revenues would increase less and less as rates rose and, after some point, revenues would actually decline. The notion is that if rates got too high, rich people would find ways to avoid them; they would work less, shift their earnings to other forms, move money overseas, and otherwise reduce their income. The message was that high taxes would reduce efforts by the rich and reduced efforts by the rich would slow economic growth.

Until recently, the Laffer curve was accepted as gospel. But new research by economist Peter Diamond, the 2010 winner of the Nobel Prize, and Emmanuel Saez, a John Bates Clark medalist for the best economist under 40, and others, suggests that the top rates for high earners could be much higher without hurting growth. The Diamond-Saez research indicates that the revenue maximizing federal tax rate is between 50 and 70 percent, even acknowledging that the rich face additional Medicare taxes and state and local levies. To reduce tax avoidance, tax rates on capital gains and dividends should match that on earnings. Such a levy would produce about $4 trillion over the next 10 years – a nice down payment on solving the long-term deficit problem.

But how about economic growth? The truth is that there is actually very little evidence to support the argument that high taxes on the rich slow growth. In the United States, per capita growth was much slower between 1980 and 2010 when top marginal tax rates were low than between 1950 and 1980 when rates were high. Internationally, growth and tax rates are not related among OECD countries.

The reason that very high marginal rates would not affect growth, according to Saez and co-authors, is that much of the income generating activity of the top 1 percent does not contribute to growth. On the other hand, the potential $4 trillion of tax revenues could be put to productive use. If it were simply used to reduce federal debt, it would increase investment and stimulate growth. If it were used to enhance education or repair dilapidated infrastructure, it would have an even larger pro-growth effect.

While the new research is certainly generating controversy, it does suggest that the tax debate should be broadened. Dramatically higher tax rates on the top 1 percent would produce enormous revenues, improve the distribution of income, and most likely lead to greater economic growth.