How Has the Shift to Defined Contribution Plans Affected Saving?

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

National Income and Product Accounts data show no decline.

Many commentators – ourselves included – assert that people are saving less for retirement as a result of the shift from defined benefit to defined contribution plans. To support such an assertion, it would be nice to have counterfactual data showing what the world would look like today in terms of retirement saving if workers were still covered by defined benefit plans and compare that saving with actual contributions to defined contribution plans. But these data do not exist. Furthermore, even if these data did exist, today’s more mobile workforce would make defined benefit plans a less effective way to save for retirement than they were in the past. So such an exercise simply is not feasible.

Interestingly, it is possible to get some idea about what is going on by looking at data in the National Income and Product Accounts (NIPAs). These data used to show contributions to both defined benefit and defined contribution plans. Contributions to defined benefit plans, however, provided little information about pension saving because, when the stock market booms, employers’ contributions can drop to zero as they rely on investment returns to fund accruing benefits. In 2013, the government changed accounting for defined benefit plans from a cash basis to an accrual basis. That is, instead of reporting how much an employer contributes to a defined benefit plan, the NIPAs now report how much participants in a plan are accruing in benefits. A forthcoming study from the Center uses these new data to provide some insight on how pension saving has changed over time.

We make a number of adjustments to the raw data. On the defined benefit side, we standardize for declining interest rates over time and move to a broader definition of pension liability. On the defined contribution side, we eliminate rollovers from the contribution data and take account of leakages. Because other researchers may prefer to make different adjustments, the data will be available for interested parties to play with.

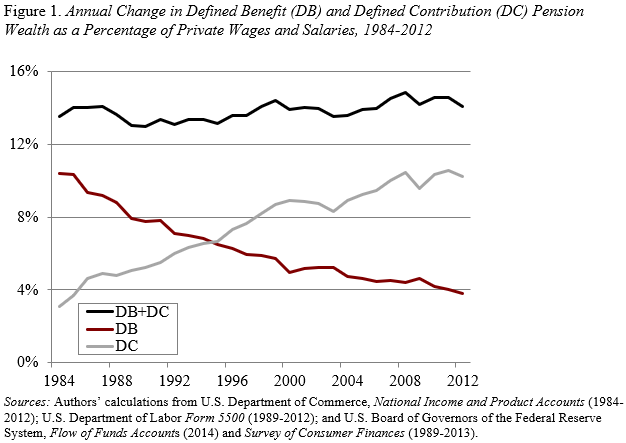

The adjusted data show that, on balance, the decline in defined benefit plan accruals has not been fully offset by rising contributions to defined contribution plans, leading to a slight overall decline in retirement saving.

Contributions, however, do not tell the whole story. Pension wealth also goes up by the return on accumulations. When returns on accumulations are added to contributions, the annual change in pension wealth appears to have remained relatively steady over time (see Figure). This pattern reflects that individuals covered by 401(k) plans have taken more risks than participants in defined benefit plans, and the high returns associated with risky investments have produced substantial asset accumulations.

We are going to have to change our story! Overall, people are not saving less for retirement as a result of the shift from defined benefit to defined contribution plans. Of course, the nature of the accumulation process and the distribution of risks have shifted dramatically. The effect of these shifts, however, can be identified only by looking at data on individuals as opposed to those from our national accounts.