How to Explain an Uptick in the Percentage of the Population Retired?

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Fewer people are ‘unretiring,’ but that will likely change.

This stuff about older workers is driving me crazy. I thought we had a story, and then folks put a new ball on the table.

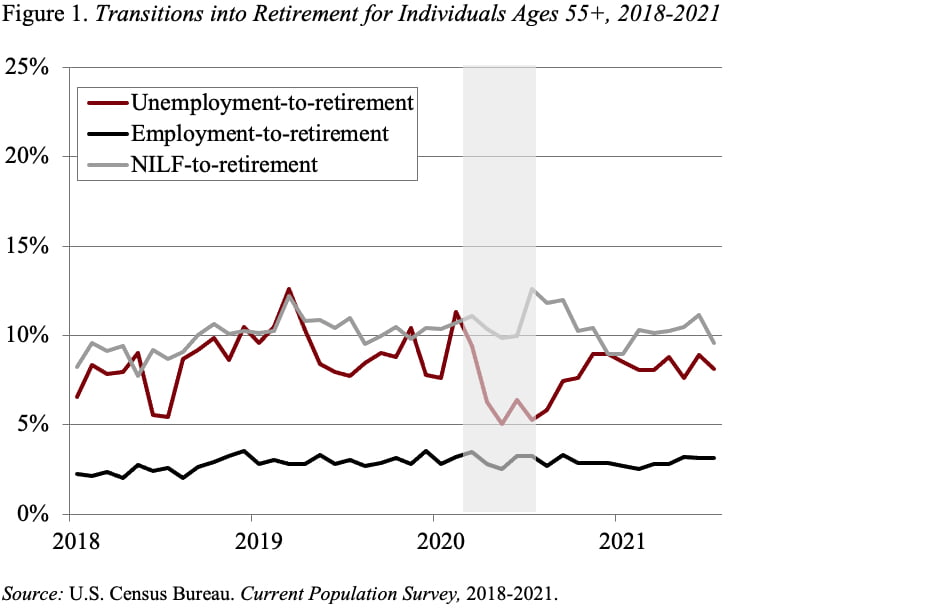

Our basic story has been that older workers, like all workers, were hurt by the pandemic and ensuing recession. Their experience was a little worse than that of prime-age workers, but not as bad as that of younger workers. Some older workers returned to the labor force as the economy improved, but a large number remained “not in the labor force.” Interestingly, we have not seen any uptick in self-reported retirement (see Figure 1). Month-to-month transitions from employment to retirement and from not-in-the-labor-force (NILF) to retirement have both been flat, and transitions from unemployment to retirement have, if anything, declined from pre-pandemic levels.

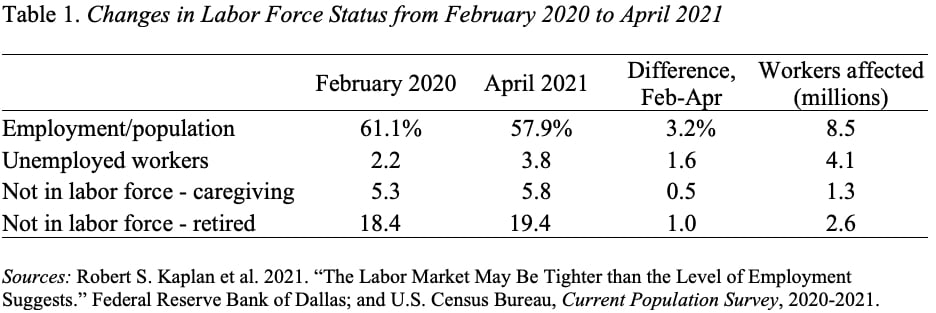

Ok. Then along comes the Dallas Fed exploration of the decline in the ratio of employment to population, showing that 1.0 percentage points of the 3.2-percentage-point decline can be explained by higher retirements (see Table 1). They calculated that 0.4 percentage points can be attributed to the aging of the population and the additional retirements account for 0.6 percentage points or 1.5 million workers.

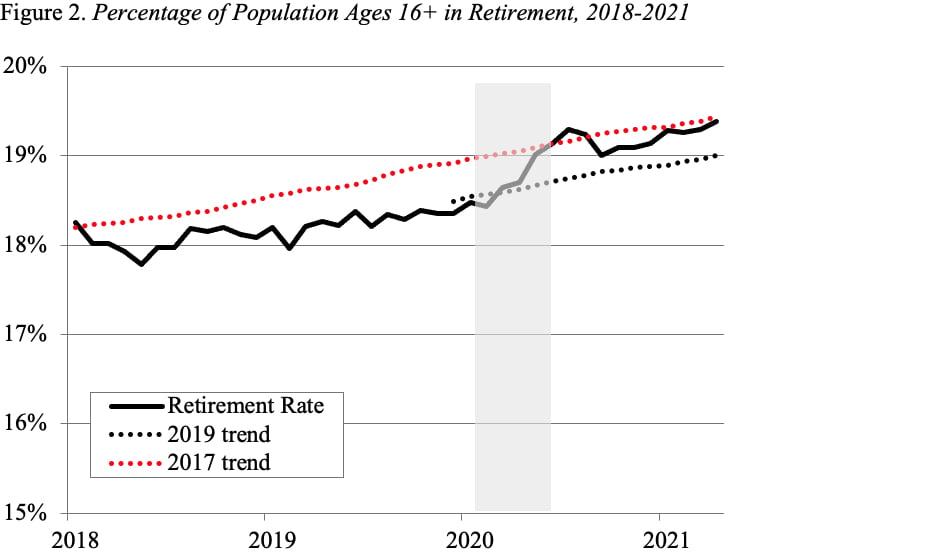

So suddenly, we have an uptick of 1.5 million retirees, as shown in Figure 2. It’s really a funny phenomenon, however, since the hot labor market of 2018 and 2019 caused many older workers to delay retirement, resulting in a ratio of retirees to population below what 2017 retirement rates would have predicted for the aging population. Nevertheless, it’s still really annoying since we had not seen an increase in people moving into retirement.

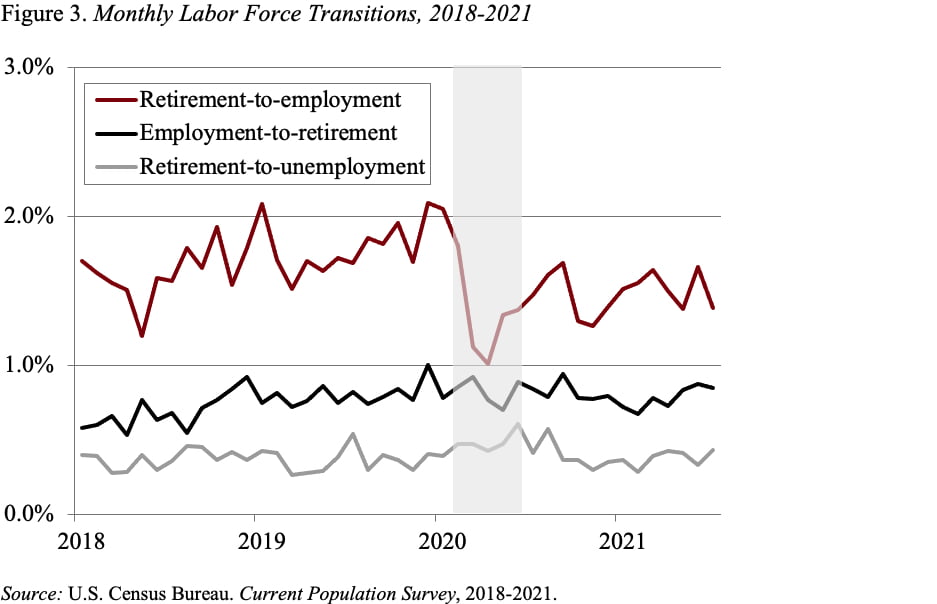

If people are not moving into retirement, how can the ratio of retirees to population tick up? Fortunately, a piece by the Kansas City Fed provides an answer. As described above, the transition from work to retirement remained steady over the entire period (see Figure 3). Similarly, the line covering retired workers who have started to look for work but are not yet employed also held steady. The really interesting pattern is that the red line – those moving from retirement to work – dropped sharply with the onset of the pandemic and has remained low. That is, the COVID uptick was driven not by an increase in the number of employed people transitioning into retirement, but by a decline in the number “unretiring” – that is rejoining the labor force.

Will the “unretiring rate” pick up? Two factors suggest it will. First, the retirement-to-employment rate did not plummet during the Great Recession, which suggests the drop in early 2020 reflected health concerns related to the pandemic. As the health risk recedes, more people may come out of retirement to work. Second, the increase in the share retired included 1.2 million people under age 68, who are likely quite capable of work.

I wish that I had figured this out, but as an old Fed person I’m delighted our central bank is on the case!