How to Reverse Reverse Mortgage Exits?

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Bad news for retirees. The two biggest players in reverse mortgages exited the business. Bank of America (#2) quit in February and Wells Fargo (#1) in June.

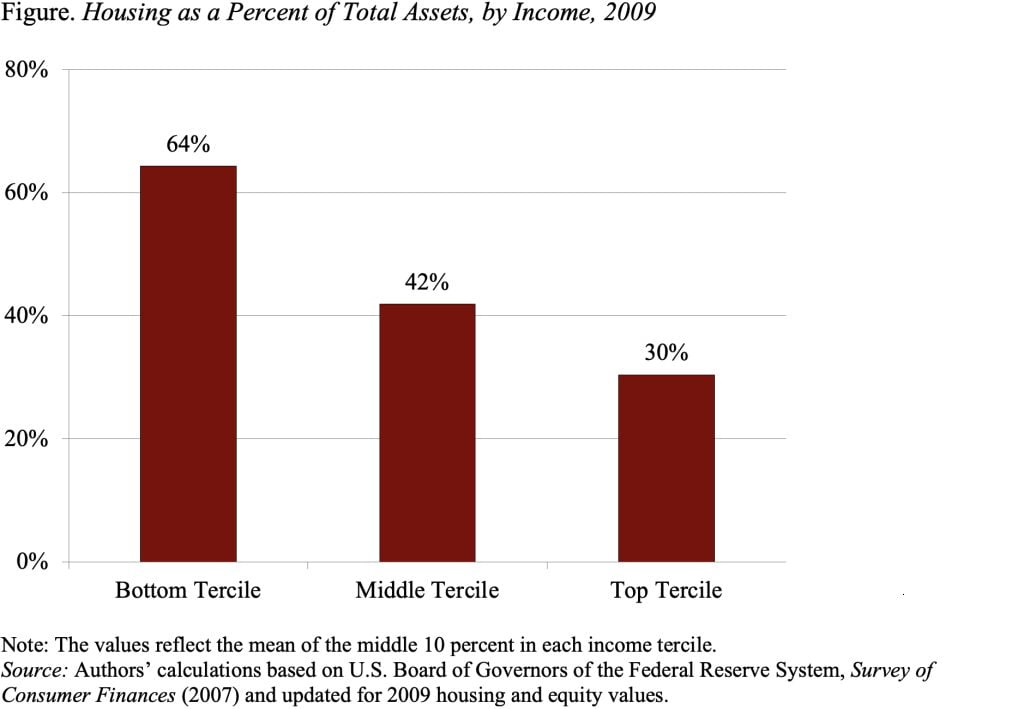

Reverse mortgages enable people 62 and over to tap their home equity. And despite the bursting of the housing bubble, the house is a crucial component of most households’ assets (see Figure). Accessing this equity will become increasingly important in a world where retirement needs are increasing – people are living longer and face rapidly rising health care costs – and the retirement system is contracting – Social Security replacement rates are declining under current law and employer-provided pensions have shifted from defined benefit plans to 401(k)s with modest balances.

Reverse mortgages allow households to remain in their home, take out a loan, and pay off the loan plus accumulated interest when they die, move out, or sell the house. The loan can be taken as a lump sum, line of credit, lifetime income, or as a payment for a specified period. To date, the line of credit has been the most popular option. The borrower remains responsible for paying property tax and homeowner’s insurance.

The most widely used reverse mortgage is the Home Equity Conversion Mortgage (HECM), which is insured by the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). HUD offered the HECM Standard in 1989 and in 2010 issued the HECM Saver, which sharply cut the fees and somewhat reduced the size of the potential loan. Loans are available on values up to the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) limit of $625,500.

The amount available to a homeowner through a reverse mortgage depends on three factors:

- Home value: the more valuable the home, the larger the loan.

- Interest rate: the higher the interest rate, the more rapidly the outstanding balance will increase, so the smaller the loan as a proportion of the value of the house.

- Age of borrower: the older the borrower, the less time for interest to accrue, so the larger the loan.

Reverse mortgages have been criticized as being too expensive with high upfront fees; the HECM Saver attempts to address this concern. Reverse mortgages have also received bad publicity regarding aggressive salesmen persuading elderly borrowers to invest their proceeds in inappropriate products. Despite these issues, reverse mortgages are a product that more and more households will need.

Unfortunately, reverse mortgages are not a profitable line of business in a world of recession and declining home prices. The recession makes it difficult for many borrowers to keep up with required property tax and mortgage insurance payments, which can lead to technical defaults. No bank wants to be forced to foreclose on a vulnerable elderly homeowner. Declining home prices mean that lenders soon see a crossover point where the loan is bigger than the value of the house, and it also means that fewer homeowners qualify for loans.

We need some creative thinking to design a better mousetrap that will enable retirees to tap the equity in their home. They are going to need the money.