Let’s Take Advantage of the Fiscal Cliff

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

If you believe, as I do, that higher taxes should be part of solving the nation’s debt and deficit problems, then the fiscal cliff should be viewed as an opportunity as well as a threat. Including taxes as part of the solution is hardly an extreme position; both the Bowles-Simpson and the Domenici-Rivlin plans include taxes in their packages. But many Republicans have signed Grover Norquist’s pledge never to raise taxes, so increasing tax revenues by letting tax cuts expire is a wonderful opportunity.

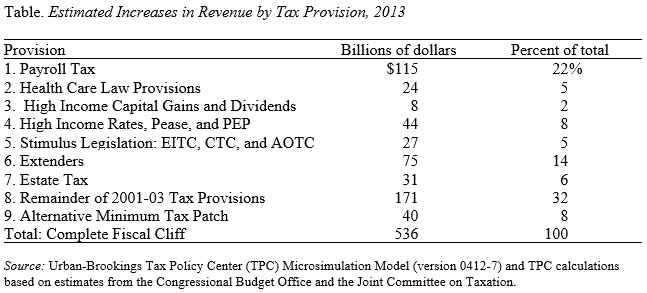

According to a recent study by the Urban Institute-Brookings Institution Tax Policy Center, taxes would rise about 20 percent in 2013 if no action were taken. These increases result from six factors: 1) the Bush tax cuts, which were enacted in 2001-03 and extended for two years in 2010, are set to expire; 2) temporary tax cuts for low-income individuals, enacted as part of the stimulus in 2009 and also extended for two years in 2010, will expire; 3) dozens of short-term tax breaks that Congress regularly renews would not be extended; 4) the 2-percentage point payroll tax cut would expire; 5) new taxes in the Affordable Care Act would take effect; and 6) millions would become subject to the alternative minimum tax if the so-called “patch,” which expired at the end of 2011, were not extended.

Now policymakers view these tax changes very differently. The Tax Policy Center has ranked the various tax changes in the order of their likelihood of occurring from the most likely to the least likely (see Table). The most likely increase is the expiration of the payroll tax, since neither presidential candidate has proposed any extension. That coincides perfectly with my view that extending the payroll tax cut endangers the future of the Social Security program. At the other extreme, President Obama is committed to extending the Bush tax cuts for those with household income below $250,000.

My view is that the additional money from all expiring tax provisions will be needed to reduce the deficit, and it will all materialize if nothing is done. The effect would be quite progressive. Taxes for households in the middle of the income distribution would increase by $1,984 on average and for those in the top 1 percent by $120,537. One thing the Congress has demonstrated over the last several years is that it is very capable of doing nothing. Doing nothing may be the only way to introduce taxes into the mix of policies to reduce the deficit. The Congressional Budget Office estimates that if both the tax increases and scheduled spending cuts took effect, the economy would contract at an annual rate of 1.3 percent in the first half of 2013 and grow by 2.3 percent in the second half. After all we have been through, no one wants to see negative growth. But at least on the tax side, some pain in the short term would produce a balanced package of taxes and program cuts, create enough revenues for meaningful tax reform, and set the stage for a much brighter deficit outlook for the long term.