Married Women More at Risk in Retirement Than Singles

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Despite having more income and assets, two-earner couples benefit less from Social Security and save too little in 401(k)s.

Women today will spend about half of their adult years on their own. They are more likely not to marry; when they do marry, they do it later; and they are more likely to divorce. Therefore, it is important to understand the differential risk women approaching retirement face based on their marital histories

A recent study used the National Retirement Risk Index (NRRI) to assess the retirement security of women in their 50s. The NRRI is calculated by comparing households’ projected replacement rates – retirement income as a percentage of pre-retirement income – with target replacement rates that would allow them to maintain their standard of living. Those falling short are considered “at risk.”

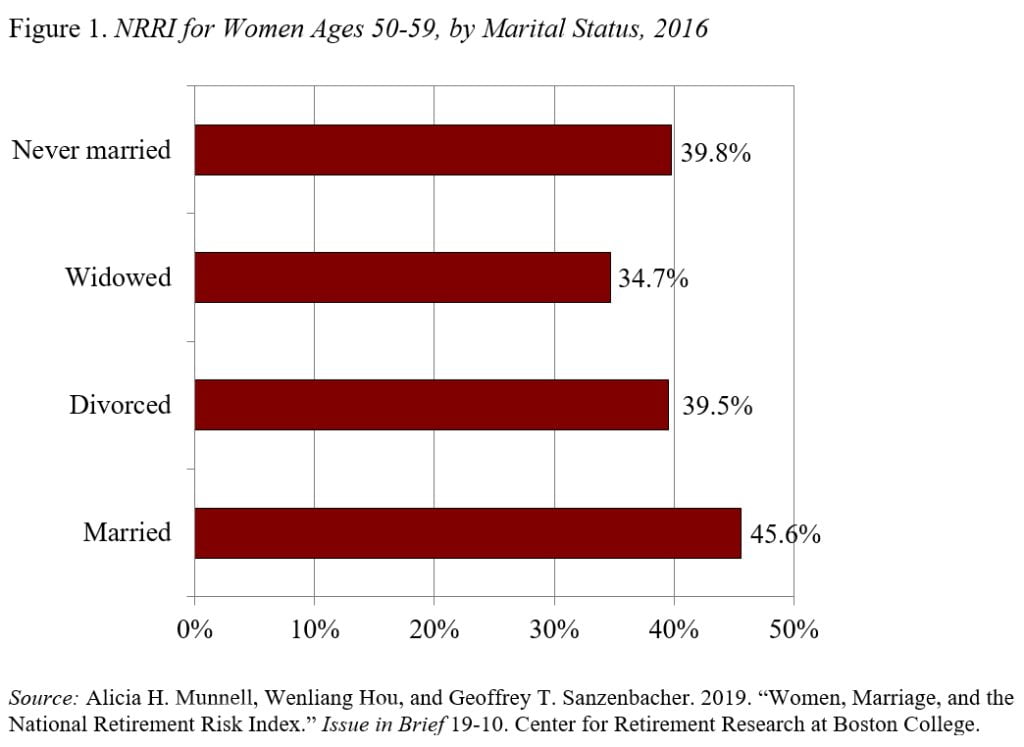

The Survey of Consumer Finances, which underlies the NRRI, provides a lot of information about the economic status of women. As expected, married women are better off than single women. Their households have higher earnings, greater financial assets, more home equity, greater assets in a defined contribution plan, and are more likely to be covered by a defined benefit plan. Yes, married households have the advantage of two potential earners and savers, but – for each earnings and asset measure – single women have much less than half the resources of married couples. Given the much stronger economic position of married women, one might expect that they are less likely to be at risk in retirement than single women. It turns out, however, that the NRRI is higher – that is, a greater percentage of households are at risk – for married women than for single women (see Figure 1). Married women show 46 percent at risk compared to about 39 percent, on average, for all single women.

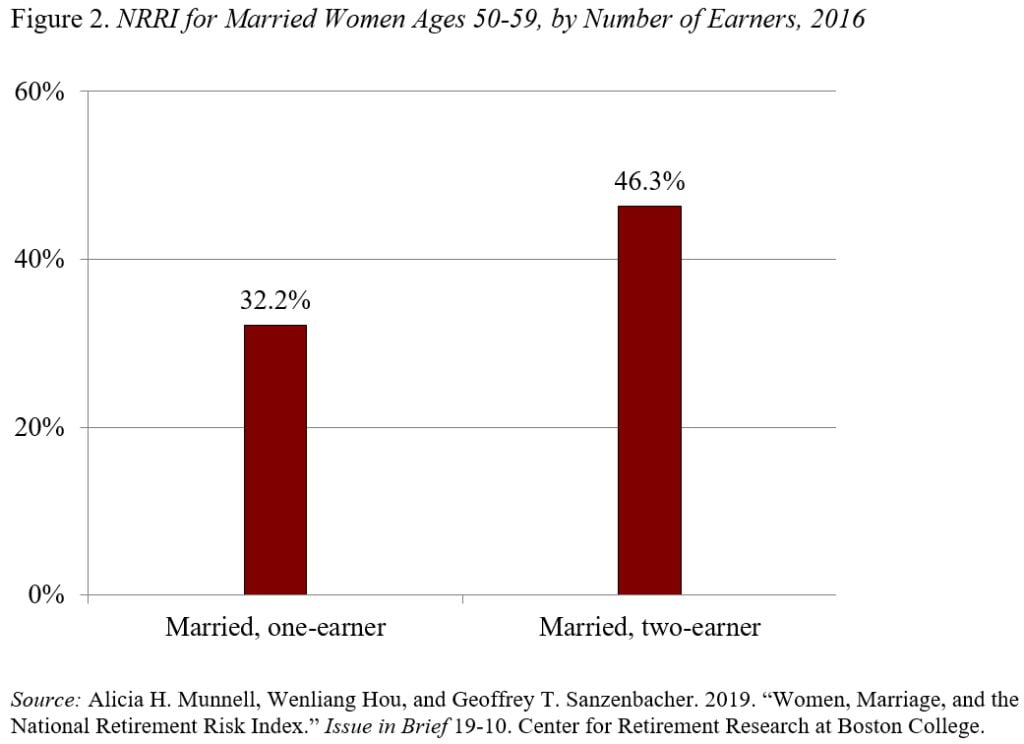

Why such a counterintuitive finding? The answer hinges on the outcome for two-earner couples, who have a much higher percentage at risk than their one-earner counterparts (see Figure 2).

The number of earners in a household affects the outcome in two ways. The first is through the Social Security system. Social Security provides a non-working spouse a benefit equal to 50 percent of the worker’s benefit. If the second spouse goes to work, the spousal benefit gradually declines and disappears completely when the second spouse’s worker benefit matches or exceeds the level of the spousal benefit. In addition, Social Security has a progressive benefit formula that provides a higher benefit relative to earnings for lower earners. Given that one-earner couples earn less than two-earner couples, they gain from this progressivity.

The second way in which two-earner couples get in trouble is that they tend to undersave in their retirement plans. The problem arises because in about half of two-earner couples only one of the earners is covered by an employer retirement plan. A recent study showed that the covered workers in this situation do not increase their contributions to compensate for the fact that their spouse is not saving, so that the contribution rate for couples with a single saver was only about half of that for two-earner, two-saver couples.

These findings highlight the need for two-earner couples to save more, and the best way to address this issue would to broaden access to retirement savings plans in the workplace. In addition, plan sponsors could help educate their married workers about the potential need to save for two.