Expanded Child Tax Credit Helped Black Families

The drop in a key poverty measure to a historic low was an immediate result of Congress increasing the child tax credit in 2021 to make more families eligible and help them cope with COVID-19.

The policy was particularly effective in reducing poverty in the Black community, according to researchers at Howard University, the University of Alabama, and the University of Wisconsin.

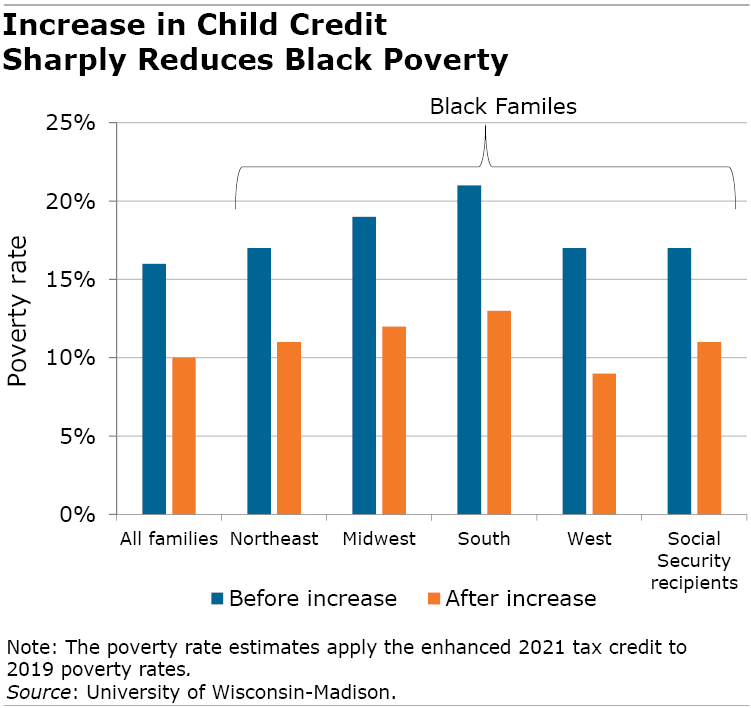

Black Americans’ poverty rate has always been much higher than the White rate. But the researchers show that the effect of a more generous child tax credit was to dramatically reduce Black poverty all over the country. They overlaid the larger tax credit amounts and the expanded eligibility onto families’ 2019 financial data to estimate how many families rose above the poverty line in 2021.

In the West, for example, increasing the credit and expanding eligibility would cause poverty to fall almost in half, from 17 percent of Black households in 2019 to 9 percent in 2021. The White poverty rate in the western states would fall by a third.

And in the South, home to more than half of the country’s Black population, the credit would cut poverty from 21 percent to 13 percent – nearly 40 percent, compared with a 30 percent decline in southern White households.

Congress raised the annual child tax credit in 2021 from $2,000 to $3,600 per child under age 6 and to $3,000 for older kids and teenagers as part of the American Rescue Plan during COVID. The credit was also extended to very low-income families that don’t file a federal tax return and were previously ineligible. The enhancements expired at the end of 2021.

Black families got a bigger boost from the tax credit because the increase was larger relative to their incomes, which are lower than other families’ incomes, and because Black families were less likely to be eligible prior to the 2021 enhancements.

The researchers’ estimates also showed large reductions in poverty among the 12 percent of low-income families receiving some type of Social Security benefit, including a 59 percent drop for very disadvantaged families in the Supplemental Security Income program.

Another reason for the outsized impact is that Black families are more likely to be multigenerational with a grandparent on Social Security who uses the monthly check to help support the grandchildren. A single parent may also live with them, but the families tend to be more impoverished than other families with children, making many of them ineligible for the child credit. In 2021, when the credit was extended to grandfamilies that don’t file returns, their estimated poverty rate fell by nearly half, from 14 percent to 8 percent.

To gauge the law’s impact on poverty, the researchers used two national data sets containing details on U.S. households, such as their race, how many children are present, family income, and whether anyone gets Social Security benefits. They assumed that 100 percent of all eligible children received the credit, which is higher than recent estimates showing that take-up was closer to 75 percent.

They measured poverty using the Supplemental Poverty Measure, or SPM, which captures a full picture of a family’s standard of living by taking into account more than just cash income. The SPM includes government food and housing subsidies and subtracts the amount families spend on items like taxes and medical care.

The enhanced child tax credits have ended. But the researchers hope that showing how they helped disadvantaged families will encourage government agencies to reach out and enroll more families who are eligible now but are slipping through the cracks.

To read this study by Jevay Grooms, Madelaine L’Esperance, and Timothy Smeeding, see “Social Security Interactions with Child Tax Credit.”

The research reported herein was derived in whole or in part from research activities performed pursuant to a grant from the U.S. Social Security Administration (SSA) funded as part of the Retirement and Disability Research Consortium. The opinions and conclusions expressed are solely those of the authors and do not represent the opinions or policy of SSA, any agency of the federal government, or Boston College. Neither the United States Government nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, make any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of the contents of this report. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise does not necessarily constitute or imply endorsement, recommendation or favoring by the United States Government or any agency thereof.