Multiemployer Plans Can’t Cut Their Way to Solvency

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Select committee faces November deadline to propose a solution.

Policymakers in Washington are hard at work trying to find a solution to the multiemployer plan crisis. A solution is essential because multiemployer plans pay relatively low benefits to relatively low-paid workers. Without these benefits, many would be destitute.

The focus of current efforts is the bi-partisan House and Senate Joint Select Committee on Solvency of Multiemployer Pension Plans. This committee – co-chaired by Sen. Orrin Hatch (R-UT) and Sen. Sherrod Brown (D-OH) – is charged with producing a bill by November 30. A new approach is desperately needed because the most recent legislative initiative to address the multiemployer problem – the Multiemployer Pension Reform Act of 2014 (MPRA) – has not turned out to be a solution.

As a reminder, multiemployer plans are defined benefit plans created by collective bargaining agreements between a labor union and two or more employers and typically exist in industries with many small employers – employers that would not ordinarily establish a defined benefit plan on their own. While the majority of multiemployer plans have returned to financial health since the financial crisis, a substantial minority – covering about one million of the 10 million participants – face serious funding problems and could run out of money within the next 15-20 years. Additionally, the Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation (PBGC) – the backstop for defunct plans – expects its multiemployer insurance program to run out of money within 10 years.

MPRA allowed plans facing impending insolvency to cut accrued benefits if approved by the Treasury. The notion was that spreading the pain could produce a more equitable outcome than paying full benefits until the money ran out and then leaving retirees with no benefits at all. A key criterion for approving MPRA cuts, however, is that the plan must be sustainable once the cuts are made.

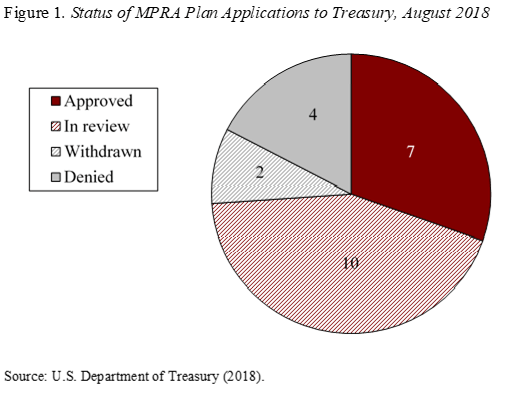

My colleague Caroline Crawford has been keeping tabs on the status of Treasury applications. As of August 2018, 23 multiemployer plans have applied to the Treasury to cut benefits under MPRA. As shown in Figure 1, seven applications have been approved, ten are under review, two have been withdrawn, and four have been denied – including that of the very large Central States Teamsters plan.

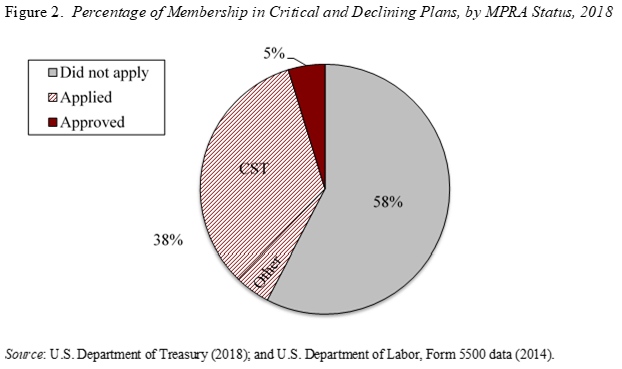

Including the most recent flurry of activity, 30 percent of all MPRA applications have been approved – up from only about a quarter in 2017. At first glance, this statistic suggests that MPRA has been successful. However, most of these approved plans are very small and represent only 5 percent of members in critical-and-declining plans (see Figure 2). And the potential impact of MPRA remains limited as the ten applications currently under review are also small plans.

MPRA has taught us that plans cannot cut their way to solvency. Another solution is needed, and fast. Government loans seem like a logical approach for these plans facing an impending cash-flow crisis. Let’s hope that the Joint Select Committee can agree on a proposal.