Should the 47 Percent Pay Income Taxes? Families with Children

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

As many commentators have pointed out, the main reasons that 47 percent of households do not pay federal income taxes are provisions in the tax code that 1) provide basic exemptions for subsistence level income; and 2) offer tax expenditures that wipe out a household’s tax liabilities or provide refundable credits. These provisions mainly benefit senior citizens and low-income families with children. These two groups account for the bulk of the non-tax paying units. The implication of some of the discussion is that the country would be better off if these provisions were changed and more units paid taxes. Is that true? This piece takes a brief look at the tax treatment of low-income families with children. The next BLOG looks at the provisions for retirees.

Low-income families with children, like other households, are eligible for the standard deduction and personal exemptions. These provisions are designed to exempt subsistence levels of income from tax and to adjust for differences in ability to pay by family size. For a head of household in 2012, the standard deduction is $8,700. The personal exemption is $3,800. So a mother with two children would have zero taxable income with an income of $20,100. Is that too high or too low? My view is that, given that the 2011 poverty threshold is $18,123 for a family of three, it seems about right. But you can judge for yourself.

In addition to the basic provisions, low-income households with children also benefit from three tax expenditures: the child tax credit, the child and dependent care tax credit and the earned income tax credit.

Payroll tax rates have increased since the early 1980s, but these increases have not produced a more regressive federal tax structure. The reason is that the growth of the payroll tax has been accompanied by a major expansion in the Earned Income Tax Credit. This provision, which was originally introduced in 1975, actually began as a modest attempt to reduce the regressive effects of a rising payroll tax (Holt, 2006). The credit was made permanent in 1978 and expanded significantly in 1986. It was expanded again in 1990 and, in 1993, President Clinton and Congress doubled its size to ensure that full-time minimum wage workers would not live in poverty.

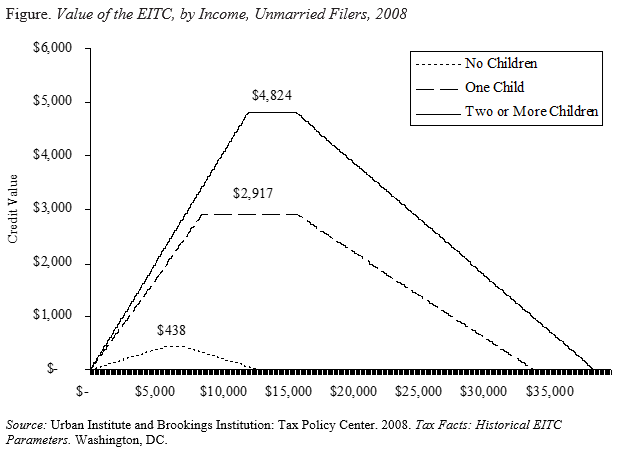

The federal EITC comprises a series of credits that operate differently for different types of families. All share a common formula, however. The formula increases the credit for each dollar of earnings up to a certain level; maintains the maximum credit through an amount of additional earnings; and then gradually phases out the credit at higher incomes. Most importantly, the EITC is refundable, which means that even those who have no taxable income under the federal income tax will receive a check. For example, in 2008, a worker with two children could claim a maximum credit of $4,824, with the credit phased out at $38,646 (see Figure).

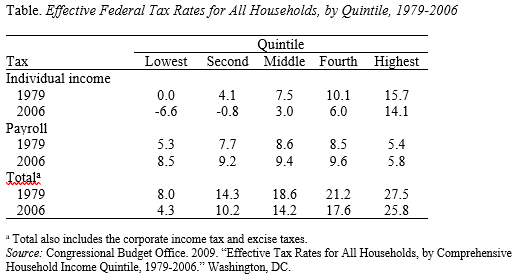

The EITC has served to more than offset the increasing payroll tax rates (see Table). Between 1979 and 2005, the total effective tax rate on the bottom quintile has been cut in half and for the second quintile has been cut by about one third. In contrast, the effective tax rate on the top quintile has been virtually unchanged. Thus, while the EITC is not a modification to the payroll tax, it has substantially reduced the burden of that levy.

Without a substantial increase in the EITC, which could create problems of its own, a substantial increase in payroll tax rates to restore Social Security’s solvency could put low-income workers at risk. Therefore, it is imprudent to rely on the payroll tax any more than necessary.

Furthermore, the legacy costs associated with the start-up of the Social Security program provide a logical reason to transfer some of the burden of financing Social Security from the payroll tax to general revenues.