State Retirement Program Initiatives and the Saver’s Credit

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

The Saver’s Credit could enrich state retirement programs for uncovered workers.

The “Saver’s Credit” has come up a couple of times in the context of state initiatives to establish state-run retirement plans for uncovered workers. In theory, the Saver’s Credit could serve as a government matching contribution that would enhance the impact of the new plans. This notion is certainly worth exploring, although the current design of the Saver’s Credit will limit its effectiveness.

The Saver’s Credit gives a special tax break to low- and moderate-income taxpayers who are saving for retirement. It was introduced in 2001 and scheduled to expire in 2006. The Pension Protection Act of 2006, however, made the credit permanent and indexed the income thresholds.

The Saver’s Credit is in addition to other tax benefits for saving in a retirement account.

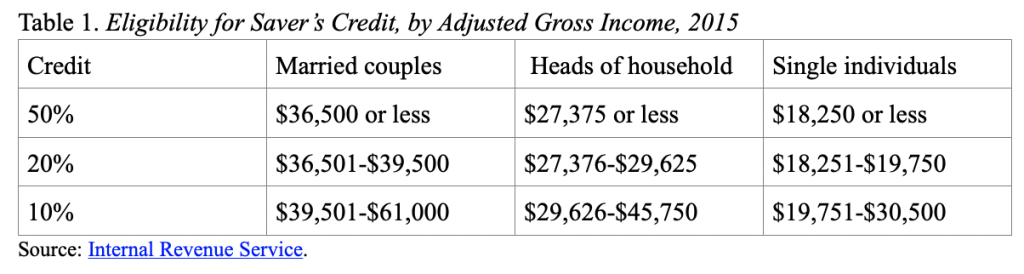

Depending on adjusted gross income (AGI), an eligible taxpayer can claim a credit for 50 percent, 20 percent, or 10 percent of the first $2,000 contributed during the year to a retirement account. Thus, the maximum credit is $1,000 for an individual (.50 x $2,000) and $2,000 for a married couple when each is contributing to a plan. Table 1 shows the 2015 AGI limits for married couples, heads of households, and single individuals.

In theory, the Saver’s Credit looks great. For example, assume each member of a married couple with a combined AGI of $35,000 contributes $1,000 to an Individual Retirement Account (IRA) – for a total household contribution of $2,000 – under the new programs being designed in Connecticut or California. This couple is eligible for a $1,000 credit (.50 x $2,000). That is, they pay $1,000 less in federal income taxes than they would have otherwise. The net result is a $2,000 account balance that cost the couple only $1,000 after taxes (the $2,000 contribution minus the $1,000 credit), which is equivalent to a 100-percent match on the contribution.

The problem is the Saver’s Credit does not work as smoothly as suggested above. The first issue is that the credit is non-refundable. Non-refundable means that the credit can reduce the required tax repayment to zero but not below. So if the couple only had a tax liability of $750, their credit would be limited to that amount. Second, the Saver’s Credit is often not usable for taxpayers with children who receive the Child Tax Credit; since both credits are non-refundable, the Child Tax Credit can reduce their tax liability enough to crowd out the Saver’s Credit. Finally, many people do not know about the Saver’s Credit; a 2005 study in the National Tax Journal found that qualified taxpayers were 70 percent more likely to claim the Saver’s Credit if they had their taxes figured by a professional preparer or with computer software.

Just as an aside, the design looks a little crazy. As couples move from an AGI of $36,500 to $36,501, their credit rate drops from 50 percent to 20 percent. This drop means that the maximum credit for a $2000 contribution drops from $1,000 to $400. While it makes sense for the credit rate to decline as income rises, the phase-out could be structured more gradually.

So, if I were in charge, I would make the Saver’s Credit refundable, raise the income limits for eligibility to apply to more middle-class households (the median income of the uncovered worker in Connecticut is $43,000), and make the phase-out more gradual. Since the point of the Saver’s Credit is to encourage retirement saving, I might even have the refundable payment automatically deposited into the saver’s IRA.

Even in its flawed condition, however, the Saver’s Credit is helpful. So states initiating retirement programs for their uncovered workers should encourage their new savers to take advantage of it.