Subprime Crisis Lingers for Minorities

As Americans were riveted to the spectacle of teetering Wall Street behemoths in 2008, another ruinous tragedy was beginning to unfold: a national foreclosure crisis.

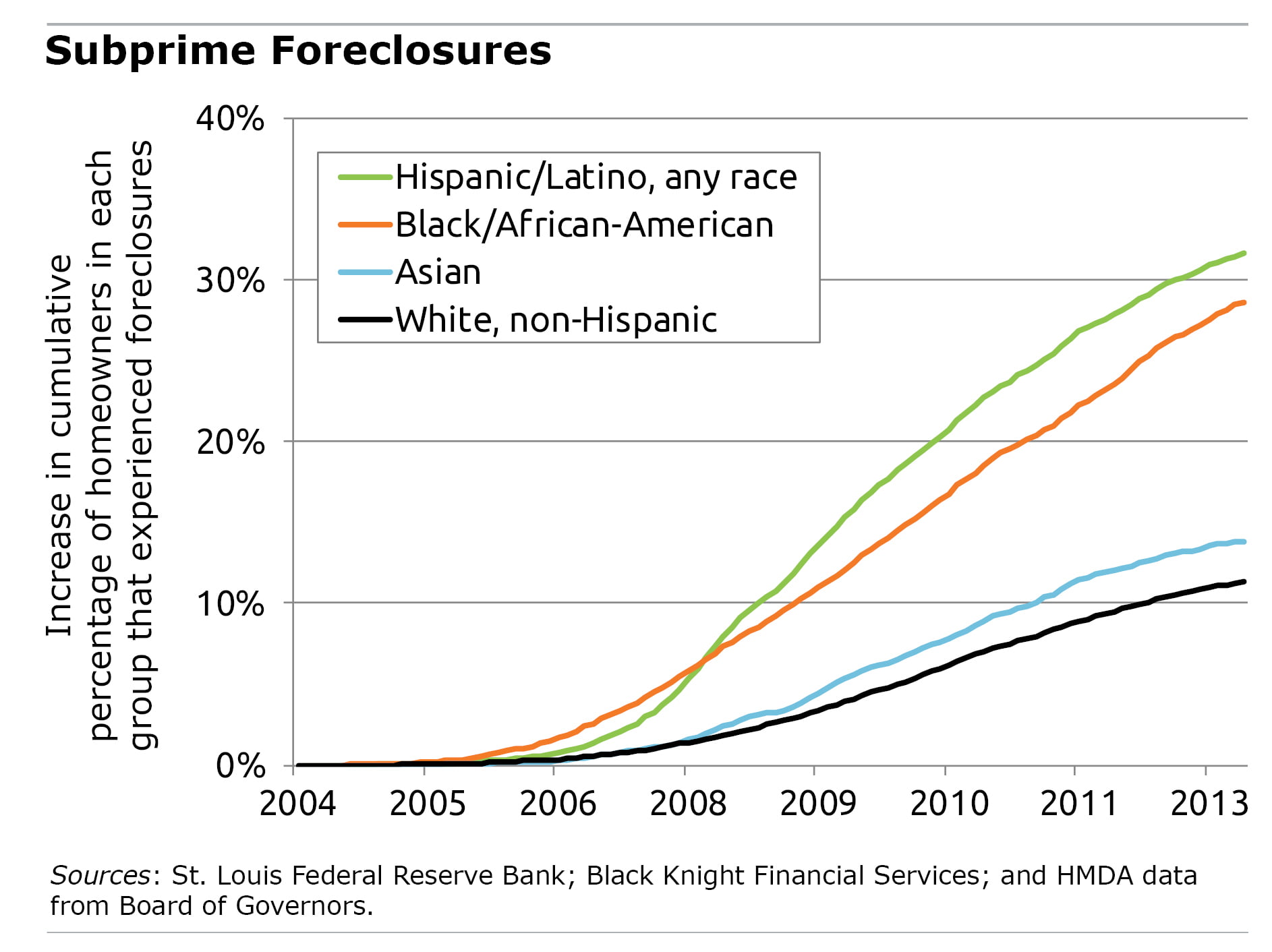

Black and Hispanic homebuyers were hit hardest by the foreclosures that resulted from unbridled sales of predatory subprime mortgages, which exceeded $500 billion annually at the market’s peak.

Black and Hispanic homebuyers were hit hardest by the foreclosures that resulted from unbridled sales of predatory subprime mortgages, which exceeded $500 billion annually at the market’s peak.

In the decade since the financial crisis, the stock market has rebounded smartly, but the damage to minority communities remains. At the height of the foreclosure crisis, entire neighborhoods were littered with bank foreclosure sales and realtors’ signs advertising sales of the properties.

About 30 percent of black and Hispanic borrowers’ homes in total have gone into foreclosure in the years since the housing market crash, compared with 11 percent of whites’ homes.

“For [minority] families, financially destructive foreclosure events delayed and potentially derailed the dream of homeownership,” the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis concluded in a report on the continuing impact of the financial crisis.

But the damage goes deeper than that. Because home equity is often the most valuable asset that people own, the foreclosure crisis “severely damaged the balance sheets of minority families,” the Fed said.

The 2008-2009 recession and housing market crash caused foreclosures to spike to historic highs for two reasons. First, millions of unemployed borrowers could no longer afford their subprime mortgages, which featured a spike in payments after the second year of the loans. Second, homeowners often found that they could not make the additional equity payments lenders were demanding when a house’s value dropped below its mortgage value – in other words, when borrowers found themselves “underwater.”

Today, homeownership rates are hovering at the low levels last seen in the 1990s. In 2016, the latest year of available data, the African-American homeownership rate was 42 percent, and Hispanics’ rate was 46 percent. White homeownership, which also declined after the housing market crash, is 68 percent.

Minority homeowners bore the brunt of the crash, because subprime mortgage brokers frequently targeted their communities, where it had historically been difficult to get a loan.

ComplianceTech, a banking software company, estimates that more than half of all black homebuyers used subprime loans to purchase a house in 2006, and 41 percent of Hispanic buyers received the loans. In contrast, just 22 percent of whites financed their home purchases with subprime loans.

One researcher found that Boston brokers disproportionately sold subprime mortgages even to high-income blacks and Hispanics, whose credit ratings should have qualified them for the same traditional 30-year mortgages available to white homebuyers with similar incomes.

There is growing concern that the housing market may now be in the midst of another bubble. A look back at the subprime mortgage crisis and resulting foreclosures is a reminder of the damage caused when a bubble pops.

Squared Away writer Kim Blanton invites you to follow us on Twitter @SquaredAwayBC. To stay current on our blog, please join our free email list. You’ll receive just one email each week – with links to the two new posts for that week – when you sign up here.

Comments are closed.

Well, at least a (very) loose connection made between the circumstances of those still feeling the effects of the subprime crisis and those who subprime lending was intended for: https://mobile.nytimes.com/1999/09/30/business/fannie-mae-eases-credit-to-aid-mortgage-lending.html

Nevertheless, those consumers who took subprime mortgages should have known better.

‘Should have known better” presumes the borrowers possessed an understanding of the risks involved in subprime lending vs. other more traditional formats. Shoulda, woulda, coulda presumes this information was known to borrowers, provided in understandable terms by responsible lenders-real estate agents- and/or developers. And that was not the reality.