Suspending the RMD Rules for 2020 Is a Good Move

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Why RMDs are important – we do not want to force sales of depressed assets.

The current Required Minimum Distribution (RMD) rules are a useful tool to ensure that the favorable tax provisions associated with retirement plans are used to generate retirement income – not to enhance the size of estates. But given the current collapse of financial markets, Congress was right to suspend the RMD for 2020 as part of the recent CARES Act. This decision is one key step in protecting the savings of older Americans.

Under current law, holders of 401(k)s and traditional Individual Retirement Accounts (IRAs) are required to withdraw a percentage of their account balances each year once they reach 72 (formerly 70½). This requirement assures that the money in these tax-favored saving accounts is used to provide income during retirement rather than to pass on wealth to heirs. The RMD is calculated so as to spread balances over the participants’ remaining lives. The penalty for failure to take an RMD is draconian – 50 percent of the amount that should have been withdrawn.

As I said, the intent of the RMD seems sensible to me. The Treasury forgoes tax revenues to encourage retirement saving; the balances in the retirement accounts should be used for this purpose. I don’t want to have to pay higher taxes so rich people can leave bigger estates. The RMD rules are not designed to force full depletion of the account. Calculations show that assuming the retiree earns 4 percent returns, over 70 percent of the original account balance remains at age 90.

That said, if I were in charge, I would make two changes to the RMDs:

- Exempt holders of small account balances. The median 401(k)/IRA balance for working households with a 401(k) approaching retirement was $135,000 in 2016. Make a rule that households with total retirement account assets, at age 72, of less than $250,000 (indexed for inflation) are exempt from the RMD requirements.

- Make the penalty less draconian. A 50-percent tax penalty is dramatically out of line with other penalties in the retirement account system. Perhaps, reduce it to 10 percent.

But the topic here is not reform but rather a temporary suspension. The suspension that was just enacted has been done by Congress before – in 2009 – so that people would not be forced to cash in severely depressed assets in the wake of the 2007-09 financial crisis.

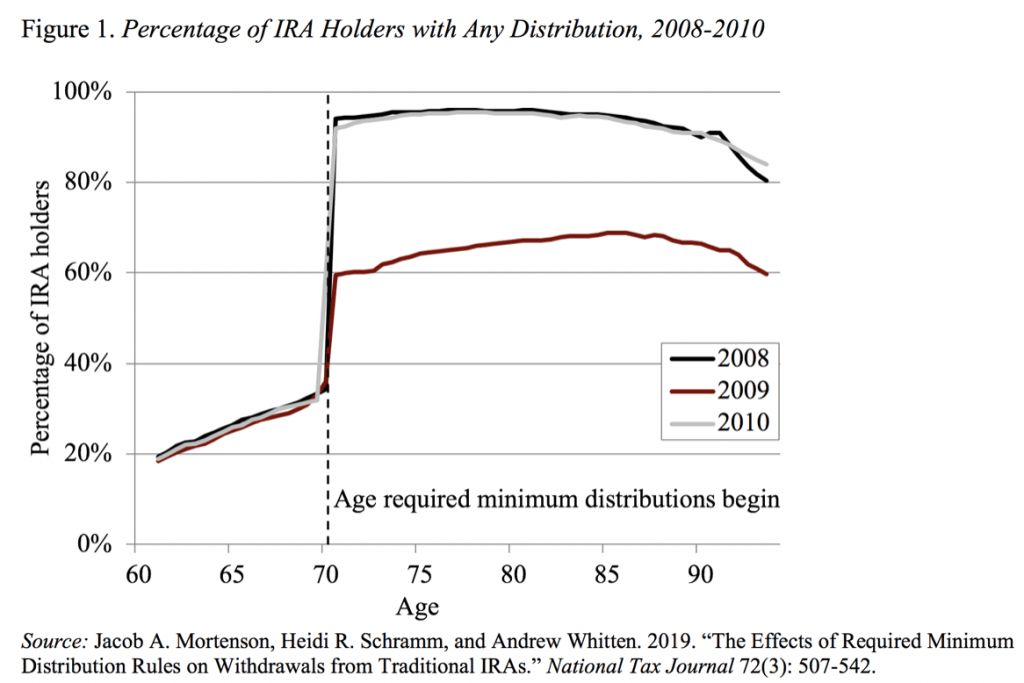

In fact, the 2009 suspension played a key role in a recent paper to determine the extent to which the RMD rules are binding – that is, force people to do something they would not do otherwise. The researchers used data from the tax returns of 1.8 million IRA holders in 2000-2013, but the most interesting part of the paper is the raw data on the percentage of IRA holders with any distribution for the years 2008-10 (see Figure 1). The data show that, while only about 25 percent of individuals younger than 70½ took an IRA distribution, that figure jumps to about 90 percent once the RMD kicks in. When the RMD was suspended in 2009, the percentage taking any distribution dropped from the 90-percent range to 60 percent. It’s unclear why it didn’t drop all the way back to 25 percent – perhaps some people didn’t realize they did not have to take an RMD, and perhaps some people simply needed the money.

In the current context, the data from 2009 show that many people will take advantage of the RMD suspension for 2020. Not being forced to sell seriously depressed assets at the bottom of the market will increase the prospects for many to have a more secure retirement.

I realize that the RMD suspension is a small change in the current environment, but it will definitely help millions of older Americans.