The Saga of Company Stock in 401(k) Plans – Some Problems Solve Themselves

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Holding company stock in 401(k) plans – always a bad idea – has declined sharply.

When a colleague and I wrote a book on 401(k) plans in 2004, we devoted a whole chapter to the perils of investing 401(k) assets in company stock. And many meetings around that time involved impassioned pleas for Congress to limit company stock investment. At one of these meetings, someone suggested that the company stock problem may be one that would solve itself, as target date funds became the default – diverting employees’ attention from the stock of their employers.

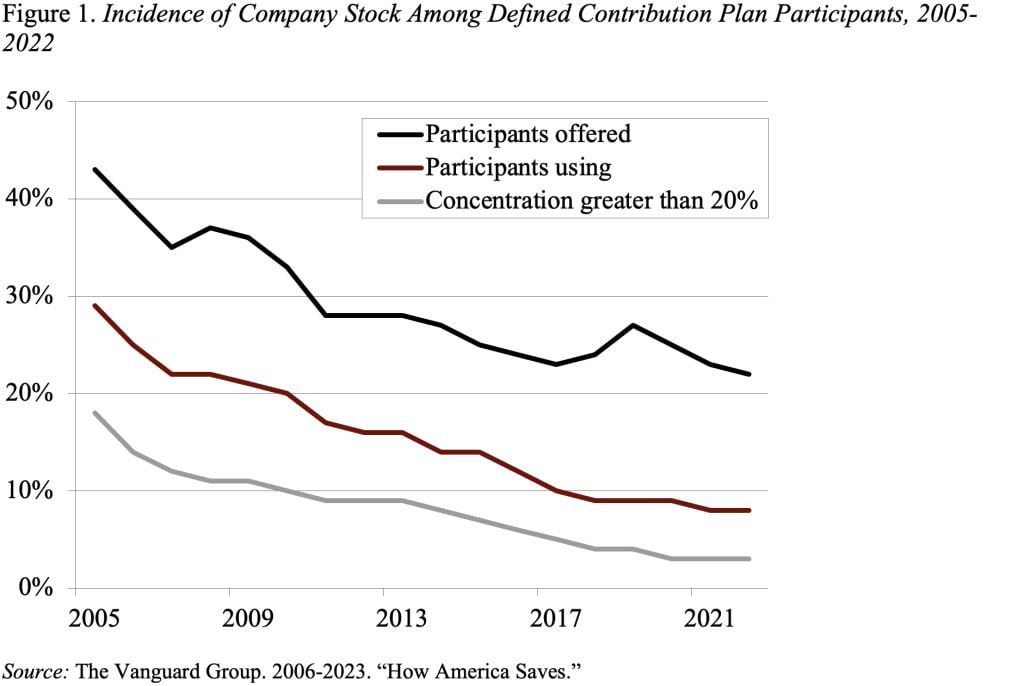

Indeed, Vanguard data show that this “squeezing-out” phenomenon, combined with sponsor recognition of the risks of single-stock investment, has resulted in a big decline in both the percentage of plan sponsors actively offering company stock – from 12 percent in 2005 to 8 percent in 2022 – and the percentage of participants with company stock. The decline in participants has been particularly dramatic: the percentage offered company stock has dropped from 43 percent to 22 percent, the percentage holding company stock from 29 percent to 8 percent, and the percentage with concentrations of company stock over 20 percent from 18 percent to 3 percent (see Figure 1).

Overall, three factors have contributed to the decline. First, target date funds have increased dramatically in popularity, so that – when combined with equity index funds – they now account for almost 80 percent of defined contribution plan assets. Second, sponsors have come to realize that having their employees invested in company stock is risky for both parties – think Enron. As a result, a 2020 Vanguard study found that more than half of companies that had previously offered company stock no longer do, and the bulk that do offer it permit immediate diversification. Third – probably less important given employee inertia – the Pension Protection Act of 2006 expanded diversification rights for participants so that they could sell their own company stock at any time and employer contributions of company stock after three years.

While these factors have led to a dramatic decline in company stock, 3 percent of participants still hold more than 20 percent of their assets in it. That’s not good. Holding one stock – instead of, say, thirty – more than doubles the riskiness of a portfolio, with no potential offset of higher returns. Moreover, participants with company stock own an asset whose value is closely correlated with their earnings; if the company gets into trouble, they risk losing not only their job but also their retirement saving.

So, why do participants hold company stock? Generally, they are not sophisticated investors and underestimate the risk of investing in a single stock. Employees also like to buy what they know; they see executives getting rich and want to have a chance to swing for the fences. The problem is exacerbated when the employer matches in company stock, which is often treated as an endorsement of the purchase. Historically, employers have strongly valued the ability to match in stock rather than cash, apparently because it allowed them to hang onto their valuable cash reserves. This preference, however, may have been diluted by a series of lawsuits over the last 15 years.

The problem of excessive company stock holdings does not arise with defined benefit plans, because ERISA permits no more than 10 percent of plan assets to be held in company stock. When I was young, I would push for that limit for defined contribution plans. But given our crazy world, that fight is pretty low on my to-do list. Let’s simply rejoice in the progress made to date.