The Shrinking Middle and Shrinking Wages

My husband likes to tell a story about his father, Joseph Virchick, who was a pipefitter for the Standard Oil refinery in Bayonne, New Jersey, starting in the 1950s. It was a union job – the Teamsters – paying solid middle-class wages that supported his family in an upscale Levitt development with its own swimming pool.

The point here is that this pipefitter with a high school degree lived about as well as his college-educated neighbors who commuted into nearby Manhattan. Virchick and his wife, Henrietta, who also worked, sent all three kids to college. When he retired in the 1980s, they had a pipefitter’s pension to supplement their Social Security.

Today, only 6 percent of private-sector workers are unionized. Something else is going by the wayside along with unions and company pensions: a thriving middle class.

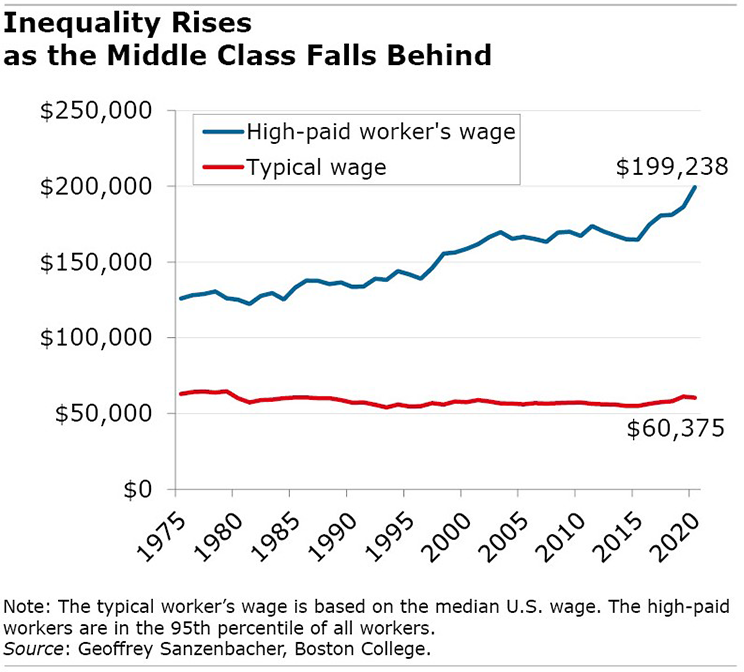

Boston College economist Geoffrey Sanzenbacher argues in his new book that while the U.S. economy, on a per capita basis, has more than doubled in size since 1975, the typical middle-class man’s income, adjusted for inflation, has shrunk by about $2,500, to $60,375 in 2020. (He tracked men’s wages, because the story about women, who flooded into colleges and into the labor force more recently than men, is messier.)

“During a four-decade stretch, middle-class workers lost ground,” Sanzenbacher writes in “The Six Facts that Matter: Understanding Inequality in the United States.”

The same powerful forces that have caused regular workers’ wages to decline also fueled the widening disparities between middle- and lower-paid workers and the people at the top, whose pay has increased since the 1970s. To be sure, lower-paid workers have gained back some of that ground since the pandemic began, and their wages have risen faster than higher-income workers’ pay. But the large inequities persist.

Sanzenbacher blames two things for the eroding middle class: globalization and technology.

Globalization is now a familiar issue. Why pay a pipefitter, garment worker, or autoworker a livable wage when a lower-paid worker in a less developed country will do the same work for much less? The United States has lost millions of solid manufacturing jobs since the 1970s to places like China and Brazil, depressing U.S. wages, especially in manufacturing. At the same time this has been happening, the pay of so-called knowledge workers in this country has risen in industries like financial services and biotechnology to meet the demand for their products and services in overseas markets.

Technology’s impact is more nuanced. As companies adopt sophisticated robots, computers and other technologies, they need more well-paid, well-educated engineers, systems analysts, and mechanics who can interpret the data or operate the equipment on the factory floor. As the economy grows, companies also need more low-skilled workers who can do the jobs that computers can’t, like mopping floors. But there’s less need for the types of jobs that support the middle class.

To explain how this works, Sanzenbacher relies on another economist’s well-known example of a bank that processes checks for its retail customers. In the past, one middle-class worker did all five steps necessary to process the checks, from removing staples and stacking the checks in the same way so a machine could read them and add up the amounts to inspecting problem checks or checks written in very large amounts.

Technology entered the picture when banks purchased optical character recognition software for complex tasks like reconciling the amount on a check with the deposit slip, totaling the checks, and flagging discrepancies. And these computers made the high-paid bank executives more productive, which increased their pay even more. As the economy grew, banks also had to hire more low-paid workers for the simplest jobs – removing the staples and mopping the lobby.

The losers were the middle-class workers who used to do all five, fairly routine steps in check processing before the computers took over, Sanzenbacher explains. “These routine jobs – which were often middle-class – were often replaced with a combination of lower and higher paying jobs,” he said.

“In other words, technology has led to a “Polarization” of the job market, with the result being a decline in demand [for workers] in the middle of the income distribution.”

Rising U.S. inequality, political divisions along class lines, and talk of the fading American Dream – it can be argued that the backstory to these intractable issues is the shrinking middle class and the disappearance of jobs like bank clerks.

Squared Away writer Kim Blanton invites you to follow us on Twitter @SquaredAwayBC. To stay current on our blog, please join our free email list. You’ll receive just one email each week – with links to the two new posts for that week – when you sign up here. This blog is supported by the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Comments are closed.

The US is splitting into a very wealthy upper class who, through their political donations, dominate the government and get favorable tax treatment, and the rest of us. This leads to potential political upheaval as the lowest paid have had enough. Bring manufacturing home and see that the rich pay their fair share.

The problem with statements like “their fair share” is who gets to determine the “fair share. Approximately 57% of Americans don’t pay any federal income tax but receive subsidies through the tax system, which in effect are gifts from the 43% who do pay taxes. We already have a progressive tax system where the more you make the more you pay (in $ and as a % of income). The top 1% already pay 39% of total federal income tax.

Remember when Ross Perot, as a Presidential candidate, said if NAFTA would be passed “ there would be a giant sucking sound of middle-class jobs going to Mexico and Central America.” This was 1992. Thirty years later…

In 1975, I had recently graduated from high school, and my father was still working. There’s no question that on an inflation-adjusted basis, he was earning more than what I was at a similar age. What’s not accounted for in that analysis is that I have access to investments that my father didn’t have available. When I consider the assets I have that generate an income flow for me, then my annual income far exceeds that of my father at this similar age. When comparing our era to our parents’ era, we have to consider alternative income opportunities – other than wages – that we have access to that our fathers did not. There is no question that I am much, much better off financially than my father ever was.

Economic fairness is a strong argument for bringing manufacturing home.

Another argument is national security:

It is very dangerous to be dependent on too few sources of vital services or products. There might be floods, fires, earthquakes, tsunamis, political upheavals, the source making a mistake on technology or demand, evildoers, comet strikes, etc.

Far better to have a variety of sources both U.S. and foreign, competing with each other for employees as they try to make the best products and services at the best prices.

And everyone should have some ownership of industry and commerce, perhaps through ITRAs or 401(k)s, perhaps through co-ops, perhaps through small businesses.

The politics of the ‘middle’ class are absent entirely from this assessment. Unions were created by workers and leaders; the second generation workers did not engage with the reality that their lifestyle was at the sufferance of a few men in the boardroom and in the top corporate suite who focussed on breaking the union..via legal changes (Taft Hartley law; Reagan’s series of anti -worker laws etc) and cultural changes (HRM policies). The second gen workers didn’t pay attention; they rode free. The middle class is also a construction of free quality education through a college degree, something brought to an end by Reagan, then Bush 1, then Clinton as states no longer received what they needed to support State Universities. Last but not least healthcare, day care, decent hours of work legislation and so forth. Technical change is arguably more advanced in Sweden than in the US but their workforce continues to have a robust ‘middle’ class.

Did Sanzenbacher’s analysis of wages include the cost of benefits? I believe that the cost of employer-provided benefits, especially health care, has grown much faster than cash wages. Same (but affecting high-paid employees) if options and other equity incentives were excluded. Focusing only on wages could skew the results.