Vignettes Improve Social Security Savvy

There’s an informal rule in journalism: put too many numbers in an article, and readers will drop like flies. A similar phenomenon might also be at work when someone looks at a Social Security statement filled with numbers.

There’s an informal rule in journalism: put too many numbers in an article, and readers will drop like flies. A similar phenomenon might also be at work when someone looks at a Social Security statement filled with numbers.

The statement, which is intended to help workers plan for retirement, shows the size of the monthly benefit check increasing incrementally as the claiming age increases. Yet many people still choose to claim their benefits soon after becoming eligible at 62, which means smaller Social Security checks, possibly for decades.

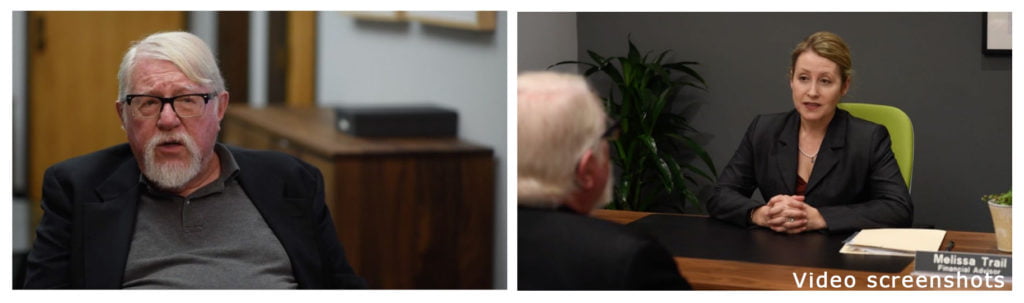

In a recent experiment, a friendlier approach proved effective in helping people process this information: tell a story. Researchers at the Center for Economic and Social Research at the University of Southern California created a fictional 3-minute video of a 62-year-old man talking with a financial adviser about retirement. The researchers showed it to workers between 50 and 60 years old.

Here’s one exchange in the video:

Adviser: [Social Security has] a tradeoff: you can decide to claim earlier. In that case, you would have a lower monthly benefit, but you’d get to enjoy these benefits for a longer period.

Worker: So if I claim sooner, I get less money per month?

Adviser: That’s right.

Later in the conversation, this concept starts sinking in. Instead of asking a question, the worker states a fact: [T]he monthly payments will be lower.

This non-numerical approach clearly had an impact. After seeing the video or reading the vignette on paper, the subjects accurately answered more than 90 percent of the true-false questions about Social Security’s mechanics, compared with just 78 percent accuracy by the people who didn’t see a vignette.

The results of this experiment, the study concluded, could help inform the Social Security Administration on how to “communicate these complex concepts to the public.”

To read the entire study, authored by Anya Samek, Arie Kapteyn, and Andrew Gray, see “Using Consequence Messaging to Improve Understanding of Social Security.”

The research reported herein was performed pursuant to a grant from the U.S. Social Security Administration (SSA) funded as part of the Retirement Research Consortium. The opinions and conclusions expressed are solely those of the author(s) and do not represent the opinions or policy of SSA or any agency of the federal government. Neither the United States Government nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of the contents of this report. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise does not necessarily constitute or imply endorsement, recommendation or favoring by the United States Government or any agency thereof.