What’s Happening to State and Local Government Finances?

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Revenue loss appears less than expected, but pension finances still may be affected.

In the process of trying to figure out how COVID and the ensuing recession have affected the retirement system, I had assumed that a large shortfall in state and local revenues would make it more difficult for governments to fund their defined benefit plans.

The first clue that things might not be quite as expected was a report from the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP) that concluded state revenues in 2020 (which ended in June for most states) were only about 2 percent below pre-pandemic projections. That’s much less than forecasters were projecting earlier in the year. It is also lower than the level suggested by the historical relationship between revenues and unemployment.

The reasons offered for this more modest decline are that the recession has been concentrated among the lower paid, who do not pay a lot in income or sales taxes; and federal aid boosted the purchasing power of these workers early in the pandemic.

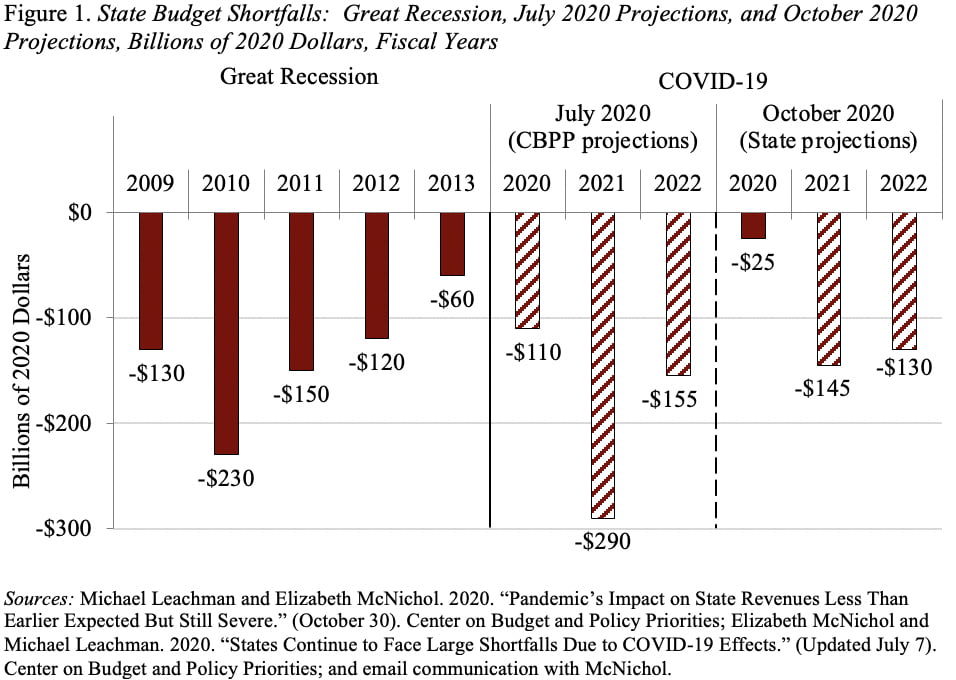

Beyond revenues, states face higher costs associated with the pandemic, including higher enrollment in Medicaid and other programs. According to the CBPP, even including these higher costs, states have grown more optimistic in the last several months and now project budget shortfalls of about $145 and $130 billion, respectively, for fiscal years 2021 and 2022 (see Figure 1). These numbers are down from the July projections of about $290 billion and $155 billion for the same years. All of these numbers include federal aid. Local governments also face some shortfalls, but less than the states because they rely on the property tax, which so far has been fairly stable.

Now along comes an interesting paper from Brookings with a nice updated summary by Louise Sheiner – thank god given the underlying paper is 98 pages! The question addressed by the Brookings team is “Why is state and local employment falling faster than revenue?” In the original paper, they started with the notion that revenues losses should be more modest this time around, because employment losses have been concentrated among the lower paid; the stock market has risen, which drives capital gains receipts; and the CARES Act provided unprecedented stimulus. Of course, states did see big declines in fees and taxes on airport use, gasoline sales, mass transit, etc. But they still anticipated only moderate revenue losses.

It turns out that the Brookings group now believes that even their original moderate loss projections were too high. Like the CBPP, the Brookings team projects revenue declines will be much smaller – and less persistent – than those experienced during the Great Recession.

Despite the modest revenue shortfalls, state and local employment has declined much more than during the Great Recession. Also, the composition of the cuts is different. In the Great Recession, state governments increased employment in education, while they cut employment elsewhere. Just the reverse is true this time around. At the local level, employment declines have been somewhat larger in education than non-education, whereas they were quite similar during the Great Recession.

The Brookings team offers two explanations for the large loss in education employment. First, the virus shut down schools and universities, which meant schools needed fewer bus drivers and cafeteria workers as well as fewer staff. Second, when the economy shut down, states – fearing big drops in revenue – likely cut aid for local education. Indeed, local education employment declined more in states with larger projected revenue declines. Interestingly, the researchers found no relationship between their measure of fiscal conditions and state and local employment outside of local education.

The bottom line of all this is that states and localities may not be under as much fiscal pressure as originally thought. Nevertheless, they still face budgetary shortfalls, which would have been even larger without federal aid. Overall, these fiscal pressures will make it more difficult for them to fund their pensions. In addition, with cuts in employment, payrolls will be smaller, so a contribution rate based on previous larger payrolls will be inadequate and will need to be increased.