While the Annual Fertility Rate Plummets, Lifetime Fertility Climbs

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Delayed motherhood is offset by more never-married women having babies.

I am fascinated by fertility patterns and was delighted to see the most recent piece from the Pew Research Center that helps reconcile the divergent trends shown by the annual fertility rate and the completed fertility rate. The annual fertility rate – number of births relative to the number of women 15-44 – is at an all-time low; the completed fertility rate – the total number of births by women age 40-44 – is higher today than it was in 1994, over 20 years ago.

These divergent patterns can be explained by two patterns: 1) women are having babies later in life, but 2) more women are deciding to become mothers and mothers are having more babies.

The median age at which women become mothers has increased from 23 in 1994 to 26 in 2014. This change has been driven in part by short-term factors such declines in births to teens and the Great Recession and in part by longer trends in educational attainment, labor force participation, and delays in marriage. The postponement in births helps to explain the decline in the current birth rate.

But this increase in later births has not resulted in lower lifetime fertility. One factor contributing to this outcome is an increase in motherhood among never-married women.

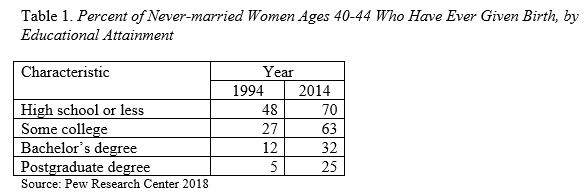

While the share of women at the end of their childbearing years who have never married rose from 9 percent in 1994 to 15 percent in 2014, the majority (55 percent) had at least one child in 2014 compared to less than a third (31 percent) in 1994. This pattern occurred across all educational groups.

The share of women who have ever been married and had children remained roughly constant (90 percent in 2014 versus 88 percent in 1994).

The big question is whether the decline in the annual fertility rate will persist, leading to smaller families going forward. The interesting thing about the current report is the fact that postponement has not been associated with lower lifetime births.