Why the Decline in Homeownership Is Bad for Americans

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

The house serves as a major savings mechanism as well as a source of shelter and security.

Somebody breezed into my office last week convinced that people are making a serious mistake by investing their money in a house. She pointed to the low long-run return on the Case-Shiller house price index and concluded that everyone would be better off if they invested their money in equities instead. This conclusion seems wrong-headed for so many reasons that it’s hard to know where to start.

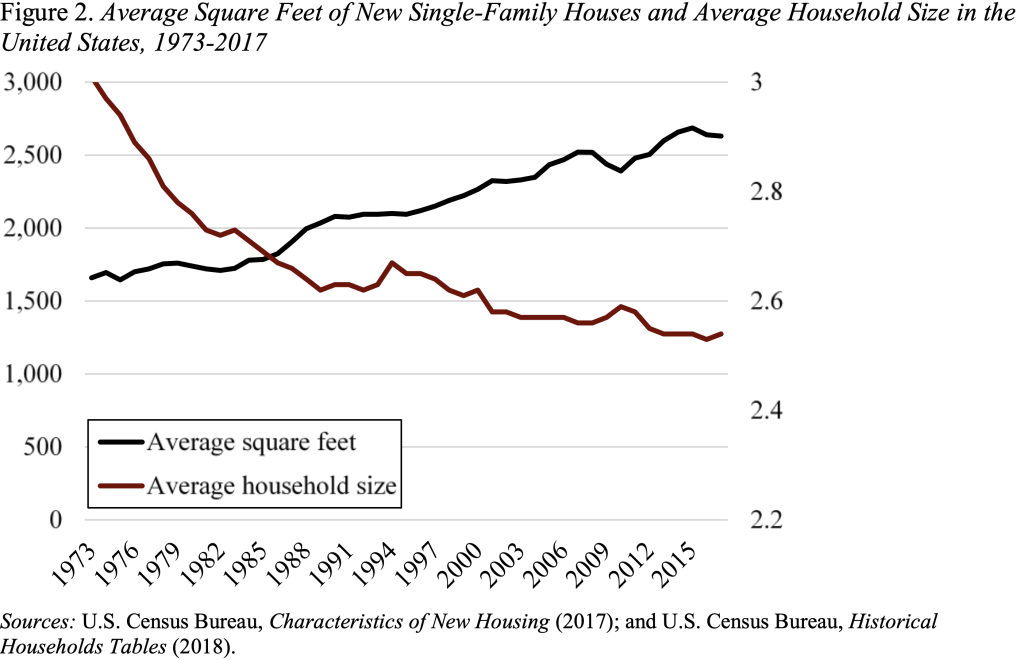

Perhaps, the return to housing might be a good place to begin. Yes, a leading house price index has averaged just 1 percent growth over the period 1968-2018, but the increase in the house price (P) is only one component of the return to housing. Imputed rent (I), essentially the payoff from not having to pay rent, is the other. To get the net return, it is necessary to subtract costs (C), which include property taxes, insurance, and maintenance. So, the expected return = P + I – C. To the 1-percent real increase in house prices add an assumed imputed rent of 8 percent and subtract costs of 3 percent for a net real return of 6 percent. This return is about the same as the long-run return on equities of 6 percent (see Figure 1).

Even more important, however, is that the house is a major vehicle through which people accumulate wealth for retirement. Saving is difficult, and most households, who have seen little growth in wages for decades, struggle to get by. They don’t have money left over to save. They accumulate wealth only through organized savings mechanisms, such as employer-sponsored retirement plans and repayment of mortgage loans. The idea that if people were not paying off their mortgage, they would be buying equities is preposterous. They would simply end up at retirement with less wealth.

And while people don’t currently tap their housing wealth in retirement, they value the house as insurance against the cost of high health care bills and the potential need for long-term care. Moreover, many households appear to have a strong desire to leave the house as a bequest, which allows middle-class families to transfer some wealth to their children.

Instead of talking people out of buying houses, we should be very concerned that Millennials, who were hit with student loans and a terrible job market as they got out of school, are not buying houses. They have essentially been forced to substitute student loan debt for mortgage debt.

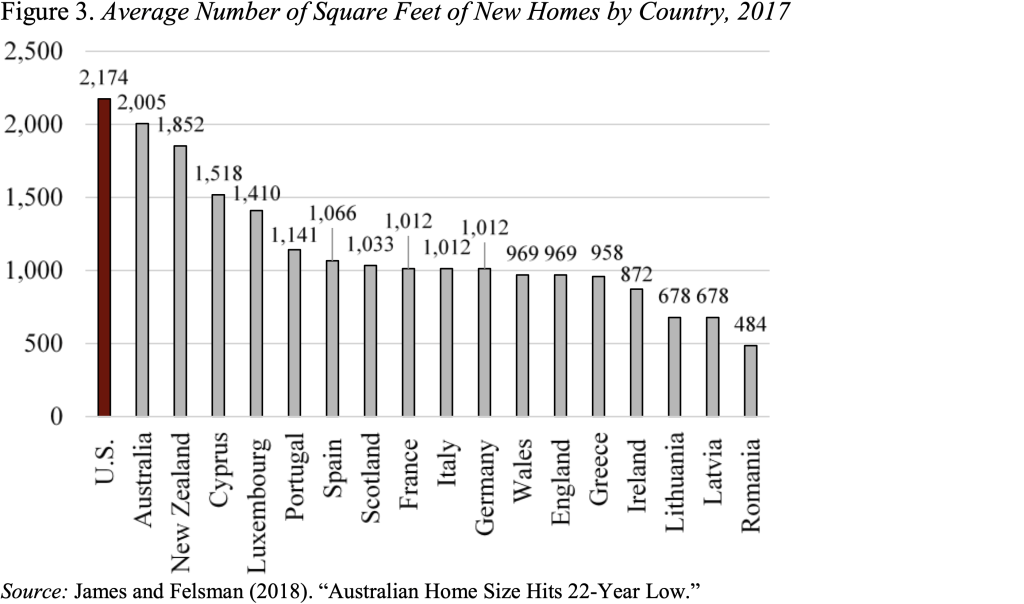

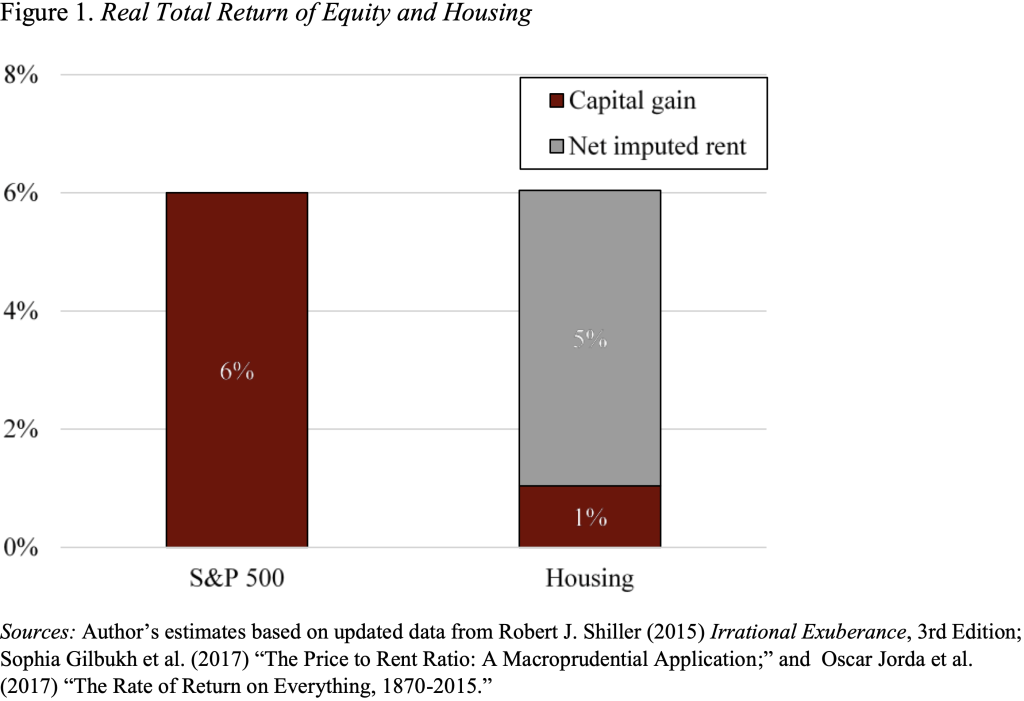

All that said, an argument could be made that Americans overinvest in housing. The average square footage of new single family housing has been rising sharply, even as the number of people in the average household has declined (see Figure 2). And houses in the United States are larger than in many other nations (see Figure 3). Persuading people to reduce the size of their house, however, is very different from telling them not to make this important investment.