401(k) Participation Rates Have Stalled

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

It’s time to make automatic provisions mandatory

When 401(k) plans began to spread rapidly in the 1980s, they were viewed mainly as supplements to employer-funded pension and profit-sharing plans. Since 401(k) participants were presumed to have their basic retirement income needs covered by an employer-funded plan and Social Security, they were given substantial discretion over 401(k) choices, including whether to participate, how much to contribute, how to invest, and when and in what form to withdraw the funds. Even though 401(k)s are now the primary plan for most workers, they still operate under the old rules. Thus, workers continue to have almost complete discretion over 401(k) choices.

Low rates of participation in 401(k) plans have been a major issue from day one. In the early years, 30 or 40 percent did not join. Behavioral economists suggested that changing the procedure from opting in to automatic enrollment (with the right to opt out) could greatly improve participation rates. Their studies showed that this simple change in the default could increase participation by about 40 percentage points (Madrian and Shea 2001). Even after three or four years, the vast majority of those automatically enrolled were still participating (Choi et al. 2001).

In an effort to make 401(k) plans work better, Congress enacted the Pension Protection Act of 2006, which contained provisions built on the work of the behavioral economists. The legislation encouraged automatic enrollment by eliminating obstacles and establishing a safe harbor whereby employers that adopt automatic enrollment are deemed to have met the “top heavy” and discrimination rules. The legislation also fostered automatic increases in the default contribution rate, so that automatic enrollees would not be locked into low levels of contributions.

The problem is that the Pension Protection Act only encouraged, rather than mandated, the adoption of automatic provisions. As a result, less than 50 percent of plans have automatic enrollment, and in most cases this feature is applied only to new entrants – as opposed to the entire workforce – so its impact is limited. Moreover, only about a third of those with automatic enrollment have automatic escalation in the default deferral rate.

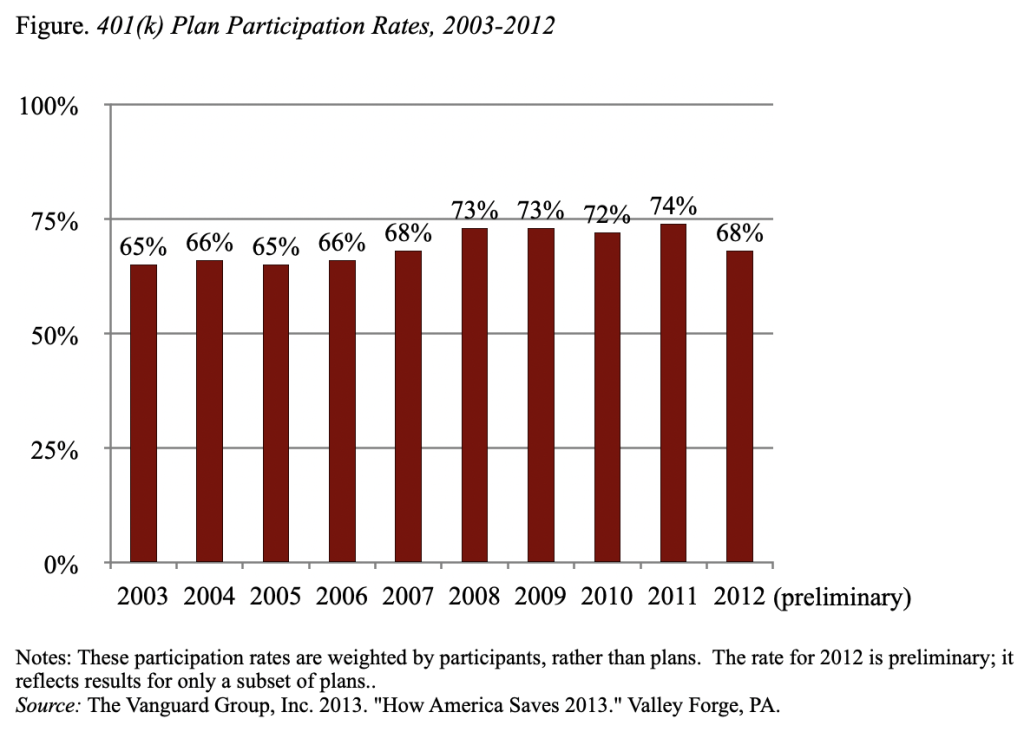

The limitation of the current law is evident in a recent update from Vanguard – How America Saves 2013. The participation rate for all employees in Vanguard plans rose about five percentage points after the Pension Protection Act provisions went into effect at the end of 2007 (see Figure). Since then, however, participation rates have leveled off at around 73 percent. (The preliminary 2012 figure is likely to be revised up.)

To make 401(k)s work better, the law should be changed to require all 401(k) plans to adopt annual auto-enrollment for their entire workforce. Auto-enrollment deferral rates should be set at a meaningful level and be accompanied by annual auto-escalation in the deferral rate. In other words, the time has come to make the automatic provisions mandatory components of 401(k) plans.