Fixing Social Security Requires Revenue Increases or Benefit Cuts

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Increasing the Full Retirement Age is not a third option; it’s an across-the-board benefit cut.

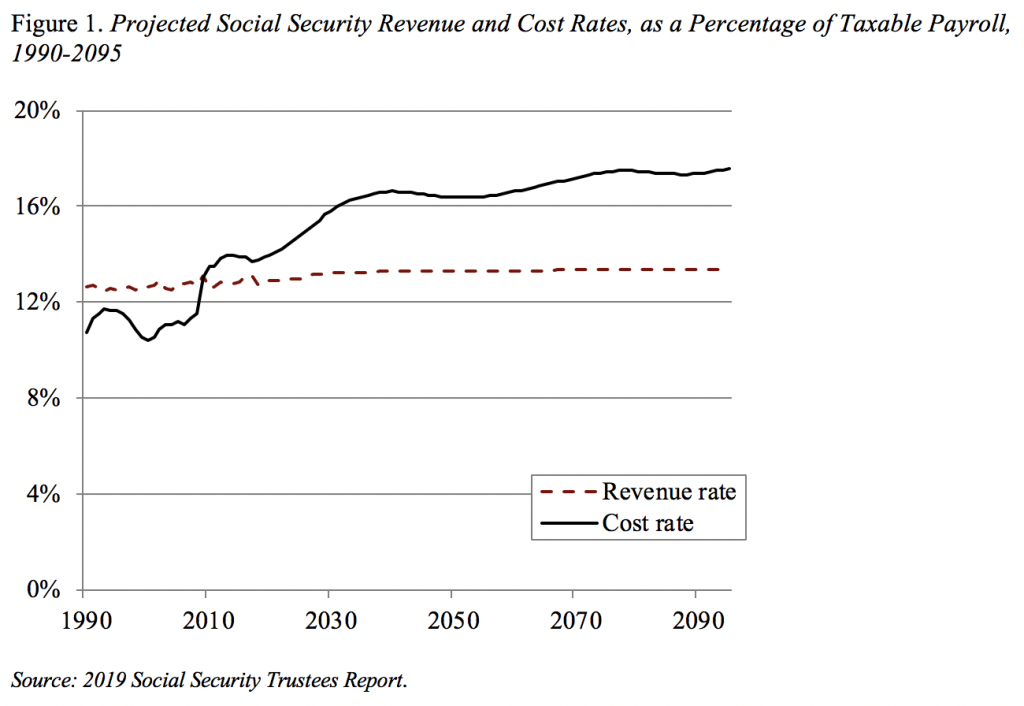

In this campaign season, fixing Social Security is once again emerging as a major topic. As Figure 1 shows, the cost of the program as a percentage of payrolls is higher than revenues. In the short term, the gap can be filled by drawing down the trust fund that was built up after the 1983 legislation. Once the trust fund is exhausted, revenues will be sufficient to cover only about 75 to 80 percent of scheduled benefits.

The key question is whether we want to increase revenues – that is, bring the revenue line up to the cost line – or cut benefits – that is, bring the cost line down to the revenue line – or some combination of the two. It’s a straightforward issue. I lean towards raising additional revenues and not reducing benefits. But my preferences are not the subject of this blog. Rather, my goal is to squelch the notion of a “third option” – increasing the Full Retirement Age (FRA). There is no third option; increasing the FRA is a benefit cut and a bad one at that.

Social Security’s FRA under current law is in the process of moving from 65 to 67. To keep lifetime benefits for the average worker roughly constant, benefits claimed earlier than the FRA are actuarially reduced and benefits claimed later are actuarially increased.

Those advocating increases in the FRA are responding to the fact that, generally, we are living longer and can work longer. But increasing the FRA to, say, 70 (after it reaches 67) would be equivalent to about a 20-percent reduction in benefits, which would be particularly hard on the lower paid because they tend to retire early.

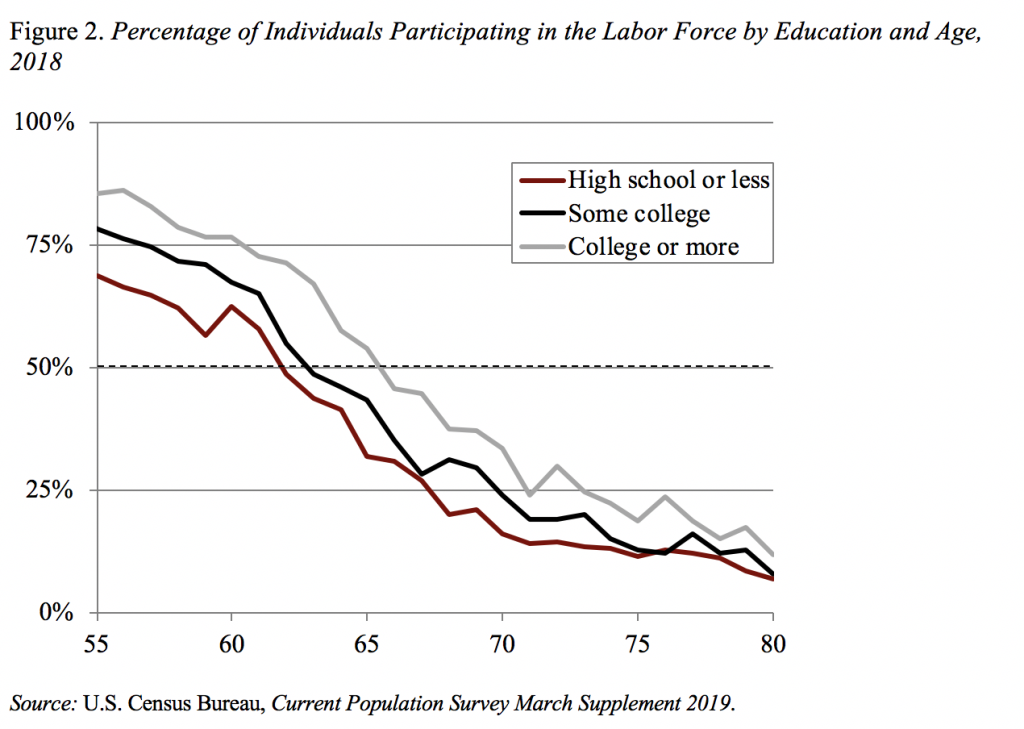

This impact can be seen in Figure 2, which shows the average labor force participation rate for those with a high school degree or less (roughly the bottom third of the education distribution), those with some college but no four-year degree (the middle third), and those with a four-year degree (the top third). Although education is not a perfect proxy for lifetime earnings, the two are highly correlated. If the average retirement age is defined as the age at which half the group is out of the labor force, then the average retirement age is about 62 for the low earners, 63 for the middle earners, and 66 for the high earners.

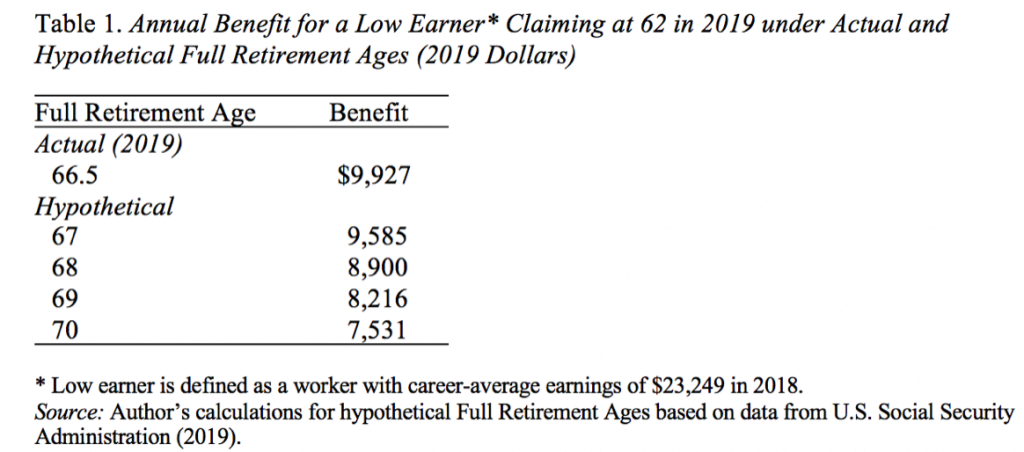

Table 1 shows what happens to the dollar benefit of the low earner retiring at 62 as the FRA increases from 66.5 (the actual FRA in 2019) to 70. For each full year the FRA increases, the benefit declines by about 7 percent on average.

Cutting benefits for this vulnerable low-earning population is bad policy. If we want to cut benefits, it makes much more sense to directly change the benefit formula. Such an approach allows for larger cuts for the higher-paid than for those at the bottom of the earnings distribution.

More fundamentally, let’s start being candid about changes to the Social Security program. They involve either a revenue increase or a benefit cut. There is no “third way.”