ESG – or Socially Responsible – Funds May Soothe Your Conscience but Could Weaken Your Portfolio

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

And despite the hype, new study concludes it hurts returns.

I have always been an opponent of social investing – that is, investing with the aim of making a political statement – in the public pension environment. It’s an easy case to make for a number of reasons. First, while such efforts often have powerful emotional appeal, they have no impact on the targeted companies, especially since the Vice Fund stands ready to buy stocks diverted from standard portfolios. Second, public plans are particularly ill equipped to integrate another criterion in their investment decision-making. Third, the people advocating for divestiture – today’s politicians – are not the ones who will bear the burden of lower returns – tomorrow’s retires and taxpayers.

Until recently social investing wasn’t a real issue for private plans because guidance from the Department of Labor clearly stated that plan trustees or other investing fiduciaries may not accept higher risk or lower returns in order to promote social, environmental, or other public policy causes.

In 2015, however, the agency clarified that fiduciaries may incorporate environmental, social, and governance (ESG) factors into the investment decision. The argument was that these factors may have a direct impact on the economic value of a plan’s investment, and, as such, should be integrated into risk and return calculations, alongside financial indicators. In 2018, the agency clarified that ESG factors should only be considered as a tie-breaker or if they represent material risks or opportunities.

Since 2015, ESG investing has become very popular. At one level, ESG investing makes sense. Consumers may value products that are produced in an ESG compliant manner, and workers may prefer companies that operate consistent with ESG principles. If so, then good ESG behavior will also produce higher returns. And indeed, stories abound about the financial success of ESG investing.

A recent study from the Pacific Research Institute, however, moves from the anecdotal to the systematic and concludes that ESG investing produces poor outcomes. (I don’t know the author or the institute, but the study came from a reputable guy and the methodology seems sensible.)

The study looks at 30 ESG funds that have either existed for more than 10 years or have out-performed the S&P over some short-term time frame. These funds tend to fall into three categories: 1) “broad-based index” funds that exclude one or more of the following industries: gambling, alcohol, tobacco, fire arms or fossil fuel; 2) “waste and clean tech” funds that invest in alternative technology and clean waste management – that is, they pursue the environmental component of ESG; and 3) “social goals” funds that use explicit social goals, such as strong women leadership, to select companies.

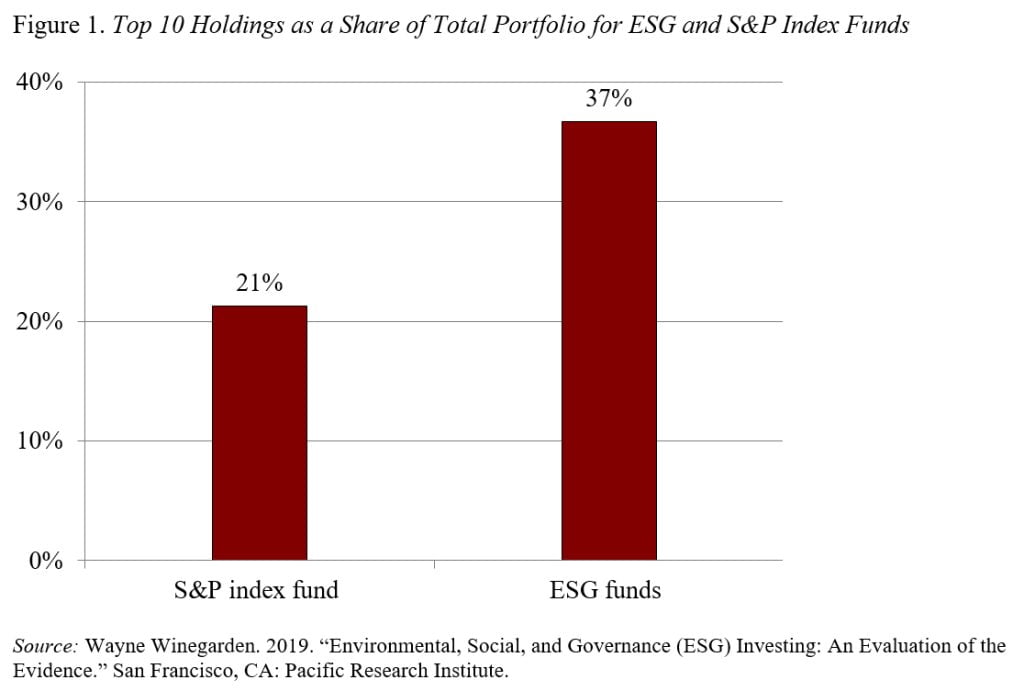

The results show that all three types of ESG funds do not perform as well as an S&P index fund. First, ESG funds are more concentrated in a few companies than an S&P index fund (see Figure 1). The higher is the share of the top 10 investments, the smaller the benefits of diversification and the greater the risk.

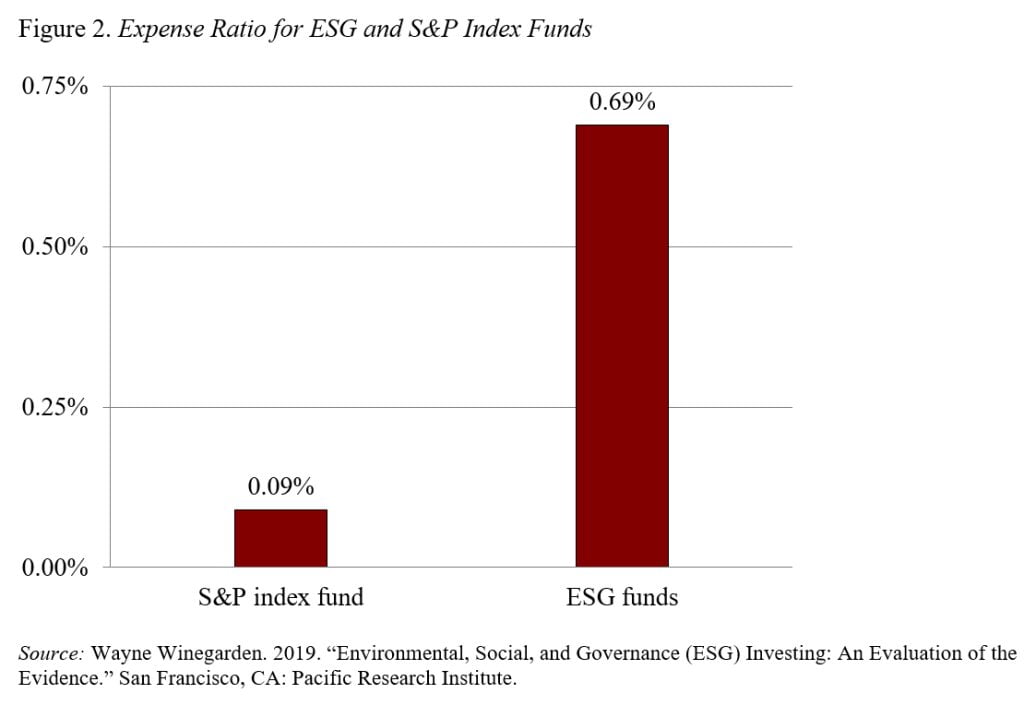

Second, ESG funds have higher expense rations than an S&P index fund. A 60-basis- point higher expense will reduce accumulations by 15 percent over a 25-year span.

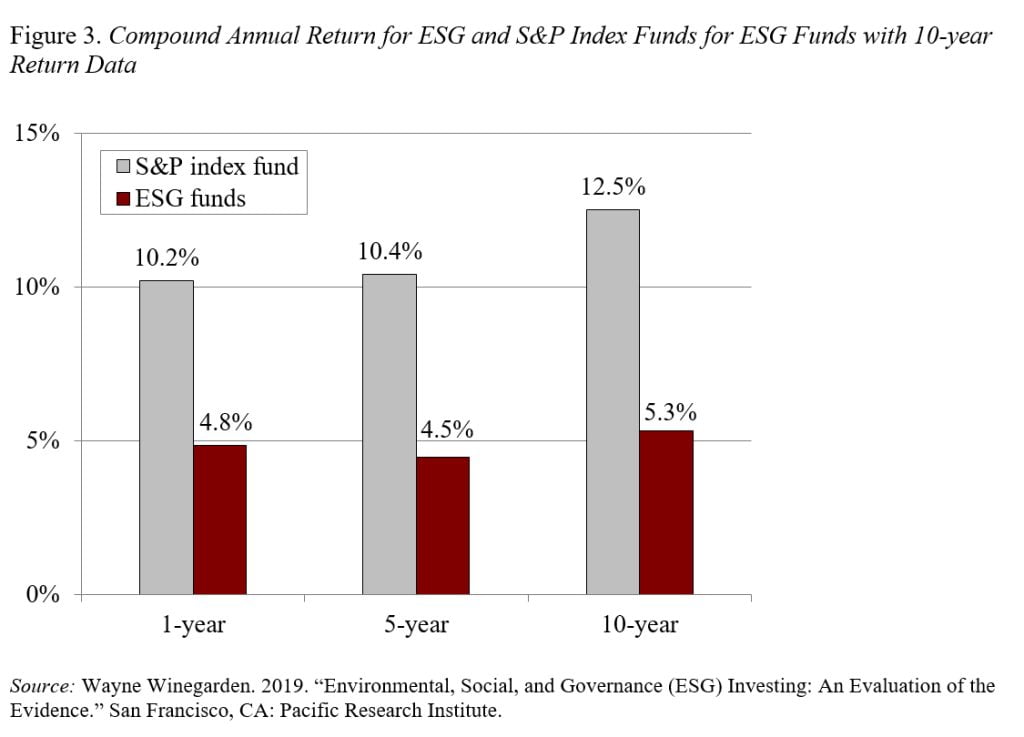

Third, focusing on a subset of the ESG funds (18 of the 30) that have been in existence for ten years, the results show that the ESG funds have been unable to match the S&P index fund in 1-year, 5-year or 10-year performance (see Figure 3).

With more risk, higher fees, and lower returns, investors should think seriously before getting into the ESG game.