Connecticut and New Jersey – Similar Problems, Different Solutions

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Attitudes towards pension commitments differ dramatically between similarly situated states.

Listening to the rhetoric coming out of New Jersey and Illinois, one might conclude that the whole country wants to renege on promised pension benefits. In New Jersey, the Governor’s Commission concluded that the state could not pay its promised benefits and the only way forward is to close down the state’s defined benefit plans and cut back on promised retiree health insurance. In Illinois, the legislature had passed a reform plan that would have made less drastic changes, but still provided less than employees had been promised; this plan was subsequently overturned by the Illinois Supreme Court.

In fact, most states have well-run pension plans, are recovering from the financial crisis, and fully intend to pay the benefits they have promised to their public sector workers. Granted, many have reduced benefits for new employees and have lowered their cost-of-living adjustments, but most states are committed to providing the full amount of core benefits. In comparison, New Jersey and Illinois are outliers.

One could argue that these outlier states have painted themselves into such a corner that the only option is reneging. But here a comparison between New Jersey and another poorly funded state – Connecticut – is quite illuminating, because the two states face similar fiscal landscapes yet offer very different responses.

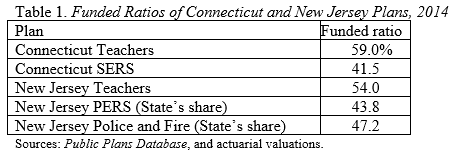

Both New Jersey and Connecticut have significantly underfunded plans (see Table 1).

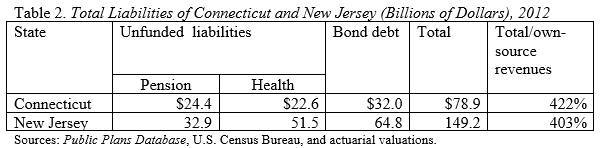

But a state’s fiscal picture depends on more than pension commitments to its workers. States have also made commitments to provide health insurance to their retirees and interest payments to their bond holders. Table 2 shows the total amount of pension, retiree health, and bond debt outstanding. New Jersey appears to have roughly twice as much overall debt as Connecticut, but it is a much larger state. Relating the total debt for each state to its own-source revenues shows that the two have comparable levels of indebtedness.

Finally, states could react differently to their burdens depending on the current level of taxation. That is, a low-tax state would have much more room to raise revenues to pay off its debts than a high-tax state. Interestingly, both Connecticut and New Jersey are high-tax states, ranking 2nd and 8th respectively, according to Census data for 2012.

In short, New Jersey and Connecticut look almost identical in financial terms, but have responded very differently to unfunded pension plans. New Jersey’s Governor Christie has declared war on public employees, refusing to make promised pension contributions and creating a commission as cover for reneging on the state’s pension and health care promises. Connecticut’s Governor Malloy, in contrast, repeatedly emphasizes his commitment to improving the funding of Connecticut’s public pensions. Since the difference in response is not driven by finances, it must reflect attitudes towards public employees – and importantly – towards their unions.