Social Security’s COLA 0.3 Percent for 2017

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

This annual adjustment always raises the question of what’s the right price index.

The Social Security Administration recently announced that in 2017 beneficiaries will receive a cost-of-living adjustment of 0.3 percent, after having received no increase for inflation in 2016. Automatic indexing is generally viewed as a positive feature of social security systems, both in the United States and abroad. Without such automatic adjustments, the government would have to make frequent changes to benefits to prevent retirees’ standard of living from eroding as they age.

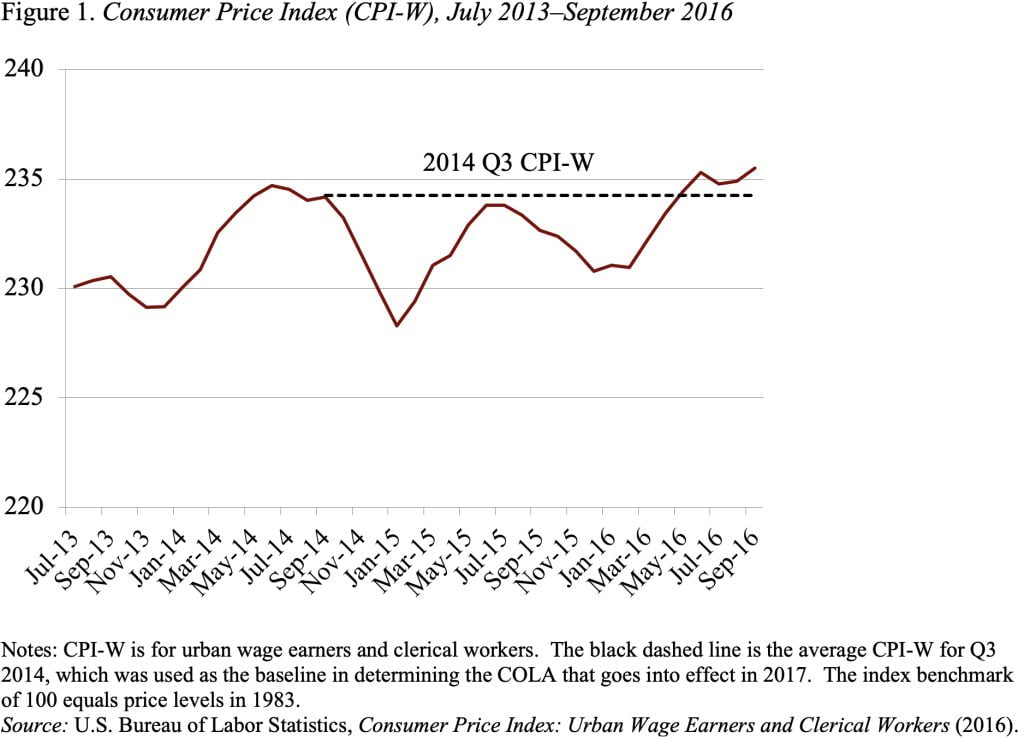

The Social Security COLA is based on the change in the Consumer Price Index for Urban Wage Earners and Clerical Workers (CPI-W) over the most recent year with a COLA increase (2014). Since the COLA first affects benefits paid after January 1, Social Security needs to have figures available before the end of the year. As a result, the adjustment for January 1, 2017 is based on the increase in the CPI for the third quarter of 2016 over the third quarter of 2014. As shown in Figure 1, the reason for no COLA in 2016 is that the CPI-W dipped substantially from the 2014 third-quarter average of 234.2 and, although it turned around, remained below that benchmark in the third quarter of 2015. The reason for the 0.3 percent COLA in 2017 is that the third quarter of 2016 was 0.3 percent higher than the 2014 peak (235.1/234.2).

Whether the government is using the appropriate price index to adjust Social Security benefits is a controversial issue. Some critics contend that the adjustment is too small because the CPI-W does not reflect the spending patterns of the elderly and that, therefore, the government should use a special index just for the elderly. Other critics contend that the adjustment is too large because the CPI-W does not adequately reflect the ability of individuals to switch from high-priced goods to lower-priced substitutes and the government should use a chain-weighted index.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics does calculate an experimental price index for the elderly (persons 62 and older), which is known as the CPI-E. Over the period 2000-2014, the average annual increase for the CPI-E was 2.36 percent, compared to 2.23 percent for the CPI-W – a gap of 0.13 percent. The CPI-E rose faster, in part, because older people devote a larger share of their budgets to medical care, and the cost of this item rose faster than prices in general.

Other critics argue that a chained CPI would be more accurate since it reflects the extent to which people substitute one item for another in the face of a price increase. Between 2000 and 2014, the chained CPI has increased an average of 0.18 percentage points slower each year than the unchained version.

If benefits were currently adjusted by the appropriate index, introducing a chained index would probably improve accuracy. But the CPI-E suggests that the current index understates the inflation faced by the elderly. Thus, any adjustment to the nature of the COLA would need to consider both the projected 0.18 percent overstatement due to not accounting for the substitution effect and the projected 0.13 percent understatement due to not reflecting the spending patterns of the elderly. So the current index may not be far off the mark.