The U.S. Fertility Rate Is Falling. Is There Anything We Can Do?

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Policies tried by countries like Sweden might prevent the fertility rate from falling further.

The decline in the fertility rate is a significant development, not just in the U.S. but around the world. Some laud the trend as an example of women’s ability to control their destiny; others decry it as an economic catastrophe. Regardless of one’s views, at current levels of fertility, the world’s population is projected to peak in the 2060s and then start to decline, which may not be such a good thing.

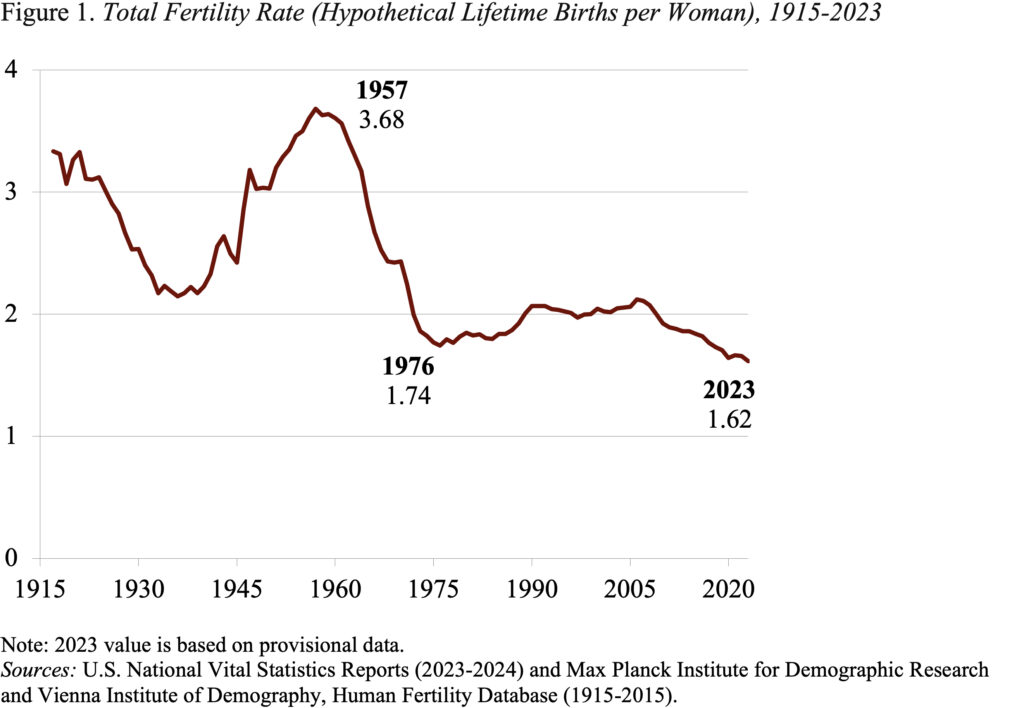

In the U.S., fertility rates have generally been falling since the end of the baby boom in the mid-1960s, and that decline accelerated after the Great Recession. Many observers thought that once the economy recovered, the fertility rate would rebound. Clearly, it has not (see Figure 1). To me, this is not a surprise. My colleague Angie Chen and I found in 2018 that the downward trend could be explained by underlying factors – particularly, the increase in women’s education and earnings – that were not likely to reverse. In 2023, the fertility rate was 1.62, an all-time low and way below that needed to maintain the current population.

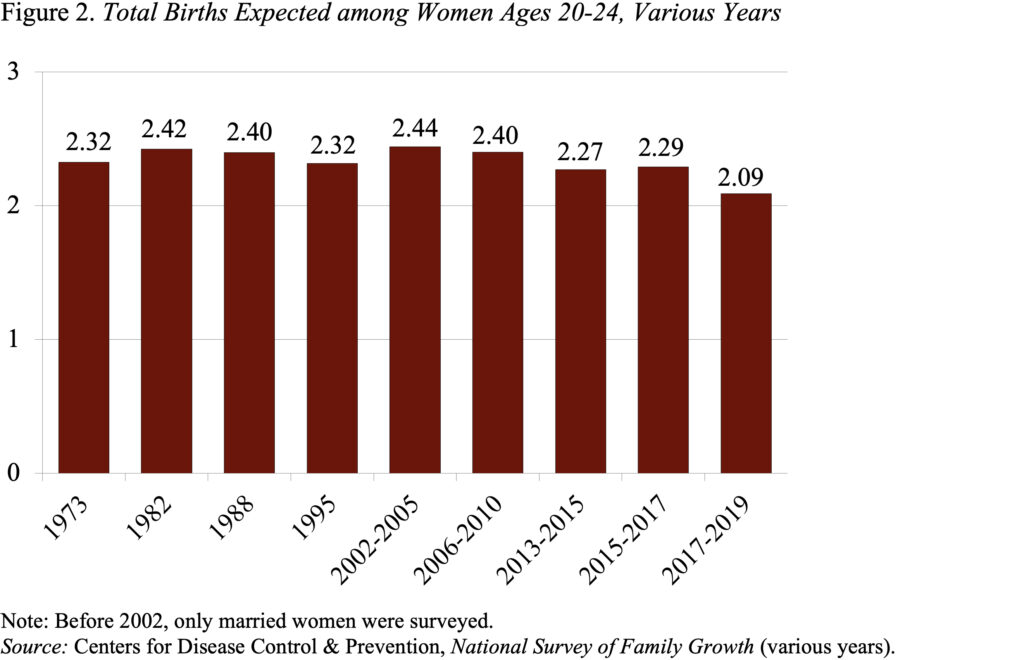

Interestingly, survey data suggest that women in their 20s still expect to have more than two children (see Figure 2), albeit fewer than in previous surveys. The big disconnect between expectations and births means that something is making it difficult to become a parent. Clearly people are getting married a lot later; in 2023, the median age of first marriage for women was 28 – about 6 years later than in the early 1980s. Prospective parents also may want to reach other milestones before having a child, such as paying off student debt or buying a house. That makes sense given the enormous cost of childcare.

All these problems seem very American, however, so I was interested in what was happening in other countries, where government policies are more benevolent. I was particularly interested in Sweden, where the government seems to have done everything possible to help new families.

- Parental Leave: 480 days per child, with each parent entitled to 240 days.

- Financial Support: For the first 390 days, compensation is based on a parent’s income up to a cap, and for the remaining 90 days, a fixed amount (approximately $17) per day

- Flexible Work Arrangements: Upon returning to work, parents may reduce their hours to 75 percent or more until the child turns eight.

- Child Sick Leave: Parents are entitled to up to 120 days of leave per child per year.

- Childcare and Preschool: Subsidized childcare and free preschool from ages one to six.

- Universal Healthcare: Maternal care and child healthcare services are free.

- Education: Free primary, secondary, and upper secondary education.

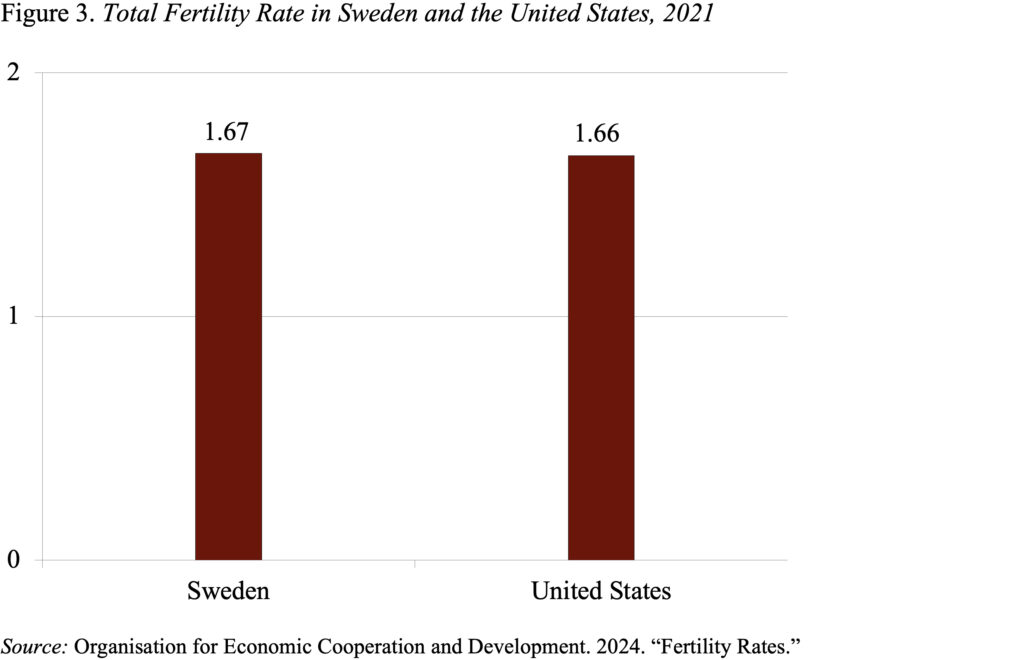

All these provisions sound lovely compared to the U.S.; parents bear almost no financial costs associated with having children, and the workplace appears very accommodating. So how do Swedish fertility rates compare with those in the U.S.? Data for 2021 show that they are identical (see Figure 3).

That identity doesn’t mean that Sweden has bought nothing with its generous parental policies. Since 2000 – when many of these policies were introduced – Sweden’s fertility rate increased from 1.55 to 1.67, while the rate in the U.S. declined from 2.06 to 1.66. Further, the labor force participation rate for women in Sweden is 88 percent compared to only 75 percent in the U.S.

The Swedish results do suggest that it is very, very difficult for the government to increase the fertility rate. That said, we could try to make it a little easier for women to both work and have children. Such efforts may prevent the fertility rate from falling further.