A Real Debate on Taxes

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

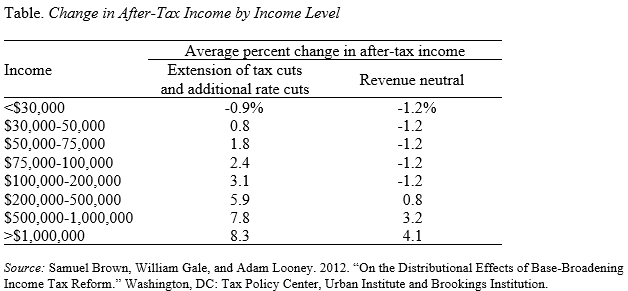

The Republican candidates have made it very clear that increased revenue should play no part in the effort to restore fiscal balance. As a result, all the balancing is accomplished through cuts to programs, including those that many retirees rely on such as Medicare. Moreover, a recent analysis of Governor Romney’s tax proposals by the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center concludes that his revenue neutral changes would provide large cuts to high-income households and raise taxes on middle and lower-income households.

As described on Romney’s website, his tax plan would extend the 2001-03 tax cuts, reduce individual income tax rates by 20 percent, eliminate taxation of investment income for most taxpayers, eliminate the estate tax, reduce the corporate income tax rate, and repeal the alternative minimum tax and the high-income taxes enacted in the 2010’s health-reform legislation. These changes would reduce revenues by about $450 billion in 2015. Governor Romney and his advisors say that the ultimate plan would include proposals to broaden the base by eliminating tax expenditures so that his overall tax proposals would be revenue neutral.

Paul Ryan’s plan is quite similar. He calls for collapsing the income tax rates into brackets, 10 and 25 percent, which represents an even larger cut in the highest marginal rate than the Romney plan. He also proposes making up the lost revenue by eliminating unspecified tax expenditures.

Because the tax expenditures to be eliminated are unspecified, the analysts need to make some assumptions. First, consistent with statements by Romney and supporters, they assume provisions to encourage saving, such as preferential rates on capital gains, tax preferences for retirement, health and educational savings accounts, exemption of interest on state and local bonds, the exclusion of capital gains in home sales, and the Saver’s Credit, would not be eliminated. Second, they eliminate tax expenditures by “starting at the top.” That is, they first eliminate tax expenditures for the highest income group (deductions for charitable contributions, mortgage interest, state and local taxes, and exclusions from income of health insurance and other fringe benefits) and then work their way down the income distribution until they have recouped all the revenue loss so that the tax cuts are revenue neutral.

The key finding is that (once tax expenditures to encourage saving are off the table) the total value of the tax breaks that these taxpayers are now enjoying (i.e., the amount that could potentially be eliminated under the proposed tax changes) is smaller than their gain from the rate cuts. As a result, the arithmetic requires that part of the burden for the high-income rate cuts shift onto middle- and low-income taxpayers. That is, once savings incentives are off the table, it is not possible to design a revenue-neutral plan that does not reduce tax burdens paid by high-income taxpayers, even if the reductions are implemented in the most progressive way possible.

As shown in the table, the after-tax income of those earning more than $1,000,000 would increase by 4 percent in this revenue neutral exercise, while that of those with $75,000- $100,000 would decline by 1.2 percent.

The fact that the existing tax system becomes more regressive under Governor Romney’s tax proposals is interesting, but somewhat small potatoes compared to the fact that he and Paul Ryan envision no role for increased revenues in closing the fiscal gap. As a result, the entire burden falls on program cuts, which fundamentally affects the lives of low- and middle-income families. Now, that is something to have a debate about!