Achieving 75-Year Balance Not the End of the Story

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Due to a growing ratio of retirees to workers, a lasting fix will require additional changes.

At this point, any plan to restore balance to Social Security would be so welcome that I hesitate to mention possible pitfalls. But a problem does arise from focusing on the 75-year deficit. Seventy five years has been the historical planning period because it approximates the number of years that the average adult spends in the system. In my view, it is a perfectly reasonable horizon. Once we reach a steady state in which the ratio of retirees to workers stabilizes and costs remain relatively constant as a percent of payroll, any solution that solves the problem for 75 years will more or less solve the problem permanently.

But we are in a period of transition. The ratio of retirees to workers is rising from 35 in 2012 to 52 in 2086, so the cost rate is projected to rise from 13.8 in 2012 to 17.8 in 2086. Any package that restores balance only for the next 75 years will show a deficit in the following year. This deficit arises because as the projection period moves from 2012-2086 to 2013-2087, it picks up a year with a large negative balance. And that negative balance causes a deficit over the new 75-period.

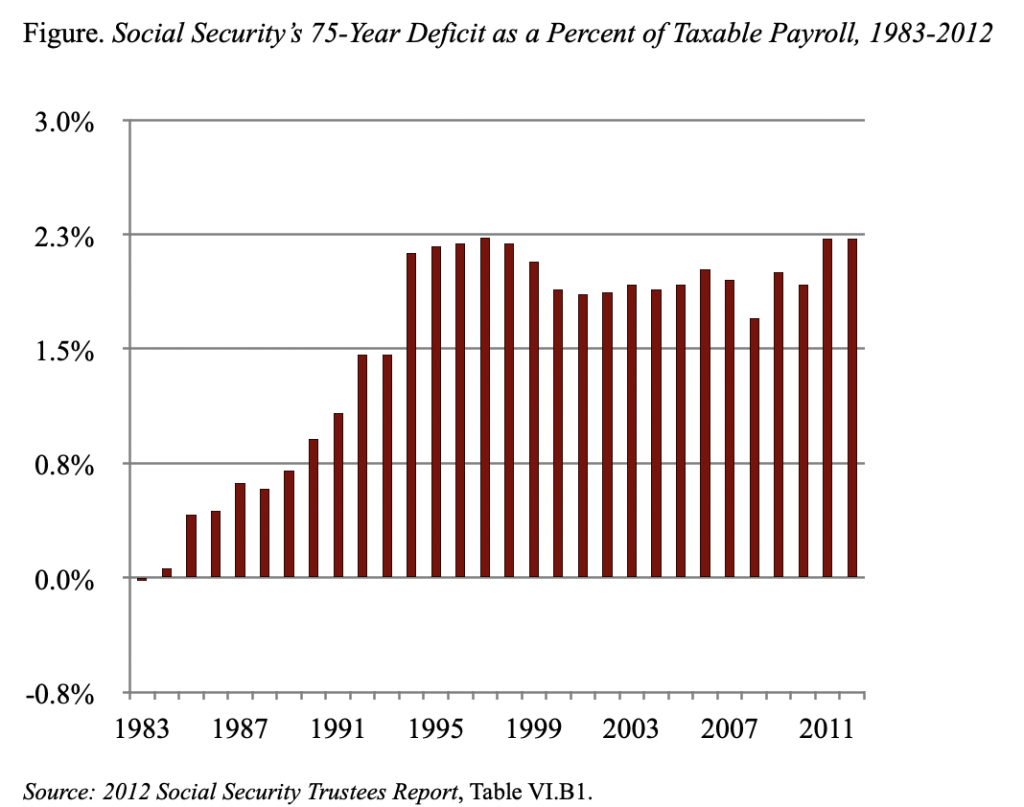

This pattern of immediate deficits just after a 75-year solution happened after the financial fix in 1983, as a result of recommendations from the “Greenspan Commission.” As the Figure shows, a small surplus became a small deficit and then larger deficits over time.

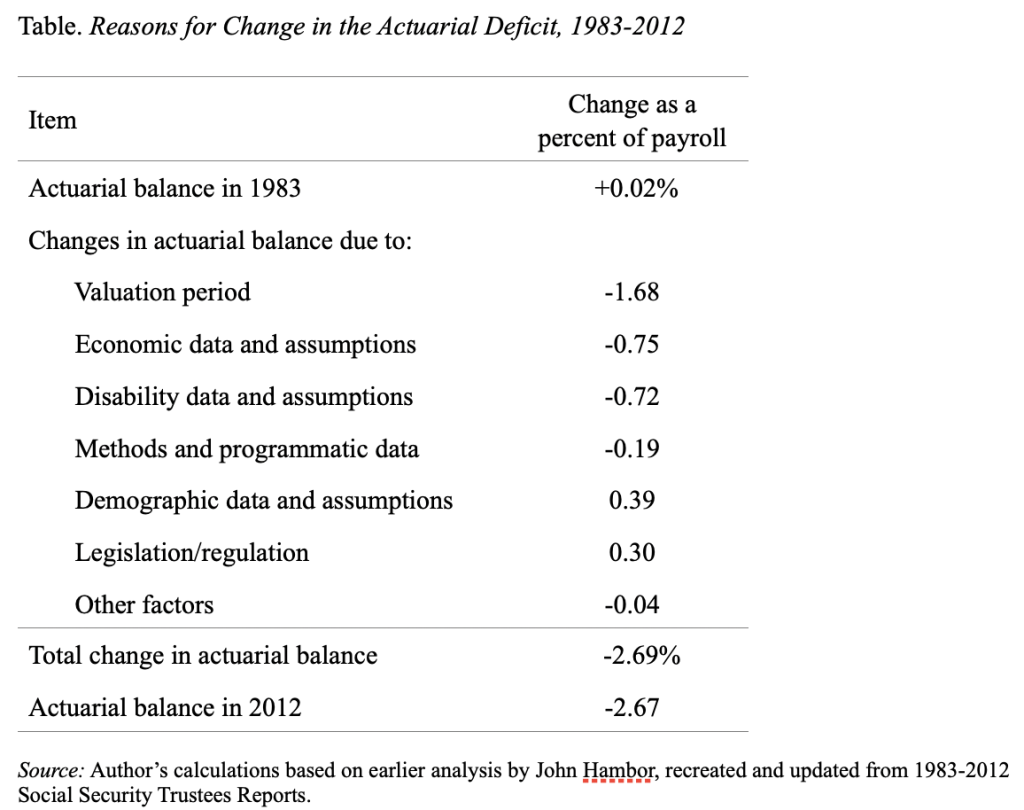

Several factors explain how we moved from a small surplus in 1983 to a deficit of 2.67 percent of payroll in 2012. Leading the list by far, however, is the shifting of the valuation period (see Table).

Policymakers generally recognize the negative effect of picking up deficit years as the valuation period moves forward and many advocate a solution that involves “sustainable solvency,” in which the ratio of annual trust fund assets to outlays is either stable or rising in the 76th year. The problem is that achieving this laudable goal requires larger tax increases or benefit cuts than a 75-year fix.

The issue seems to be one of packaging. People need to know that eliminating the 75-year shortfall should be viewed as the first step toward long-run solvency. A lasting fix for Social Security would require additional changes. And the more that those changes can either be put in the law or at least spelled out in some detail, the more confidence people will have in the financial sustainability of the program. And confidence in Social Security is crucial given that it is the backbone of our retirement system.