Alternative Investments Have Not Helped Public Pension Plan Returns, Study Shows

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

And in recent years, they have actually hurt; although they may have dampened volatility.

In fiscal year 2022, state and local pension plans have seen the decline in the stock market erase much of the gains from 2021. And, recent media reports by Pensions and Investments, The Wall Street Journal, and others have suggested that alternative investments are one reason why reported returns don’t look even worse.

But have alternatives generally helped? Not according to a recent study by my colleague JP Aubry. He found that plans’ increasing reliance on alternative investments has not improved long-term returns since 2001, and over the past decade has actually hurt — although it may have dampened volatility.

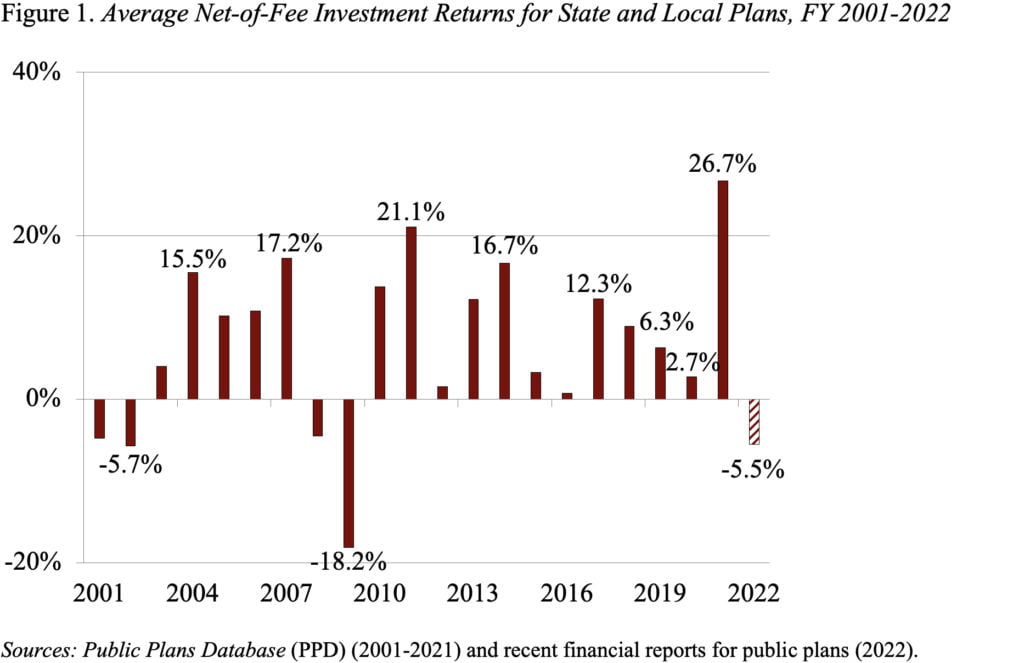

Let’s start with an update of the performance of state and local pension plans (see Figure 1). After a banner year in FY2021, financial markets collapsed and public pensions saw an average negative return of 5.5 percent in FY 2022. Given the whipsaw nature of returns, it’s impossible to say on a year-to-year basis whether holding more alternatives helps or hurts. Such an assessment requires a longer-term perspective.

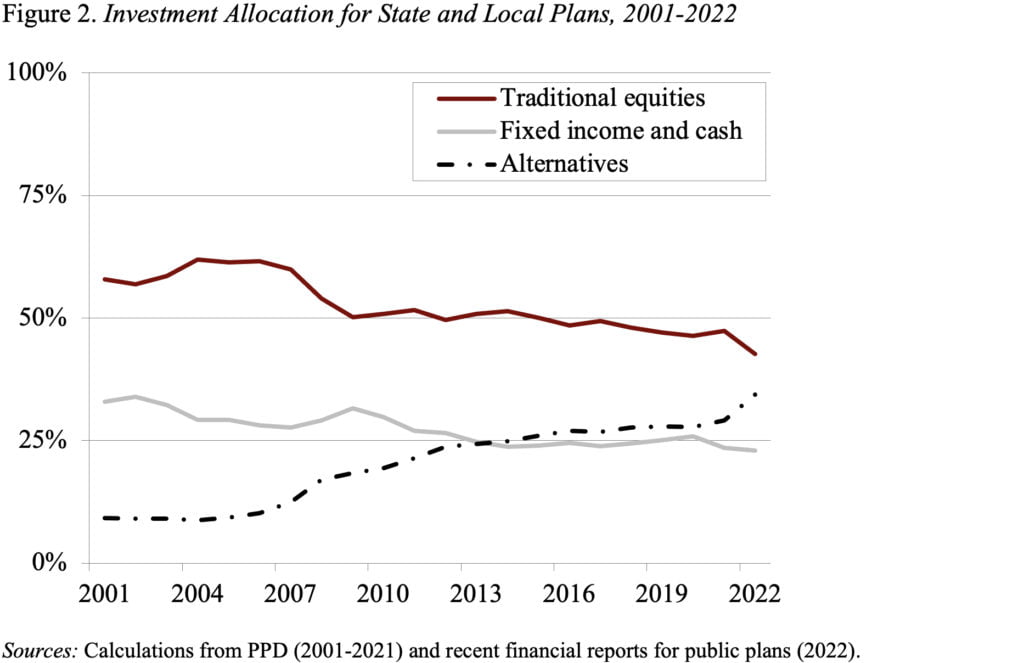

For public pension funds, the aggregate allocation to alternatives first began to rise in 2005 (see Figure 2). Almost by definition, the precipitous drop in equity values compared to other assets in 2008 and 2009 led to further increases in the shares held in all other asset classes. As the stock market recovered, however, the allocation to traditional equity remained depressed, suggesting that plans were making deliberate shifts towards alternative investments. Overall, state and local plans have increased their holdings of alternatives from 9 percent in 2001 to 34 percent in 2022.

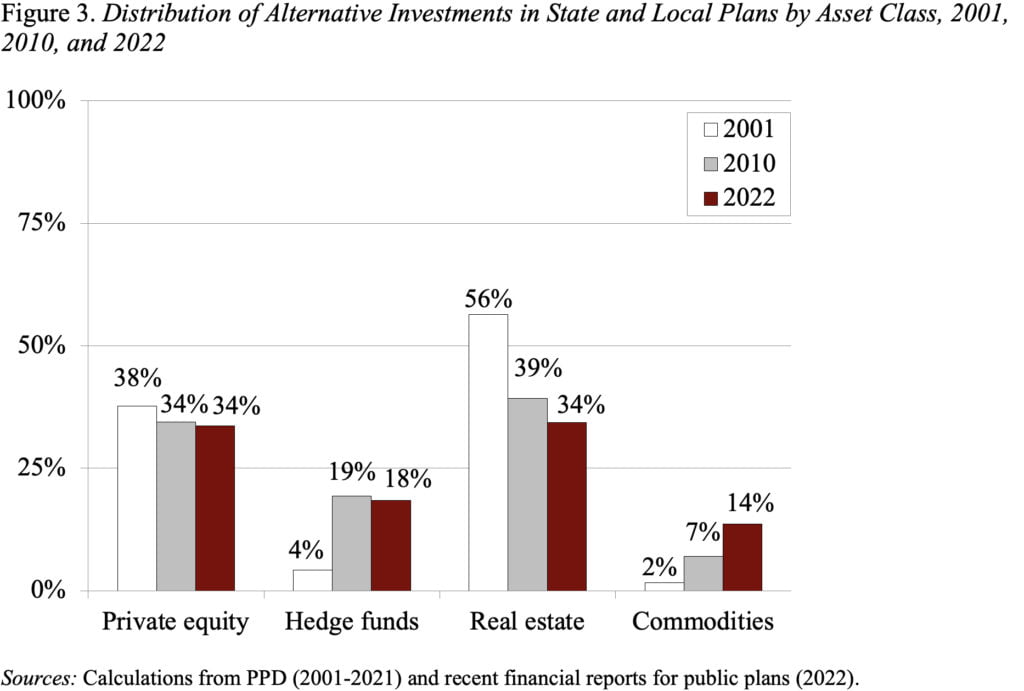

Not only have alternatives become a much larger share of public plans’ portfolios, but their composition has also changed. As shown in Figure 3, between 2001 and 2022, the portion of alternative investments allocated to real estate has dropped sharply, while allocations to hedge funds and commodities have grown.

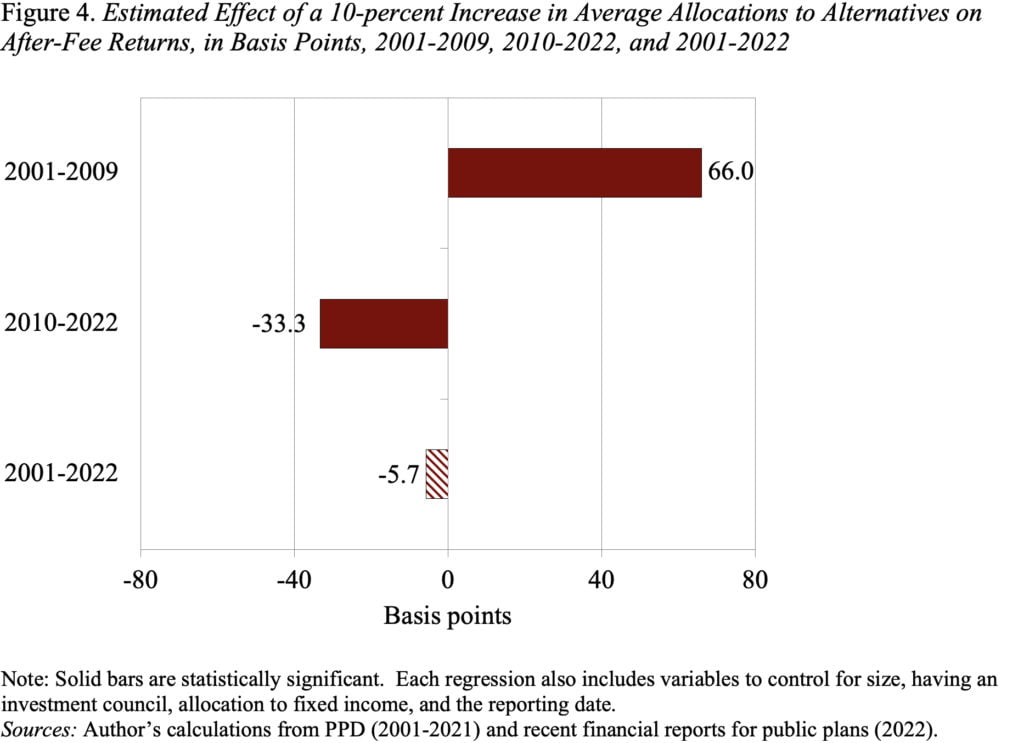

JP estimates the relationship between a pension fund’s allocation to alternatives and its overall portfolio performance for three periods: 2001 to 2009 (before and during the global financial crisis), 2010 to 2022 (post-crisis), and 2001 to 2022 (pre- and post-crisis). The equation controls for the plan’s allocation to fixed income and cash, plan size, the presence of a separate investment council, and type of fiscal year.

The results show that, relative to traditional equities, holding 10 percent more of the plan’s portfolio in alternatives is associated with a 66-basis-point increase in the portfolio return from 2001 to 2009 and a 33-basis-point decrease in the return from 2010-2022 (see Figure 4). Given the opposing results before and after the global financial crisis, it is perhaps unsurprising that the allocation to alternatives had no statistically significant impact on returns when looking over the whole period from 2001-2022. The study goes on to look at the contribution by type of alternative: over the whole period, only hedge funds had a statistically significant impact, and it was negative.

Pension funds care about more than investment returns over the long run, so the analysis also looked at the relationship between holdings in alternatives and volatility (i.e., the standard deviation) in reported annual pension fund returns. The results show that plans with greater overall allocations to alternatives have experienced lower volatility in their annual returns since 2010 and over the whole period since 2001. But it is hard to determine how much of this impact is real rather than due to the way alternatives are reported.

In terms of returns, however, alternatives have not helped over the period 2001-2022 and, in fact, have hurt in recent years.