How Big Is the Secure 2.0 Act? And Who Gets the Money?

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

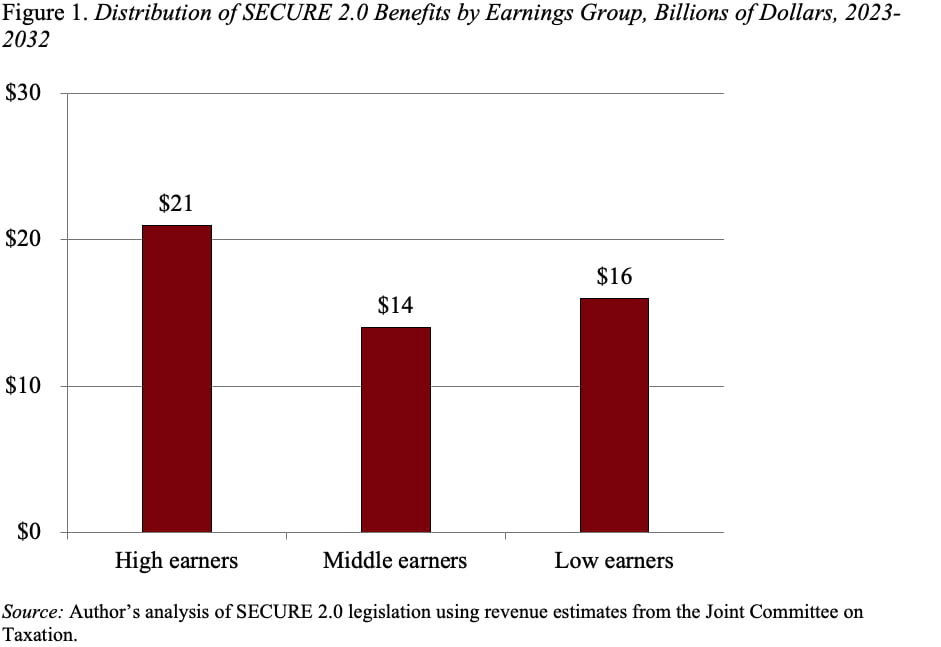

Most benefits still go to top third, but expansion of Saver’s Credit improves the optics.

A reporter asked how big the new retirement law (Secure 2.0) was. Despite having the estimates from the Joint Committee on Taxation in front of me, I had to give a convoluted response. If we ignore the proposal to enable employers to establish emergency savings accounts, the answer is straightforward. The provisions cost about $51 billion.

This total is “paid for” primarily by three “revenue raisers.” 1) Catch-up contributions going forward must be made on a Roth rather a traditional basis ($17 billion). 2) Employer matching or nonelective contributions can be designated as Roth rather than traditional contributions ($14 billion). 3) Employers can offer emergency accounts within defined contribution plans funded with post-tax Roth contributions rather than traditional pre-tax contributions ($12 billion).

What outrageous budget gimmickry! The shift from traditional to Roth contributions increases revenues over the next 10 years – the budget window for evaluating the impact of SECURE 2.0 – but it reduces revenues by a comparable amount thereafter. The increase occurs in the short term because money going to Roths is taxed up front, while taxation of money contributed to traditional plans does not occur until retirement. In other words, in the long run, SECURE 2.0 is not really paid for. It will add $51 billion to the deficit.

[By the way, even though I don’t like counting the introduction of emergency savings accounts as a revenue raiser, I like the idea of these accounts. They give individuals easy access to funds when things go wrong; they may encourage participation in retirement plans; and, by distinguishing saving for emergencies from retirement saving, may end up protecting retirement saving. Under the legislation, employers that opt for emergency savings accounts must automatically enroll participants at a rate of 3 percent and contributions are capped at $2,500 (indexed for inflation). Participants can take at least one withdrawal per month.

The fact that SECURE 2.0 adds $51 billion to the deficit means that people will receive real benefits from this legislation either by paying less in lifetime taxes or receiving money in the form of a government match. Where will these benefits go? I read through the 82 provisions and allocated them to separate bins for low, middle, and high earners. According to my estimates, $21 billion goes to high earners, $14 billion to middle earners, and $16 billion to low earners (see Figure 1).

It’s important to point out how key to making this deal even remotely palatable is the expansion of the Savers Credit, which accounts for $9 billion of the $16 billion going to the bottom third of earners. The legislation provides a uniform credit rate of 50 percent and makes the credit refundable in the form of a government match on contributions to a retirement plan for eligible participants. Without the expansion of the Saver’s Credit, the legislation would have been shameful.