Caregiving Disrupts Work, Finances

What do groceries, GPS trackers, and prescription drug copayments have in common?

They are some of the myriad items caregivers may end up paying for to help out an ailing parent or other family member. And these are just the incidentals.

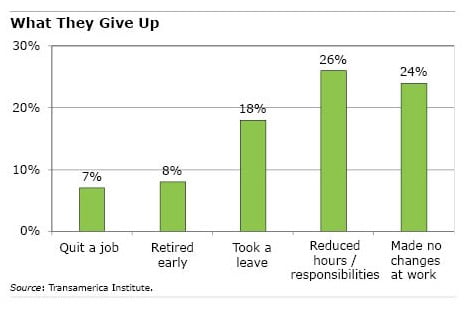

Three out of four caregivers have made changes to their jobs as a result of their caregiving responsibilities, whether going to flex time, working part-time, quitting altogether, or retiring early, according to a Transamerica Institute survey. To ease the financial toll, some caregivers dip into retirement savings or stop their 401(k) contributions. Not surprisingly, caregiving places the most strain on low-income families.

Three out of four caregivers have made changes to their jobs as a result of their caregiving responsibilities, whether going to flex time, working part-time, quitting altogether, or retiring early, according to a Transamerica Institute survey. To ease the financial toll, some caregivers dip into retirement savings or stop their 401(k) contributions. Not surprisingly, caregiving places the most strain on low-income families.

People choose to be caregivers because they feel it’s critically important to help a loved one, said Catherine Collinson, chief executive of the Transamerica Institute.

But, “There’s a cost associated with that and often people don’t think about it,” she said. “Caregiving is not only a huge commitment of time. It can also be a financial risk to the caregiver.”

The big message from Collinson and the other speakers at an MIT symposium last month was: employers and politicians need to acknowledge caregivers’ challenges and start finding effective ways to address them.

Liz O’Donnell was the poster child for disrupted work. As her family’s sole breadwinner, she cobbled together vacation days to care for her mother and father after they were diagnosed with terminal illnesses – ovarian cancer and Alzheimer’s disease – on the same day, July 1, 2014.

Her high-level job gave her the flexibility to work outside the office. But work suffered as she ran from place to place dealing with one urgent medical issue after another. She made business calls from the garden at a hospice, worked while she was at the hospital, and learned to tilt the camera for video conferences so coworkers wouldn’t know she was in her car.

“I felt so alone that summer,” said O’Donnell, who wrote a book about her experience. “We’ve got to do better, and I know we can do better.”

Caregiving is isolating in part because it is very time-consuming. Transamerica found that half of all caregivers devote, at minimum, 50 hours per month to tasks like managing a family member’s home and assisting with doctor’s appointments. Caregivers typically spend $150 a month of their own money on the care recipient but many spend much more.

Chaiwoo Lee of MIT’s AgeLab said that it will become increasingly important to support caregivers, because the U.S. population is aging so rapidly.

“We’re all going to be doing this in the future, and we need to get ready for it,” she said.

Squared Away writer Kim Blanton invites you to follow us on Twitter @SquaredAwayBC. To stay current on our blog, please join our free email list. You’ll receive just one email each week – with links to the two new posts for that week – when you sign up here. This blog is supported by the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Comments are closed.

Why is child care deductible but caring giving isn’t?

If nothing is done, care givers will be fewer and fewer with more elderly left alone to fend for themselves on our streets.

My mother died “in her own bed” (as was her wish) from her third bout with breast cancer, about a month after her final diagnosis.

Our province (Ontario) provides home healthcare assistance from roughly 9am to 5 pm during weekdays.

So, our family had to make arrangements for her 2 sons and 1 son-in-law to provide assistance to her through the night on weekdays as well as 24 hour care though the weekends.

Her cancer specialist physician came to examine her at home about once a week.

It was a strain on the 3 of us; but one we willingly bore.

I found the many conversations we had before she lost consciousness to be very special with memories of her discussions of family from years ago being especially special.

Yes, the demands on the three of us were considerable; but, I don’t think any of us regretted the demands on our time.

What could / would we have done if there were fewer of us to share in the home healthcare duties? Or, if her final illness had been more prolonged? We don’t know because we were not put to the test.

But, given the weekday daytime home healthcare provided by the province and the willingness of her cancer specialist doctor to visit her at home periodically, we were able to give my mother the end of life home healthcare she wanted.

This is a critical piece of the health care system that badly needs fixing. With families now geographically spread it becomes even harder. We need to put more effort into home health care and less into high tech that benefits a very few.

Yes, caregiving places the most strain on low-income families.