Changing Tax Incentives for Retirement Saving Won’t Do Much Good

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Expanding Auto-IRAs and the Saver’s Credit is the real way to increase saving.

I just reviewed a manuscript where once again the authors proposed changing the tax incentive for retirement saving from a deduction to a credit. I used to push this idea myself, but now think it’s a diversion that could increase the revenue loss to the Treasury and would do little to increase saving. Let’s put it to rest.

A little background. Retirement saving under current law is tax advantaged. Employers and individuals take an immediate deduction for contributions to traditional retirement plans and participants pay no tax on investment returns until benefits are paid out in retirement. The favorable tax treatment significantly reduces the lifetime taxes of those who receive part of their compensation in contributions to retirement plans relative to those who receive all their earnings in cash wages.

The favorable treatment accorded retirement plans costs the Treasury the difference between the present value of revenue foregone and the present value of future taxes for activities undertaken in a given year. The Treasury’s estimate for 2021 was $187 billion, with about two-thirds attributable to 401(k)-type plans. Those are big numbers.

These tax incentives have two problems. First, they give the biggest reward to high earners. If a single earner in the top income tax bracket contributes $1,000, he saves $370 in taxes. For a single earner in the 12-percent tax bracket, that $1,000 deduction is worth only $120. It really doesn’t make sense to have the size of the incentive depend on earnings.

Second, it’s not clear that tax incentives actually encourage people to save more. A study of Danish data found that about 85 percent of people are “passive” savers who pay little attention to tax incentives. Only 15 percent are “active” savers who respond to tax subsidies; but they shift their money across accounts rather than increase their total saving.

In response to these issues, many policy experts have suggested replacing the deduction with a refundable credit. The Biden campaign suggested that a 26-percent tax credit would be revenue neutral and would encourage more low-wage workers to save. I’m no longer persuaded that either conclusion is correct.

In terms of cost, the deduction-to-credit proposal sounds like it simply transfers some of the tax expenditure from high earners to low earners. On closer examination, however, it could lead to more revenue loss if high earners put all their new saving in Roth 401(k)s/IRAs, which are unaffected by the proposal. That is, high earners would enjoy the same tax benefits as they do now, and the tax expenditure for low earners would increase. In short, while a credit would almost certainly be the way to structure a savings incentive if the country were starting from scratch, such a change – given the existing retirement infrastructure – could cost the Treasury more money.

More importantly, the shift from a deduction to a credit would do little to encourage the saving of low-wage workers. Low-earners who do not participate in a 401(k) plan when offered one are only a tiny part of the retirement saving problem, and most could be swept into the plans by auto-enrollment.

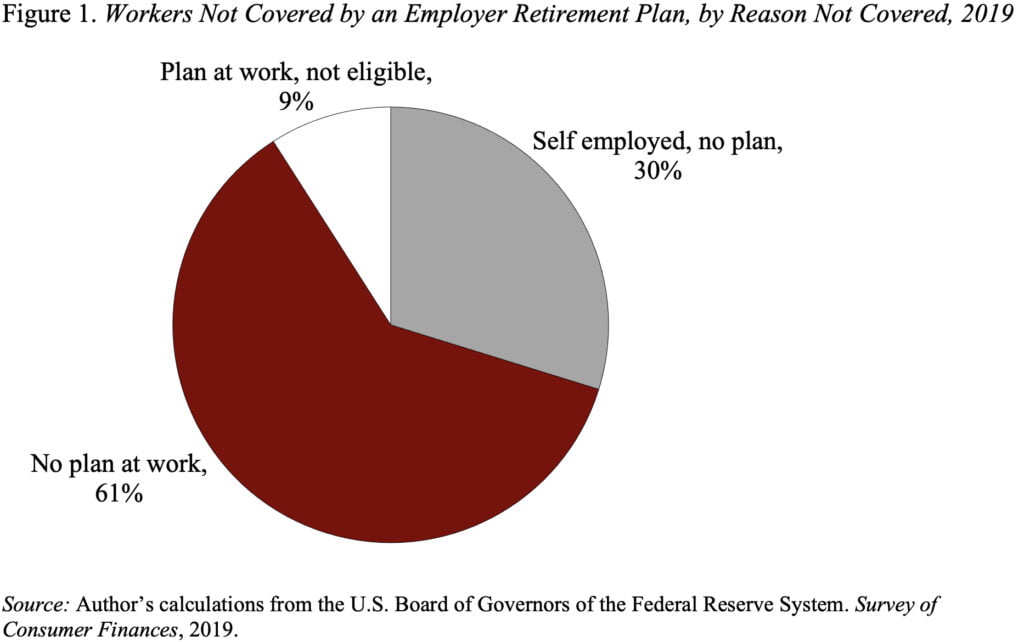

The real challenge is that most low and moderate earners are not covered by a plan at work (see Figure 1). This lack of coverage is currently being addressed in some states through auto-IRA initiatives, whereby employers without a plan must auto-enroll their employees in an IRA. We need federal legislation to make auto-IRAs universal.

(Interestingly, since Roth IRAs are the default in auto-IRA programs and, as noted, Roths are unaffected by the deduction-to-credit proposal, low earners participating in these programs would not benefit at all from such a shift.)

In addition to expanding coverage for low and moderate earners, we need to increase their saving by expanding the Saver’s Credit and making it refundable. The Saver’s Credit targets precisely the group that needs help and could be employed in conjunction with Roth IRAs in the state auto-IRA programs. SECURE 2.0 takes baby steps to expand the Saver’s Credit but does not contemplate making it refundable.

In short, universal IRAs along with an expanded/refundable Saver’s Credit is the way to increase the saving of low earners – not fiddling with the tax code.